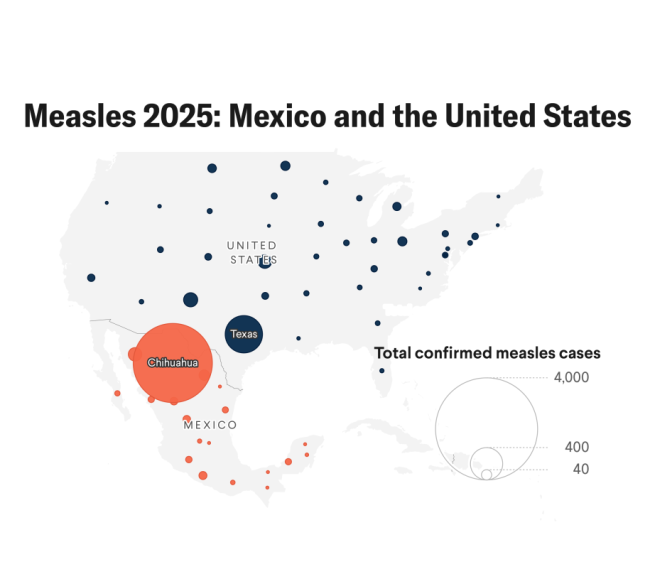

During the last week of January, South Carolina's measles emergency became the largest regional outbreak on record since the United States eliminated the disease in 2000. The outbreak has sickened 876 people since sparking in October 2025, surpassing last year's surge in West Texas. Ninety percent of the cases have involved unvaccinated individuals, and 19 adults and children have been hospitalized for complications of the disease. As of Tuesday, 354 people are in quarantine, and 22 are in isolation.

With measles infections at their highest levels in three decades, physicians and educators in South Carolina are scrambling to contain the virus and navigate dropping vaccination rates.

"For a lot of physicians, there's a lot of anticipation and worry about, 'will I have a case come in front of me, and how will I recognize it, and how will I respond in the best way to provide the best care possible to that child and family?,'" said Stephen Thacker, a pediatrician at the Medical University of South Carolina.

Measles containment faces significant challenges nationwide and in Spartanburg County, the state's measles epicenter, as more people claim religious and medical exemptions to bypass state requirements for school vaccination. For measles, when vaccination rates fall below 92% to 94%, a community is no longer protected by herd immunity. This collective shield protects the health and well-being of those who cannot get the vaccine, such as pregnant people, or those who may have allergies.

I've had five cases of measles that I've treated, and they've all been different

Stuart Simko, pediatrician at Prisma Health in Greer

"Fifty percent of [pregnant] women that get measles in the first trimester will not have a good outcome," said Helmut Albrecht, an infectious disease physician at Prisma Health, a nonprofit health organization based in South Carolina.

