For a health system repeatedly pressured by outbreaks, the arrival of a single patient can be an early test of its readiness. Such a moment occurred in December 2024, when a young man sought treatment at a small, rural clinic outside Lungi, Sierra Leone. He reported having fever, crushing fatigue, and a headache he could not shake, which led community health workers to initially diagnose malaria. Staff treated him for presumed malaria without success, so he turned to traditional remedies. Only weeks later did laboratory testing reveal mpox, making him the earliest documented patient during what has become the country's largest mpox outbreak.

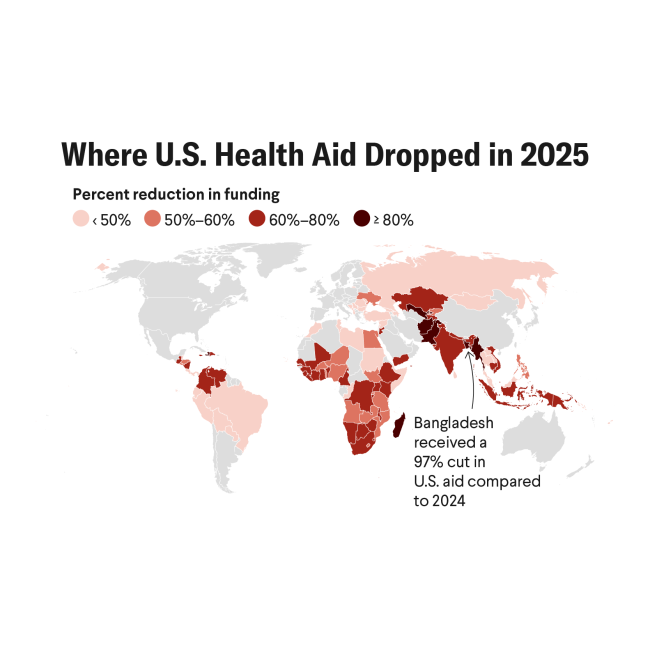

Mpox spreads through close contact with infected individuals, bodily fluids, or contaminated materials. Between January 1 and June 7, 2025, Sierra Leone recorded 3,782 laboratory-confirmed mpox infections and 20 deaths. Eighty percent of these cases occurred in Freetown, the capital. In early June, the country accounted for more than half of all cases across the continent. As Africa Centers for Disease Control (CDC) Director-General Jean Kaseya warned, mpox is already "spilling over into Togo and Ghana, driven by weak health systems and a critical shortage of vaccines, diagnostics, and treatments." Liberia has listed more than 800 suspected cases.

Lessons learned during the 2014–16 Ebola outbreak and COVID-19 pandemic were supposed to prevent this international spillover. Community health workers (CHWs), formally integrated in Sierra Leone's health system since 2012, remain central to surveillance, risk communication, and vaccine delivery. Despite their proven value, many CHWs have not been mobilized during the current outbreak because of funding constraints.

On the positive side, digital tools piloted during Ebola now support real-time case reporting and laboratory coordination, while graduates of the World Health Organization (WHO)–led Structured Operational Research and Training IniTiative (known as SORT IT) are guiding district-level responses and strengthening data use. Neighboring countries such as Liberia and Guinea similarly enhanced laboratory systems, quarantine protocols, and cross-border coordination during COVID-19, measures mirrored in Sierra Leone's approach. These upgrades in data speed, laboratory reach, and cross-border intelligence are now the backbone of a system under strain as mpox accelerates.

Paper Treaties, Empty Freezers

In 2021, the Independent Panel on Pandemic Preparedness [PDF] warned that "weak links at every point" had prolonged the COVID-19 disaster and called for a binding international treaty grounded in equity and rapid data exchange. That call was answered, at least on paper. In mid-May, the World Health Assembly approved and adopted the text of the Pandemic Agreement. The treaty, which has not been ratified or gone into force, would require countries to upload pathogen genetic data within 48 hours. It would also oblige manufacturers to reserve 20% of every future pandemic stockpile. Half would be donated. The other half would be sold at "affordable" prices guided by public health need.

These upgrades in data speed, laboratory reach, and cross-border intelligence are now the backbone of a system under strain as mpox accelerates

However, those treaty promises are tested against realities on the ground. Sierra Leone's experience illustrates this gap vividly. The country has relied on ring-vaccination—immunizing every confirmed case's close contacts, and the contacts of those contacts, to contain transmission—but the campaign was hobbled long before the first nurse uncapped a syringe.

