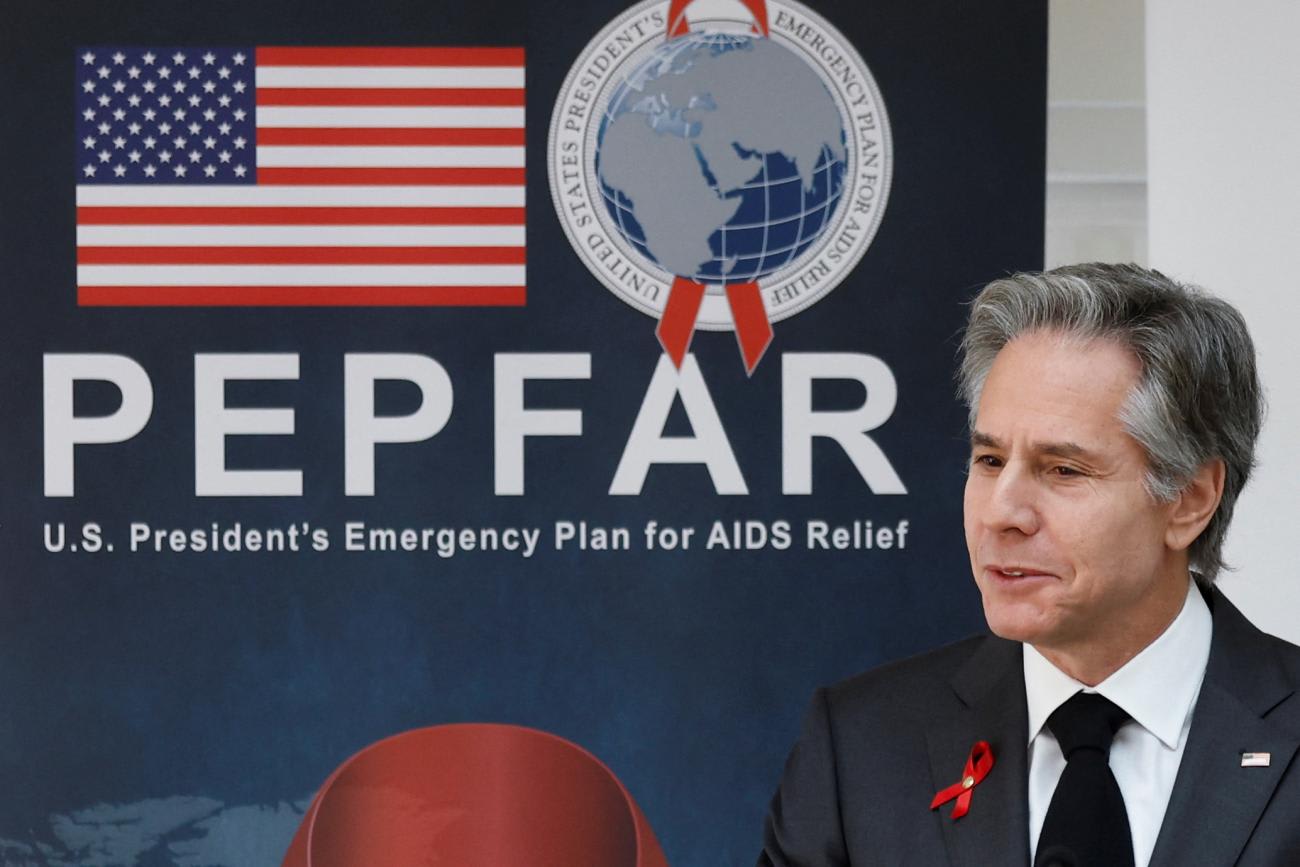

Five years ago, for the fifteenth anniversary of the President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), I opined that PEPFAR's impact on the HIV/AIDS pandemic "places it in the pantheon of iconic U.S. policy efforts, such as the Marshall Plan and the Apollo space program."

PEPFAR's success and stature help explain why, on the cusp of PEPFAR's twentieth anniversary, the Joe Biden administration has formulated the President's Emergency Plan for Adaptation and Resilience (PREPARE) for a different global health crisis—climate change.

PREPARE is, however, unlikely to enter the U.S. policy pantheon. None of the factors associated with PEPFAR's achievements are present in the nascent U.S. foreign policy efforts on climate change adaptation. Adaptation is a different policy beast from HIV/AIDS, which limits how much PEPFAR can inform actions against the health dangers that climate change threatens to create around the world now and into the rest of this century and beyond.

The Power of PEPFAR-ism

In launching PREPARE in November 2021 and issuing the PREPARE Action Plan in September 2022, the Biden administration connected the plan with PEPFAR. The administration called this initiative on climate change adaptation a "president's emergency plan" to mirror the PEPFAR moniker. The administration stated that PREPARE "is the largest U.S. commitment ever made to reduce climate impacts on those most vulnerable to climate change worldwide"—language that mimics the description of PEPFAR as "the largest commitment by any nation to address a single disease in history." The administration pledged to obtain from Congress $3 billion annually for adaptation finance, an amount that recalls the $3 billion proposed annually for HIV/AIDS efforts by former President George W. Bush in his January 2003 State of the Union Address.

