Taming the pandemic will take three things: Access to COVID-19 vaccines that decrease susceptibility to infection, reduce transmissibility to others, and prevent progression to severe disease. Maintaining these three efficacies will require a new vision for global surveillance—a unified vision.

During the G7 summit in June, it was welcome news when leaders of major industrial nations announced "big steps" toward pandemic recovery by pledging 1 billion COVID-19 vaccine doses to low-income countries. This number adds to. the more than 3 billion doses already administered worldwide. But it won't address the unwelcome fact that humankind remains behind the curve of knowledge on emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants, including their biologic properties, geographic prevalence, and rates of spread. This information is critical in order to produce well-matched and disease-preventing COVID-19 vaccines.

"We remain behind the curve of knowledge on emerging COVID-19 variants"

We already have Alpha, Beta, Gamma, and Lambda "variants of concern" (VOC) and, more recently, a seemingly more threatening and transmissible Delta VOC. In contrast, we have incomplete and mixed reports on the efficacy of almost twenty COVID-19 vaccines authorized for use worldwide. The statistics range from greater than 90 percent for some (successes) to less than 50 percent for others (failures). Currently, less than a dozen countries sequence more than 10 percent of their known COVID-19 cases with full RNA genome coverage—a process that allows scientists to determine if the virus has mutated. The remaining countries sequence far less and the minimal percentage of cases and desirable quality of data that offer dependable knowledge has not been established. Logistics and laboratory bottlenecks can also often result in delays that range from weeks to months, leading to inadequate real-time tracking of any VOC. And whole genome sequencing alone provides only one aspect of the surveillance picture we need.

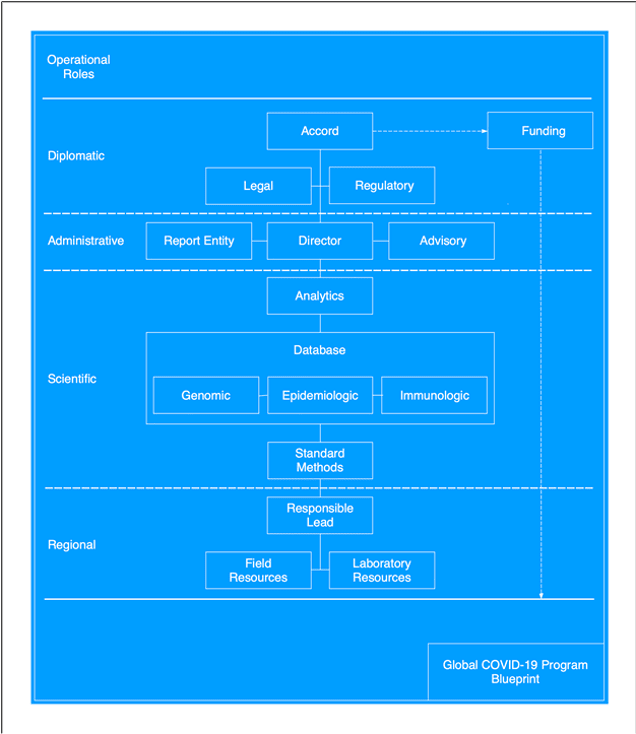

Below is outlined a provisional "blueprint" for a global COVID-19 surveillance program that could solve the problems keeping us one step behind beating this virus. The blueprint proposes four operational levels—diplomatic, administrative, scientific and regional— with each offering a concrete basis for debate, improvement, and implementation.

Diplomatic

Emergency executive and intergovernmental actions are essential in 2021. Participants in the upcoming October G20 summit in Italy and at November's virtual APEC forum in New Zealand could engage by addressing the following question: What are the opportunities, precedents, and challenges that pertain to the blueprint?

In December 2020, the President of the European Council, Charles Michel, proposed an "International Treaty on Pandemics" and in March 2021, 25 heads of government and international agencies aligned by signing a joint call for high-level political action.

"One diplomatic option to consider is the creation of a 'Virus Surveillance Accord'"

Another diplomatic option to consider is the creation of a "Virus Surveillance Accord" that aims to overcome the inherent limitations of the 2005 International Health Regulations (IHR) and unresolved issues of the 2007 World Health Assembly (WHA) on sample sharing, sample sovereignty, and intellectual property. Such an accord would apply during major outbreaks and pandemics and could be determined or triggered by the World Health Organization (WHO) Director-General. One way to proceed is by rapid and informal diplomatic consensus that organizes and provides for adequate funding of the establishment of a Global COVID-19 Program, which is subsequently followed by formal diplomatic agreements.

Ultimately, either the proposed "treaty" or "accord" could incorporate specific definitions and articles that establish legal and regulatory codes for strengthening mutually assured cooperation among 2005 IHR "states parties."

Administrative

Overarching responsibilities and accountabilities are essential features of the blueprint. So, the role of the director would be to foster mutual cooperation among partnering countries and thereby maintain surveillance and situational awareness worldwide. The role of a report entity would be to track the incidence, prevalence, and distribution of existing and emerging VOCs; to maintain evidence-based reports for partnering countries; and to identify potential targets for updating COVID-19 vaccines. The role of the multidisciplinary Advisory would be to provide guidance on scientific and technical topics and to offer independent assessments of capabilities, limitations, and needs of partnering countries.