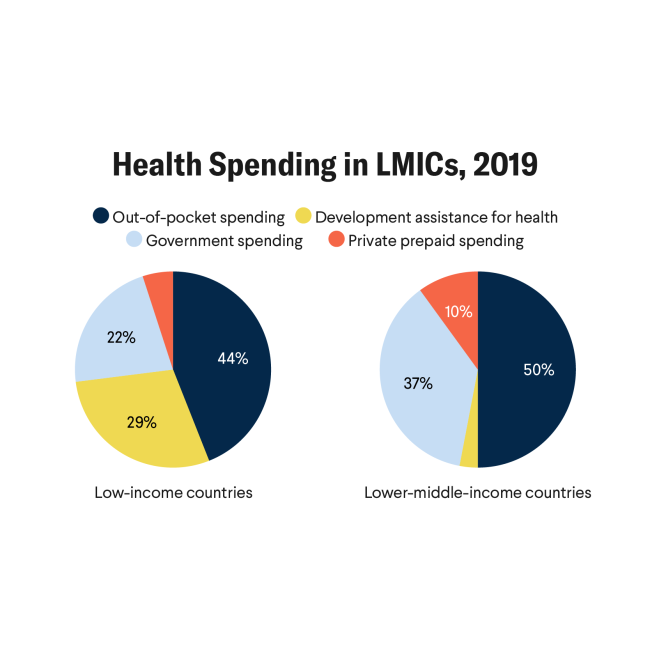

In September 2024, the Africa CDC and the WHO issued a Mpox Continental Preparedness and Response Plan for Africa that called for vaccinating 10 million of 13 million eligible people over six months. By May 29, only 720,000 people had received a dose.

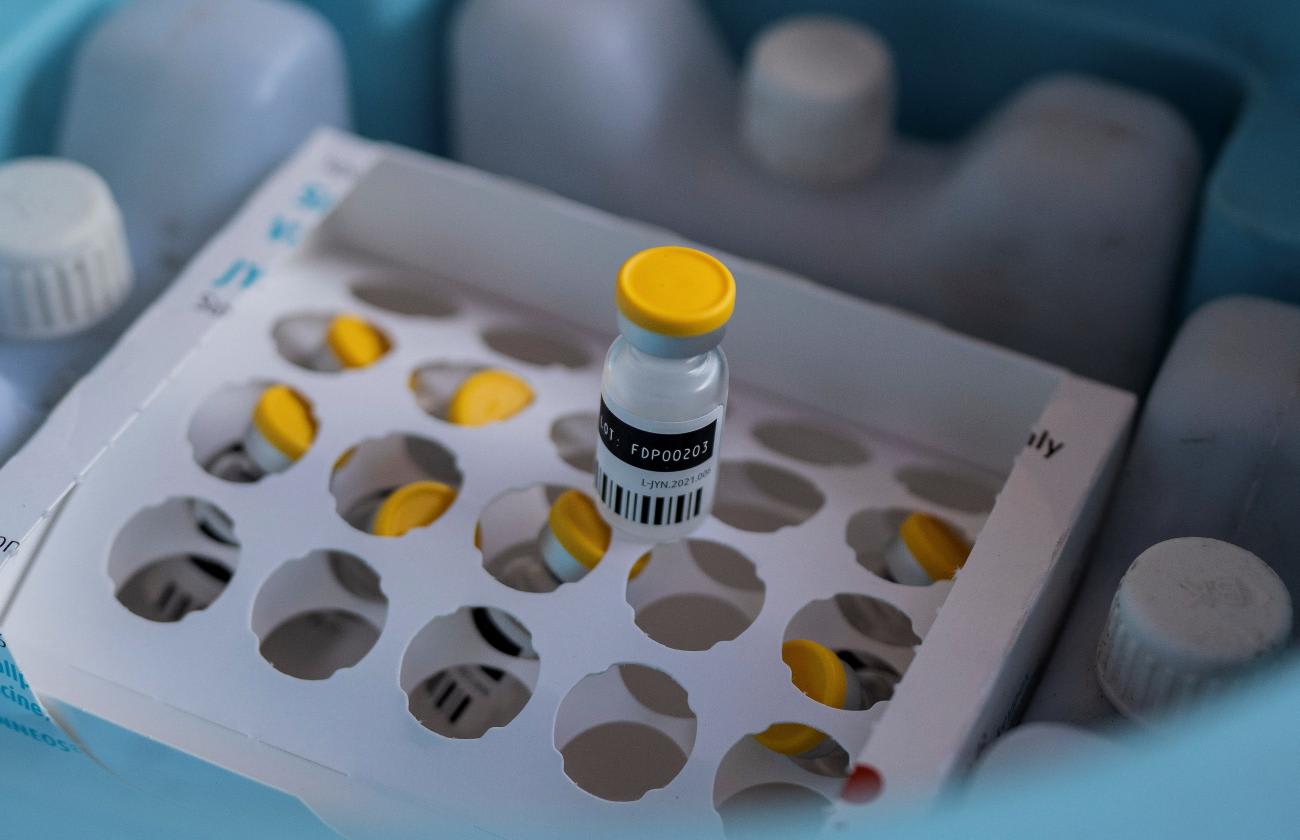

Freetown received vaccine shipments in dribs and drabs. The Ministry of Health's initial request for 429,000 doses yielded just 78,300 by mid-May, a further 20,000-doses gifted from the United Arab Emirates landing on June 5, weeks after secondary clusters were already spreading.