The administration called the PREPARE initiative on climate change adaptation a "president's emergency plan" to mirror the PEPFAR moniker

The choice to draw from PEPFAR in constructing a U.S. strategy for adaptation has merit given that climate change, like the HIV/AIDS pandemic in the early twenty-first century, produces severe global health challenges for which low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) are unprepared. The PREPARE Action Plan states that climate change "threatens human health by worsening social and environmental determinants of health, imperiling access to and delivery of health care, increasing the potential for novel threats to emerge, widening inequality, and creating population-scale health risks."

In addition, no other U.S. global health effort compares to PEPFAR's success. COVID-19 demonstrated that foreign policy action on global health security failed to prepare the United States for a pandemic, with tragic consequences at home and abroad. The U.S. government has never sustained serious interest in the pandemic of noncommunicable diseases in LMICs or consistently thrown its weight behind other prominent global health objectives, such as the human right to health or universal health coverage. Prior U.S. foreign policy on climate change offered nothing to inspire a transformative strategy on adaptation.

The Problem with PEPFAR-ism

Although understandable, linking PEPFAR with a strategy on climate change adaptation raises difficult questions. The linkage highlights an endemic problem with U.S. global health engagement also witnessed with COVID-19—the failure to act decisively before health threats become dangerous emergencies. PEPFAR's accomplishments distract from the reality that—despite warnings about the trajectory of the global HIV/AIDS crisis—this emergency plan came after HIV/AIDS had become one of humanity's worst pandemics and a global development and humanitarian tragedy.

Likewise, PREPARE appears after the climate crisis has, despite warnings about the trajectory of global warming, become—according to National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan's foreword to the PREPARE Action Plan—"existential" in producing "sea level rise, unpredictable rainfall, flooding, drought, heatwaves and heat extremes, forest fires, and melting glaciers and permafrost" that "will undermine development gains, exacerbate geopolitical tensions, accelerate the food security crisis, and result in greater instability and humanitarian need." Concerning climate change, U.S. policymakers have not learned the brutal lessons about why emergency action on HIV/AIDS was needed.

Unprepared for PREPARE

If PREPARE repeats the same fundamental policy mistake that led to PEPFAR, can it replicate the impact that PEPFAR has had? PEPFAR's success reflects many things, but the proximate cause of its achievements has been twenty years of sustained political support and meaningful funding by the U.S. government. How the stars aligned to produce and maintain this commitment over decades is an incredible story, especially given that, prior to PEPFAR, global health was not a prominent U.S. foreign policy issue.

However, the story concerning climate change over the same decades is completely different. U.S. domestic and foreign policies on climate change have whipsawed incoherently across four presidential administrations, with adaptation receiving far less attention than mitigation in this hot mess. There is simply no evidence that climate change has produced or—for the foreseeable future—can generate the kind of political and financial support that allows PEPFAR's twentieth anniversary to be celebratory.

Further, the climate adaptation story in U.S. politics will develop very differently than the tale of PEPFAR. When PEPFAR was announced in 2003, antiretrovirals had already transformed HIV/AIDS in the United States from a death sentence to a manageable condition. In 2023, the United States is unprepared domestically for climate change and the divisive, disruptive, and expensive adaptations that will be necessary in the decades ahead. As COVID-19 demonstrated, a crisis at home takes political and financial precedence over the same crisis happening abroad.

For as far as the eye can see, the political stars for PREPARE do not align in any PEPFAR-esque way. Worse, the ongoing acceleration of the adverse consequences of global warming means that pressure to spend more economic resources on adaptation within the United States will amplify scrutiny of, and skepticism about, foreign aid for adaptation.

The Peril for PEPFAR

HIV/AIDS produced an emergency initiative. COVID-19 required emergency strategies. Climate adaptation now has an emergency plan. The infamous "crisis-and-complacency" pattern in U.S. approaches to global health threats increasingly looks like a "crisis-and-crisis-and-crisis" problem that hangs over PEPFAR on its twentieth birthday.

The lack of pandemic readiness that COVID-19 exposed set back global efforts against HIV/AIDS. The pandemic highlighted that these efforts did little to support pandemic preparedness and response concerning other diseases, which produced policy pivots in that direction.

The lack of preparation for climate adaptation creates similar dangers for PEPFAR and kindred programs. Synergies between PEPFAR's activities and addressing adaptation needs are not obvious, limiting the potential for pivots to contribute to handling the adaptation crisis.

In this context, sustaining support and protecting funding for HIV/AIDS will become more difficult as metastasizing adaptation threats at home and abroad escalate demands for increasingly scarce political capital and economic resources. And there is unlikely to be an emergency plan to respond to that emergency.