Scientific

High quality, directly comparable, and representative data are essential deliverables of the blueprint. These programmatic goals will require standard methods for sample collection, laboratory testing, and data warehousing. They will also require that the program provides standardized immunologic laboratory reagents to partnering countries. A dedicated database can be created or adapted to organize and associate three categories of data and metadata:

- Epidemiologic—sample acquisition time, place, clinical condition

- Genomic—full viral sequences, Phred quality

- Immunologic—antibody typing, neutralization

At present, such a comprehensive database does not exist for SARS-CoV-2 or other pathogens. Computer-based analytics can offer two powerful capabilities. The first is the ability to visualize the spread and distribution of VOCs. The second is relating variant genomic sequences to their complex immunologic characteristics, which are required to identify and select threatening VOCs for next-generation COVID-19 vaccines.

"Governments, organizations, foundations, and academic centers could build and maintain global surveillance by fulfilling major roles"

Regional

Partnering with developed countries that maintain substantial infrastructures—such as national centers for disease control and related networks—are essential objectives of the blueprint. Also partnering with underdeveloped countries that have limited or nonexistent infrastructures are essential objectives. One or more Responsible Leads in each partnering country would oversee the operations pertaining to Field Resources (sample acquisition, storage and transport) and Laboratory Resources (sample processing and analyses). For countries and regions with lesser infrastructures, samples could go to those with greater infrastructures. The use of supply chain management tools would help to reduce logistic bottlenecks and increase decision making efficiencies.

Using such a blueprint, governments, organizations, foundations, and academic centers could build and maintain global surveillance by fulfilling major roles. Below are identified several opportunities with potential synergism.

All manufacturers of COVID-19 vaccines are facing unprecedented challenges regarding whether, when, and how to update their formulations to protect against multiple VOCs. Almost seventy years ago, the WHO Global Influenza Program (established in 1952) faced similar problems. The program organized and expanded a worldwide network of regional and national reference laboratories that cooperate to this day. Every six months—in March for the Northern hemisphere and September for the Southern hemisphere—an advisory committee identifies four circulating influenza virus strains for inclusion in upcoming seasonal influenza vaccines. After review by national health authorities, vaccine manufacturers have roughly six months for scale-up, production, and distribution. Health care services then have another three months to administer influenza vaccines worldwide. Although WHO's surveillance and advisory roles have proven successful for influenza, it is evident that SARS-CoV-2 has spread and diversified so rapidly that similar but more frequent advisory assessments may be required.

Up-to-date COVID-19 vaccines must be paired with equitable access to them. In April 2020, the access to COVID-19 Tools Accelerator (ACT) and accompanying COVID-19 Vaccines Global Access (COVAX) initiatives were established to quantify needs and supply doses of COVID-19 vaccines to low-to-middle-income countries. In addition, these two initiatives serve to facilitate voluntary licensing agreements and expedite not-for-profit global production of COVID-19 vaccines, treatments, and diagnostics. By offering timely vaccine advisory assessments, the blueprint could advance the goals of the ACT and COVAX initiatives.

The American-based National Center for Biotechnology Information established a genomic database for influenza viruses and started accumulating large numbers of genome sequences in 2002. Because of international mistrusts—solidified during the 2007 WHA—the European-based GISAID initiative was established to provide open access to influenza virus sequences in 2008. During the early "Public Health Emergency of International Concern" phase, GISAID began sharing access to novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) sequences on January 10, 2020, which permitted the initial development of diagnostics and vaccines. Over the past 18 months, GISAID's online data platform has accumulated more than one million coronavirus sequences from 172 countries and territories. However, the GISAID platform is designed for depositing and sharing primarily SARS-CoV-2 genome sequences with only limited metadata, such as locations, dates, authorships. To support the blueprint, the GISAID platform could be expanded to accommodate and associate three domains of data and metadata: epidemiologic, genomic and immunologic. GISAID could also warehouse metadata that document laboratory methods and quality measures.

Many countries maintain institutions that correspond to those of the United States, European Union, and China. For the COVID-19 pandemic, their key activities include establishing standard procedures, performing widespread epidemiologic surveillance, and conducting laboratory testing and analysis of samples. To support the blueprint, experts within these national centers could be recruited to lead and coordinate field-based and laboratory-based efforts in their respective geographic regions.

Three new and significant programs could also align with the blueprint:

- The WHO Hub for Pandemic and Epidemic Intelligence, announced by Chancellor Angela Merkel in May 2021, would be a global platform and collaboration of countries for driving innovations, creating linkages of diverse data, and implementing models and tools for "infodemics."

- The Global Pandemic Radar announced by Prime Minister Boris Johnson in May 2021, would identify and track new COVID variants and partner with nations to develop an advanced international pathogen surveillance network.

- The Pandemic Prevention Institute, announced by Rockefeller Foundation President Rajiv Shah in June 2021, would strengthen abilities to sequence and share genomic information in sub-Saharan Africa, India, and the United States, and would optimize bioinformatics tools for real-time understanding of viral evolution. Although the "next pandemic" and "all viruses" themes within these programs are laudable, dealing with the ongoing SARS-CoV-2 VOC challenge should be the prime objective.

Because of prior misjudgments and persisting inequalities, the amounts of good will, cooperation and sharing among 2005 IHR and 2007 WHA "states parties" has continued to erode. In the foreseeable era of polarization among superpowers, namely those involving the United States and China, there could be many lost opportunities for international collaboration. In the face of such challenges, will leaders of key nations agree on a common vision that builds a unified COVID-19 surveillance program? In the era of relentless variants of concern, the answer should be: Yes!