After a decade of deliberation, Indonesia's tax on sugar-sweetened beverages (SSB) remains in limbo as state regulators waffle on whether to launch the levy in the near future.

During a coordination meeting with the House of Representatives on December 8, 2025, Indonesia Finance Minister Purbaya Yudhi Sadewa postponed a SSB tax that was to be implemented in 2026, citing the country's economic condition. Enactment had advanced far enough to include the SSB tax in this year's state budget, with a targeted revenue of 7 trillion Indonesian rupiah ($420 million).

"When the domestic economy has improved and grown by 6%, I promise to come to the House of Representatives to present on the SSB tax," said Sadewa. This announcement follows a deferral in June 2025, when a presidential regulation governing the tax was not issued, preventing the Ministry of Finance from proceeding with a deployment plan.

Public health advocates warn that any further delay could increase the health burden due to the connection between SSB consumption and noncommunicable diseases (NCDs). Several studies have examined how SSB consumption raises the risk of NCDs such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and chronic kidney disease. A 2025 burden-of-proof study suggested that higher intake—even a single serving—can elevate the risk of developing type 2 diabetes and ischemic heart disease.

Over the past 20 years, Indonesia has witnessed a 15-fold increase in SSB consumption

"The government's decision to once again postpone the excise tax on sugary drinks in relation to the 6% economic growth target is very unfortunate," said Nida Adzilah Auliani, project lead for food policy at the Center for Indonesia's Strategic Development Initiatives (CISDI). Hitting this target could prove difficult given that Indonesia's annual growth has been 5% or less since 2014, according to World Bank figures.

Over the past 20 years, Indonesia has witnessed a 15-fold increase [PDF] in SSB consumption. A 2018 survey by the country's Ministry of Health shows that 61% of the population (ages 3 years and older) drinks these beverages at least once a day. A 2024 modeling study by CISDI predicts that the tax could avert 3 million new cases of diabetes and 455,000 deaths over a decade.

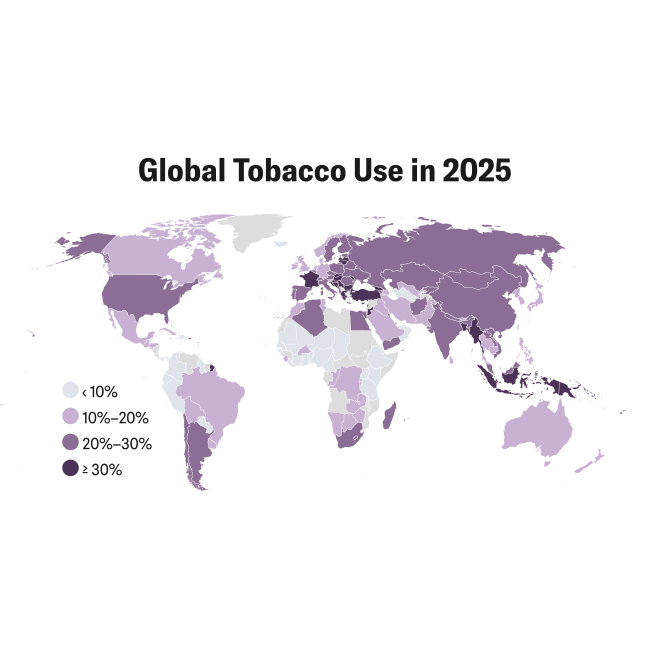

"Besides the health benefits, a SSB tax is a great opportunity for Indonesia to bring in more revenues," said Muhammad Zulfiqar Firdaus, the study's lead author and CISDI's health-economics research associate. The excise tax on SSBs could ease Indonesia's reliance on taxes from the tobacco industry, which stood at 211.7 trillion rupiah ($12.7 billion) in 2025 and composed approximately 8% of the total government revenue.

Indonesia's Path to a Sugary-Beverage Tax

In 2015, the World Health Organization (WHO) concluded, after conducting a systematic review, that "there is reasonable and increasing evidence that appropriately designed taxes on sugar sweetened beverages would result in proportional reductions in consumption, especially if aimed at raising the retail price by 20% or more."

The following year, Indonesian officials began discussing excise taxes on sugary drinks, following encouragement from the WHO and growing concerns about the prevalence of NCDs.

In 2020, the Ministry of Finance and the Ministry of Health conducted a feasibility analysis of the excise tax and submitted a proposal to Commission XI of the Indonesian House of Representatives, which has oversight of economic and financial development.

By 2022, the finance ministry planned to launch the SSB tax with a revenue target of 1.5 trillion rupiah ($90 million) for that year, but officials decided to defer, citing the need for economic recovery from the pandemic. The tax plan resurfaced in 2023, aiming this time for 3.08 trillion rupiah ($184 million) in revenue, but was waylaid once more for another year.

"Timeline-wise, the SSB tax has been included in the state revenue and expenditure budget plan (RAPBN) every year since 2022, each with a bigger projected revenue from the previous year," explained Auliani.

So far, the government has not publicly disclosed a specific tax rate for the SSB tax, but according to CISDI's policy brief, the guideline would be a 20% increase on these beverages' prices based on the results of similar policies in 49 other countries.

In November, Febrio N. Kacaribu, the finance ministry's director general of fiscal and economic policy, said that Indonesia would consider existing SSB taxes in seven Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) countries: Brunei, Cambodia, Laos, Malaysia, Philippines, Thailand, and Timor Leste. He said that the average SSB tax on those countries is 1,771 rupiah per liter ($0.10).

Currently, Indonesia has three excised goods: tobacco products, ethyl alcohol, and beverages that contain ethyl alcohol. As with tobacco, the SSB tax has faced resistance from industry associations, such as Indonesia's Food and Beverages Producers' Association (GAPMMI) and the Soft Drink Industry Association (Asrim).

Asrim chairman Triyono Prijosoesilo has stated that his organization believes the proposed SSB tax is untimely.

"Timeline-wise, the Fast-Moving Consumer Goods (FMCG) industry, including the beverage industry, is still struggling," said Prijosoesilo on December 13. He added that the industry's growth rate up to the third quarter of 2025 had only reached 1.8%. "Other ready-to-drink beverage categories are still experiencing negative growth up to the third quarter, so postponing the SSBs tax is appropriate," he said.

Salsabil Rifqi Qatrunnada, a quantitative research officer at CISDI, said this argument against the SSB taxes echoes what tobacco industry executives say about levies.

"We have looked at other countries and found no research that shows mass layoffs or unemployment from implementing SSB taxes," Qatrunnada said.

Prijosoesilo thinks the SSB tax is inappropriate for managing the risk of NCDs, citing a 2015 study showing that SSBs only contribute 6.5% of the total calorie consumption of the Indonesian population.

Countries such as Mexico and South Africa witnessed reductions in SSB sales following the implementation of taxes. A 2024 study examined how consumer purchases of the beverages changed following levies in five U.S. cities: Boulder, Colorado; Philadelphia; Oakland, California; San Francisco; and Seattle, Washington. The study found that a 33.1% increase in SSB prices reduced purchase volume by 33%, on average.

"We also found that consumption declines and price increases have remained at these lower levels of consumption and higher prices up to two years after implementation," said Scott Kaplan, the study's corresponding author and an assistant professor at the U.S. Naval Academy's Department of Economics.

To further limit SSB consumption, Auliani said Indonesia should also pursue other policies such as adding front-of-package labeling (FOPL) on processed food and advertising restrictions for products high in fat, sugar, and salt.