Evidence from Ebola's "ring-vaccination" trial in Guinea showed that vaccinating contacts within 10 days of symptom onset cut secondary infections to zero after day 10. The finding matters for mpox because, as true of Ebola, the virus spreads mainly through close bodily contact and contaminated fluids, so creating an immune ring around each case can break transmission chains. For mpox, the priority list is clear: frontline health workers, immunocompromised patients, and confirmed contacts.

Yet achieving this targeted vaccination relies heavily on cold-chain logistics, a persistent challenge in Sierra Leone. As of June 22, only two of Sierra Leone's six ultra-cold freezers were functional [PDF], and both are in Freetown. District vaccinators must haul every vial over flood-prone roads, stretching a sprint-speed ring-vaccination strategy into a slow relay.

The scarcity of vaccines has ethical consequences. Jedidah Johnson, a young physician based in southern Sierra Leone, explained this dilemma in a May social media post during home isolation. After a visit to 34 Military Hospital in Freetown, where immunocompromised patients were cared for by colleagues in worn protective gear, she wrote, "Fairness isn't always about treating everyone equally. I was not vaccinated because the country does not have enough doses. Yet I know people with no exposure, no underlying health issues, who have been vaccinated. Equity isn't equal distribution; it's about fair distribution. Distribution that is based on need and risk."

Johnson clarified her comments as advocacy, not complaint. Still, the frustration underscores how fragile confidence in public institutions becomes when scarcity collides with opaque prioritization.

This lack of clarity compound other critical gaps, such as contact-tracing capacity. Africa CDC data shows that only one named contact per confirmed case is identified in Sierra Leone, far below the 20 expected in the region. Poor tracing makes it harder to identify hotspots and delays distribution of vaccine vials that would break transmission. Every logistical delay opens a new transmission window, and every new cluster siphoned doses from the communities still waiting. The pattern underscores the brutal lesson of this outbreak: When vaccines arrive late, promises of equity arrive later still.

Shortfalls hit hardest on the front line. In early May, only 60 staffed isolation beds were available nationwide. The National Public Health Agency (NPHA), launched in 2023 and operational since 2024, has since opened a 400-bed treatment center at the Police Training School in Hastings, Freetown. However, nurses still report shortages of gowns and intravenous fluids.

Who Gets Sick—and Why It Matters

Demographics complicate control. The median patient age is 25 years. Rural clusters involve men in their 30s; urban cases skew toward young women. Transmission patterns reflect dense and interconnected sexual and social networks, underscoring that punitive measures (such as forced isolation or intrusive contact tracing) drive cases underground and ultimately backfire. The Ministry of Health therefore embeds mpox care in HIV and sexually transmitted infection clinics that are already trusted to navigate stigma.

To regain ground, the NPHA launched Operation Find Them All, combining seasoned community mobilizers with tablet-based dashboards and solar-powered devices. But tracing teams cannot chase rumors if motorbikes lack fuel or stipends arrive late. Technology cannot plug financial holes. Laboratory leaders are pushing to station palm-sized genetic sequencers closer to outbreak zones. The tools cost less than a four-wheel-drive ambulance but face six-month procurement delays. Similar units delivered during COVID-19 now sit idle for want of maintenance contracts.

Relocating handheld sequencers from Freetown to district labs could shorten lineage-identification time from days to hours, giving health teams same-day answers about whether the virus is changing, as Guinea managed during its 2015 Ebola outbreak. These tools need sustained support: maintenance, supplies, and travel allowances. Equipment, people, and money remain the inseparable tripod of preparedness.

None of these gaps are unique to Sierra Leone. What distinguishes the country is its unwilling intimacy with epidemic trauma, and its experience of turning pain into incremental institutional reform. The NPHA, which did not exist a decade ago, has already shortened the chain of command between district alerts and national decision-making. Civil society monitors, trained during the Ebola recovery, now track rumors through WhatsApp groups and relay them to risk communication specialists, who can issue clarifications within hours.

Sierra Leone's first treaty scorecard, due in May 2026, will ask why genetic samples sometimes take longer to cross a district on a motorbike than viral isolates take to reach European labs, and why vaccine queues can appear to favor the well connected over those most at risk. The gaps are not uniquely Sierra Leonean; they are global weak links the Pandemic Agreement seeks to mend.

Skeptics will argue that all this is aspirational, that amid climate shocks, conflict, and antimicrobial resistance, a virus with single-digit fatality rate will never attract the resources once marshaled for Ebola or COVID-19. The counterargument is historical. Epidemics have a habit of revealing whether the last crisis was truly instructive or merely traumatic. Sierra Leone has paid dearly for its lessons. What remains is to act, and in so doing to help bring the new Pandemic Agreement to life. Fairness will be measured not by speeches in Geneva but by how quickly a doctor in Freetown receives the same vaccine she nearly went without while caring for others.