On March 17, Tanzanian President John Magufuli died after a protracted hospitalization for what many speculated was a case of COVID-19, a disease he had long denied existed in Tanzania.

Nearly a year ago, a colleague and friend of mine in Tanzania sent me a message: "Yesterday, our president said that the hospitals are empty, and there are no more COVID-19 patients," continuing, "He was silent on the number of deaths." A month earlier, the government had stopped reporting data on COVID-19, despite reports of epidemics in neighboring countries including Kenya and Uganda, and travelers from Tanzania who had tested positive for COVID-19 abroad. My friend was concerned that the government was lying to the public. However, like many people in Tanzania, she was afraid to speak publicly about her opinions and concerns for fear of retaliation.

Afraid to speak publicly about her opinions and concerns for fear of retaliation

When leaders deny and downplay the danger of COVID-19, including in the United States, people die. Magufuli downplayed the impact of the virus in his country for most of the pandemic. He dismissed the value of vaccines, called them dangerous, and promoted untested treatments including steam inhalations and herbal cures.

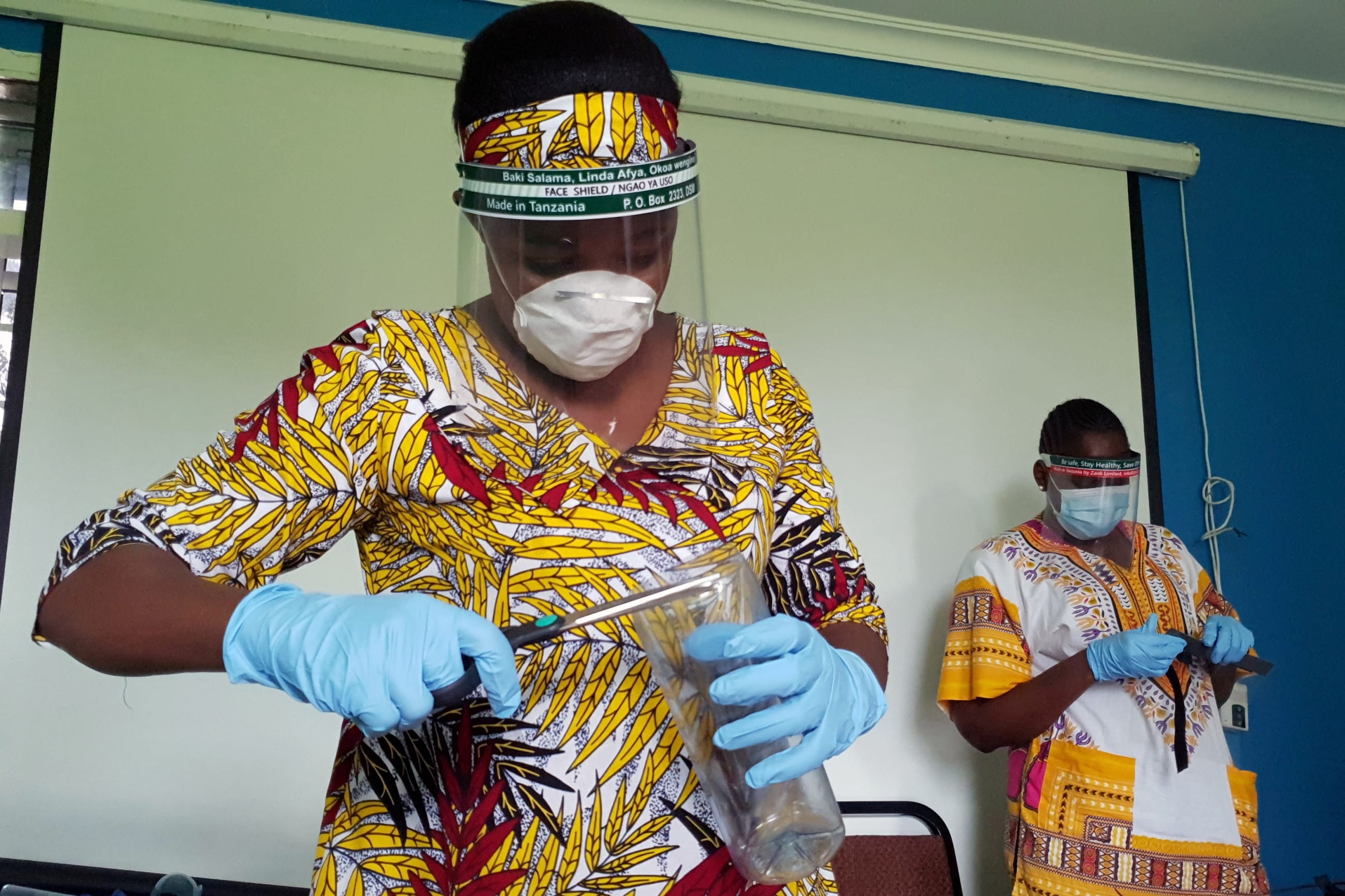

For months, the government's failure to address COVID-19 forced citizens to choose whether to believe their leaders or whistleblowers, and effectively left it to individuals to curb the epidemic. Tanzanians are doing what they can to protect their families and friends, but it is extremely difficult when there are no public health mandates or clear guidance. For example, my friend and her family are making their own face masks and wearing them even when others do not.

COVID-19 testing is unavailable for most of the population, but there is good reason to believe that the death toll is mounting in Tanzania. Over the past two months, my friend has shared stories of family and friends who died from suspected COVID-19 infection, just as a former minister and Member of Parliament Mark Mwandosya has been sharing obituaries of friends and family members who have died after experiencing COVID-19 related symptoms. Organizations in Tanzania, such as the Catholic Church have reported an increase in funerals, although they can't prove that these deaths were caused by COVID-19. And Magufuli's death, if it proves to be a consequence of COVID-19, would be the starkest reminder of all.

