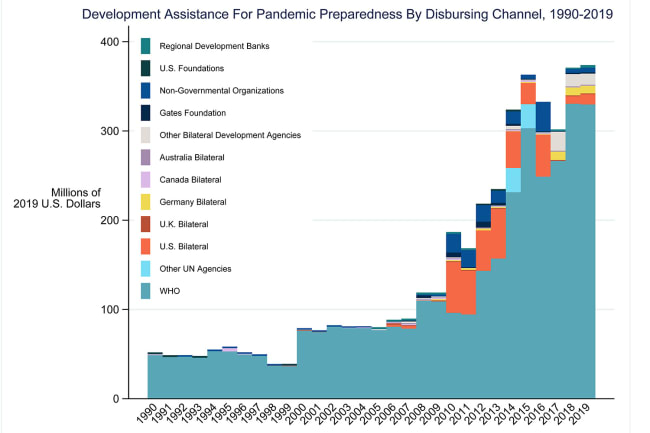

In 2020, a deadly respiratory disease swept the globe and caused an upsurge in deaths on multiple continents. I am referring to tuberculosis (TB), not COVID-19. The disruption caused by COVID-19 produced an increase in global TB deaths for the first time after two decades of hard-won progress against the world's leading pre-pandemic infectious disease killer. COVID-19 has also turned back the clock on progress in low- and middle-income countries against HIV/AIDS and malaria—two of the world's deadliest diseases.

However, COVID-19's impact on these diseases reinforces the importance of the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria (Global Fund). The Global Fund is a multistakeholder mechanism established in 2001 that became the largest multilateral global health funder pre-COVID. COVID-19 revealed the pandemic preparedness and response capabilities that the Global Fund possesses. As the United States prepares to host a replenishment conference for the Global Fund in September, understanding the fund's performance before and during the pandemic highlights why sustaining and strengthening it are critical for U.S. global health policy and leadership.