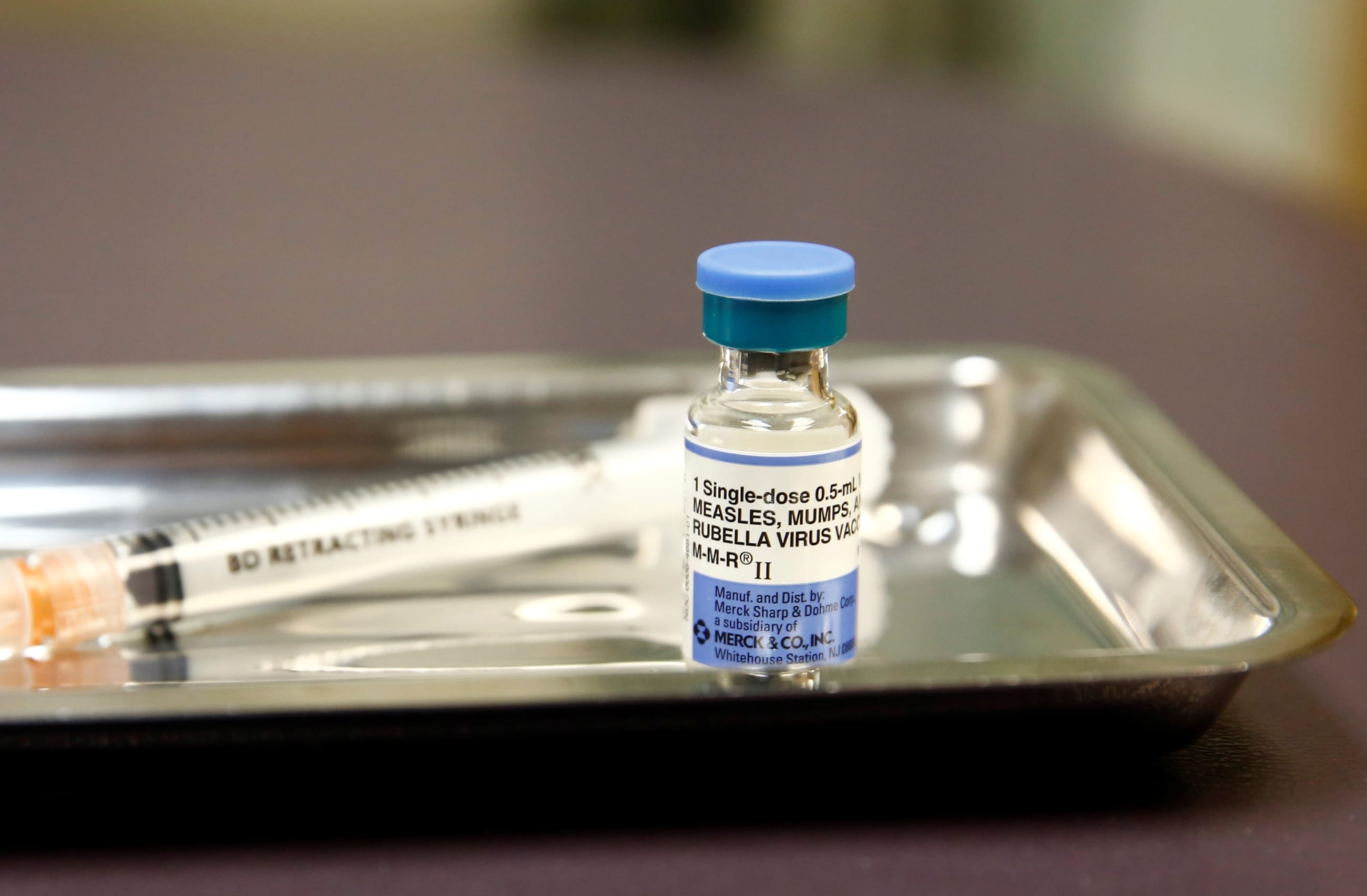

The outbreak has spread primarily through elementary and secondary schools with large communities of students who have not received the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine. Among U.S. states and Washington, DC, South Carolina's kindergarteners rank in the middle—twenty-seventh—for MMR vaccination coverage. But Spartanburg's school immunization rates have fallen since the COVID pandemic and sit at 88% for the 2025–26 school year. About 1 in 10 students now claims a religious exemption.

Linda Bell, South Carolina's state epidemiologist and the incident commander for the measles outbreak from the South Carolina Department of Public Health (DPH), said that in Spartanburg, there are likely a few thousand children and adults who remain unvaccinated against measles.

According to other clinicians in the state, people are not getting vaccinated for a range of social, political, and access-related reasons. Some families are "reacting to COVID vaccine mandates and social media backlash" and "are still very angry about COVID-related vaccine mandates and prolonged mandated school closures," said Martha Edwards, president of the South Carolina chapter of the American Academy of Pediatrics (SCAAP).

Spartanburg is also home to South Carolina's largest Ukrainian American community, where health-care providers have observed lower vaccination rates. Research on vaccine hesitancy in former Soviet Union countries links historical distrust of the Soviet government to skepticism of publicly-sponsored vaccine guidance.

Additionally, parents are also experiencing mistrust due to the disinformation and misinformation on vaccines amplified locally, statewide, and nationally, said Annie Andrews, a pediatrician based in Charleston. "But of course we've seen for quite some time the injection of partisan politics into public health," she added.

"It used to be common for people to vaccinate for everything but push back on MMR [vaccines] especially due to the Wakefield disinformation," said Edwards. In 1998, fraudulent research published by Andrew Wakefield falsely claimed a link between the MMR vaccine and the development of autism and inflammatory bowel disease. The Lancet retracted the paper in 2010 after the General Medical Council found Wakefield guilty of serious professional misconduct, and he lost his medical license.

In rural parts of Upstate South Carolina, families who lack a primary care physician or have one who does not stock the vaccines must often drive long distances to get their immunizations. "The health department does not have the staffing to keep up with appointments [in rural areas] that are scheduled for vaccine updates, especially at the onset of the school year," said Edwards.