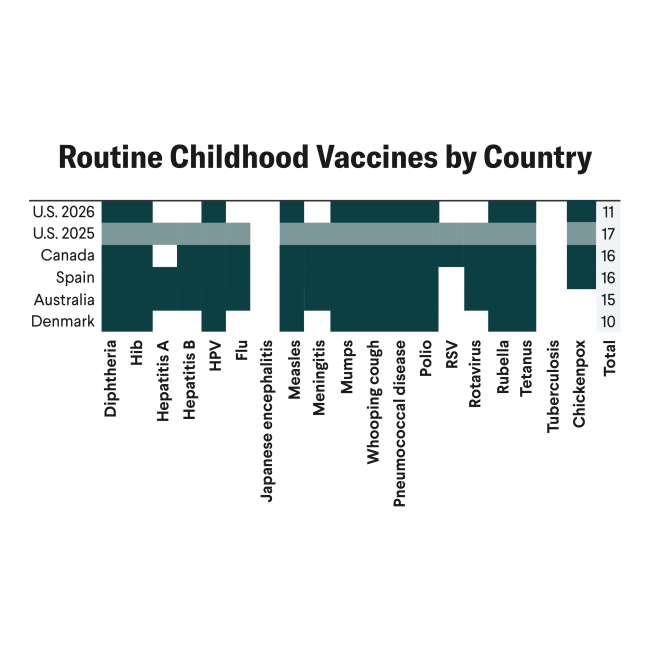

Only in February of this year, after the World Health Organization and several organizations in Tanzania urged the government to implement public health measures to curb the spread of the virus, did the late president finally admit that the country had a COVID-19 problem. But merely acknowledging the presence of the disease is insufficient. To curb its spread and save lives, Magufuli's successor needs to embrace important public health measures including collecting and sharing timely and accurate data, communicating evidence-based health messages clearly and consistently, and limiting the spread of misinformation — and of course, promoting the use of vaccines.

Misinformation is communicated more clearly than the advice about the pandemic

Misinformation about COVID-19 continues to drown out the government's meager recommendation, as people who have lived in fear and confusion for months search for prevention and treatments. For example, my friend forwarded me an advertisement shared in Tanzania that claims that bee stings increase immunity — a claim people have also made in other countries including Germany, China, and Brazil. According to the video, a COVID-19 patient should receive five bee stings a day. "Unbelievable. And this on TV," my friend wrote.

Sadly, this misinformation is communicated more clearly than the advice about the pandemic that most Tanzanians have received from their own government. The government has not given people the information they need to choose how to protect themselves, and many individuals may lack a clear understanding of the disease's seriousness. Without accurate information about COVID-19 and ways to prevent it, misinformation will continue to cause avoidable illness and deaths.

Upon the announcement of Magufuli's death, my friend sent me a message: "We waited two weeks for an announcement. We need the vaccines." She hopes that this national tragedy will finally force Tanzania's leaders to acknowledge the seriousness of the pandemic, and push the government to enforce measures such as mask-wearing and social distancing, to publicly share accurate data on the number of COVID-19 cases and deaths in the country, and to distribute vaccines. Only these public health measures can help to curb the spread of misinformation and the virus, and save lives.