The Global Fund Pivots Against a New Pandemic

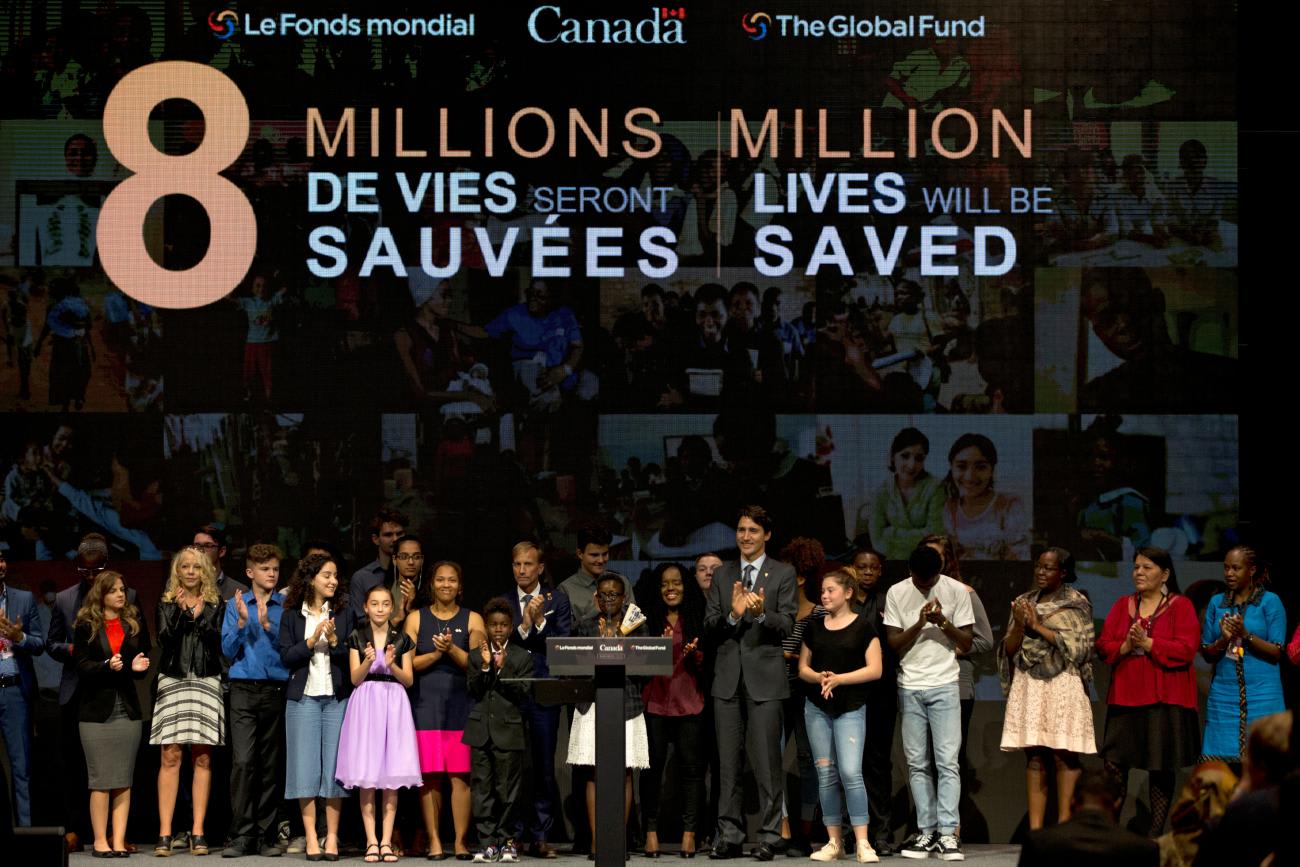

Before COVID-19, the Global Fund played a seminal role in efforts to reduce the global burden of disease associated with HIV/AIDS, TB, and malaria—with its partners in over 125 countries receiving nearly $53 billion in dispersed investments and saving an estimated 44 million lives from 2002 to 2021. This record explains why countries turned to the fund when a new pandemic emerged and how the fund supported the fight against this emergency.

The Global Fund, with its partners, saved an estimated 44 million lives from 2001 to 2021

The Global Fund responded to country-led requests by creating its COVID-19 Response Mechanism. The mechanism shored up HIV/AIDS, TB, and malaria programs, strengthened health systems in crisis, and supported pandemic countermeasures. In 2021, Congress invested $3.5 billion in this special, expedited effort, which represented a large portion of the funding the American Rescue Plan Act allocated to international COVID-19 responses.

The Global Fund has played a major role in most non-vaccine aspects of the global COVID-19 response. In many low- and middle-income countries, it has been the top financial supporter for tests, therapeutics, and personal protective equipment. It has coordinating roles in the Access to COVID-19 Tools Accelerator (ACT-A), the global partnership to expand availability of pandemic technologies worldwide. The fund co-leads three of ACT-A's four pillars, helping to spearhead efforts on diagnostics, therapeutics, and health systems strengthening.

In the health systems pillar, the Global Fund shares coordination responsibilities with the World Bank. However, the bank has proven slow and ineffective in deploying financial resources to bolster countries' health systems in the pandemic. Although the bank has allocated $20 billion for COVID-19 tools and health systems strengthening, only $5.8 billion had been approved for rollout two years into the pandemic, while 71 percent of the funding remained unused.

An independent review of ACT-A pinpointed the reasons. In many low- and middle-income countries, "governments with high debt levels were reluctant to contract more debt to fund their COVID-19 response," especially when the World Bank's inflexible funding procedures were ill-suited for the immediate, fast-changing needs of pandemic response. In contrast, the Global Fund was able to rapidly disperse actionable resources that did not increase national debt burdens.

The Global Fund's Comparative Advantages

The challenges created by COVID-19 highlight the Global Fund's comparative governance and operational strengths in pandemic preparedness and response. The fund has built up trust through decades of collaboration with implementing countries. It can move money quickly and accountably. It has experience investing in supply chains, community health workers, and other components of health system strengthening.

The Global Fund also innovated with implementing partners to sustain and expand their activities amid COVID-19. For example, as frequent trips to doctors and pharmacies became not just inconvenient but dangerous during the pandemic, clinics in several countries–including Nigeria, Mozambique, South Africa, Tanzania, Zambia, and Zimbabwe—dispensed months of HIV/AIDS and TB medications. Caregivers also increased digital and home-based care, while testing programs screened simultaneously for TB and COVID-19. Many of these crisis adaptations have become advances the Global Fund and its partners will continue.