Recognizing and Treating Measles for the First Time

Given that isolated outbreaks have occurred nationwide since measles was eliminated, many young physicians do not have hands-on experience with the disease, having only encountered descriptions in medical school textbooks or video lectures. Now, SCAAP and other organizations are gathering pediatricians across the state to work with the Department of Public Health on best practices for measles diagnosis, screening, triage, and support, said Edwards. Through webinars and monthly newsletters, they are ensuring that their community of clinicians has up-to-date information on the outbreak.

The early detection and diagnosis of measles is critical, both to quickly isolate contagious patients and to limit spread. The virus can remain airborne for up to two hours after an infected person leaves a room, meaning that an unmasked patient in an emergency department can expose many others.

While most people recover on their own, measles can cause severe illness, including pneumonia, acute or progressive brain inflammation (encephalitis), ear infections, and severe diarrhea. About 1 in 5 unvaccinated people in the United States who gets measles is hospitalized, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

"I've had five cases of measles that I've treated, and they've all been different," said Stuart Simko, MD, a pediatrician at Prisma Health in Greer, South Carolina. "They all have looked pretty sick, would be the best way to put it." South Carolina's health department and Prisma Health have withheld details about hospitalized patients' complications, citing privacy concerns.

According to the CDC, about 1 in every 20 children with measles will have pneumonia, the leading cause of death from measles. "Children have the risk of secondary bacterial infection, which can cause really severe pneumonia, some even requiring surgery," said Robin LaCroix, a pediatric infectious disease specialist who is currently treating children with measles in both Greenville and Spartanburg.

"We have lost our ability to contain this with the immunity that we have, so we need to revaccinate people," said Albrecht.

Adults concerned about their immunity can request an MMR titer—a blood test that checks for antibodies from vaccination or past infection. Those showing low or negative immunity should generally receive another vaccine dose, according to Andrews.

For unvaccinated individuals exposed to measles, time is critical. While isolation typically lasts 21 to 28 days, LaCroix noted that there's a narrow window for intervention.

"If we can identify that exposure within a short window, 72 hours, basically three days, we can give you an immunization," LaCroix said. "Your body will make its own defensive antibodies to protect you from this virus, and you can avoid quarantine."

Mohammed Al Gadban, a pediatrician based in Easley and the founder of Totality Pediatrics, mentioned that some families who previously refused the MMR vaccine have come in to get their children vaccinated due to the outbreak. "Parents are also willing to learn more about the vaccine and educate themselves about it," he said.

How Schools and Early Childhood Education Centers Are Responding

The South Carolina Department of Public Health has linked the outbreak to at least 17 schools, with student quarantines involving fewer than five students at some sites to 59 at Holly Springs-Motlow Elementary. The virus has also reached local colleges, with Anderson University reporting a case affecting 50 students on January 16 and Clemson University confirming a case that sent 34 students into quarantine on January 17.

"For a lot of parents in South Carolina, this feels like being dragged back into the worst days of COVID. There's real collective trauma around quarantine and remote learning—the strain of trying to make home function as a classroom, an office, and a hospital all at once. Kids struggle to stay focused on screens, technology fails, and teachers are stretched thin trying to teach students in the classroom and at home at the same time," Andrews said. "Families are paying the price for a crisis that was entirely preventable."

Greenville County School District, which includes more than 77,000 students across elementary, middle, and high schools in Upstate South Carolina, established checkpoints to catch cases early. The district requests that parents report student illnesses, and school nurses and staff are actively observing symptoms onsite to separate affected individuals, contact parents or emergency contacts for immediate pickup, and recommend that families consult a medical provider, said Tim Waller, director of media relations for Greenville County Schools. For students in quarantine, learning is facilitated through online learning platforms.

The Southern Alliance for Public Health Leadership (SAPHL) created a coalition of public health professionals, clinicians, and educators in Spartanburg in response to the measles outbreak to support education and vaccine outreach. They hope to engage school leaders in this local network who may be left out of the conversation, and build resources for preventing measles in early childhood environments.

"The biggest project we're working on right now is really to put communications materials and campaigns for early childhood education around measles and being prepared for measles, and helping them understand what the risks are. There are so many early childcare providers across the state, across the county, and there's not a single organization that represents them," said Scott Thorpe, the executive director of SAPHL.