Reality Check

Even with the strengths of the Global Fund demonstrated during COVID-19, the pandemic has damaged the battles against HIV/AIDS, TB, and malaria. In 2020, global TB deaths increased, and TB treatment dropped, with a 15 percent decrease in treatment for drug-resistant infections worldwide. Expansion of HIV treatment similarly faltered, with the number of patients on treatment growing in 2021 at the slowest rate since 2009. Lastly, the World Health Organization and Global Fund have documented how progress against malaria has stalled, particularly for target groups like pregnant mothers receiving preventive malaria therapy.

Rebounding through Replenishment and Reflection

To recover from COVID-19's impact, the Global Fund has requested a 30 percent increase in commitments for a total target of $18 billion during its 2023–2025 funding cycle. This level of funding will make it possible to achieve the services, medical tools, infrastructure, and health workforce needed on a path to end HIV/AIDS, TB, and malaria as pandemics.

In 2020, global TB deaths increased, and TB treatment dropped, with a 15 percent decrease in treatment for drug-resistant infections worldwide

In the United States, the Joe Biden administration has pledged $6 billion of this total and will host the Global Fund's replenishment conference in September. With U.S. law capping American contributions at 33 percent of the Global Fund's budget, other donors need to pledge $12 billion to unlock the United States' full $6 billion commitment.

Rebounding from COVID-19 will also require reflection to learn from pandemic responses and strengthen the Global Fund going forward. For example, the Global Fund needed to direct funding to meet the demands of COVID-19 while continuing to prioritize human rights, such as access to care and legal services for marginalized groups. The Global Fund is designed to have effective programs that achieve equity for neglected and stigmatized populations, notably groups most vulnerable to HIV/AIDS. Balancing these demands remains crucial for both COVID-19 and future pandemics.

The pandemic also demonstrated the benefits of the Global Fund's multistakeholder model, as the recent independent report of the Multilateral Organisation Performance Assessment Network found. Global health is a crowded space with many public institutions and nongovernmental actors seeking to collaborate. The Global Fund spreads decision-making power through seats on its governing board for donor countries, recipient countries, foundations, companies, civil society, and communities living with the three diseases. Global Fund grant proposals and implementation require a multistakeholder governance committee at the country level. The Global Fund can improve by further facilitating the agency of implementing countries, including their civil society and governments. As seen during COVID-19, the Global Fund's governance model builds relationships and trust that are invaluable when countries must rapidly respond to new pandemics.

Other efforts to strengthen pandemic preparedness and response should emulate this model, including the new financial intermediary fund (FIF) at the World Bank. The FIF will pool and disburse resources for countering pandemics. The FIF's relationship to the Global Fund—and whether the Global Fund will be a major conduit of its funding—is not yet clear.

As the Biden administration and other stakeholders negotiate the FIF's details, the Global Fund's experience suggests a successful FIF requires input from, and decision-making power for, the governments and civil society of implementing countries, not just episodic consultation with donors. Both the ethics of "decolonizing" aid and efficacy in facing new health security threats demand it.

What the Global Fund Teaches U.S. Foreign Policy

The Global Fund's experience also teaches other lessons for U.S. foreign policy and global leadership. On pandemics, the Global Fund's investment in health systems—from labs to community health workers—tackles HIV/AIDS, TB, and malaria and increases preparedness for future health threats. Such strategic investments can avert human and economic costs by simultaneously delivering results for today while building capacity for future pandemics.

Similarly, the Global Fund demonstrates the wisdom of investing in agile, multistakeholder institutions through consistent U.S. financial contributions. The legal cap on the U.S. share of commitments to the Global Fund has propelled two decades of burden-sharing and shows that U.S. contributions can and should be structured to encourage other nations of every income level to invest in public goods.

COVID-19 has strained efforts to control HIV/AIDS, TB, and malaria. But the pandemic reminds us of what is at stake, and how the United States can rally partners to confront infectious diseases and other global challenges—including climate change or authoritarian aggression. Commitments to effective multilateralism, the voice and agency of affected countries and populations, and the scaling up of proven assets are fundamental.