In late September, the UN General Assembly (UNGA) released a political declaration on a future vision for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) and the promotion of mental health and well-being. It outlines a framework to achieve these goals by 2030 and beyond.

NCDs present a substantial and growing challenge to public health worldwide. In 2021, 43 million people—73% of them concentrated in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs)—died from these chronic diseases.

The UNGA high-level meeting was on course to be a flagship moment for the dual crisis of NCDs and mental illness, advancing an agenda and calling for member states to renew their commitments. Yet, despite receiving support from multiple nations, the declaration was sidetracked after U.S. Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. said that the United States would reject the draft because it "exceeds the UN's proper role while ignoring the most pressing health issues."

The lack of political interest relative to that in infectious epidemics casts a shadow on national efforts to improve NCD medicine access

The political declaration is noteworthy because the growing burden of NCDs affects more than health and well-being. It places entire societies and economies at risk given the substantial expected losses in human capital and capacity.

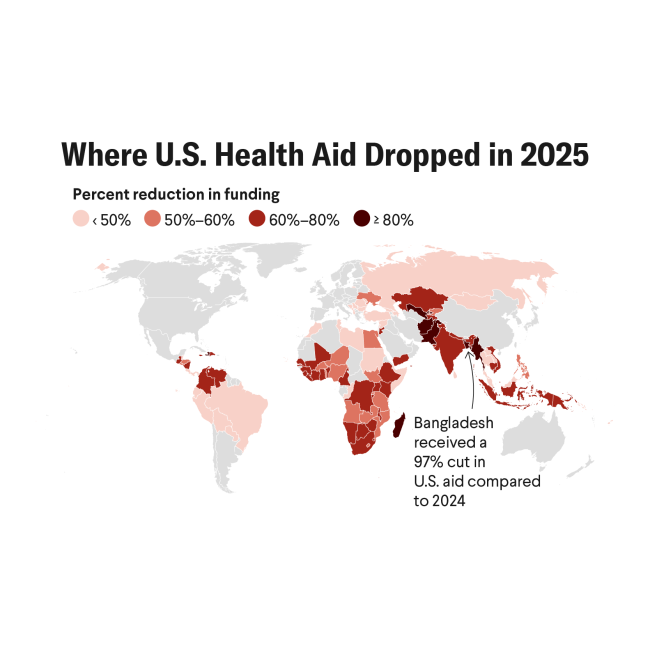

According to the Council on Foreign Relations Task Force on NCDs in LMICs, these diseases could incur $21.3 trillion in economic losses in developing countries over two decades, roughly equivalent to their entire economic output in 2013. The NCD alliance reports that the world economy is projected to lose $47 trillion between 2011 and 2030, averaging more than $2 trillion a year. Such losses would undermine trade and destabilize LMIC governments, many of which are experiencing record levels of debt and financial complications due to recent pullbacks in foreign assistance.

The United Nations and NCD Medicines: Much Talk, Little Progress

Prior to this year, the United Nations had worked to highlight the issue of access to NCD medicines during previous meetings. The 2014 UN High-Level Review garnered national commitments to address NCD burden and included a comprehensive accounting of progress since a 2011 NCD summit [PDF]. In 2018, the third such meeting on NCDs produced a political declaration [PDF] that again made similar commitments and urged accelerated action on integrating NCDs into primary care and universal health care.

These meetings, and similar sessions held at other international gatherings such as the World Health Assembly, have proposed global targets, which, as true of many declarations, have led many countries to develop national NCD strategies and plans. The World Health Organization (WHO) and many countries have also updated their essential medicines lists to include more NCD drugs and have offered advice for national targets, such as aiming toward 80% availability of affordable essential NCD medicines and technologies by 2025.

Many pilot programs and initiatives to improve NCD medicine access have launched as well. Programs such as the Defeat-NCD Partnership, the St. Jude Global Platform for Access to Childhood Cancer Medicines, the WHO's Global Hearts Initiative, Resolve to Save Lives, Access Accelerated, and Access to Oncology Medicines, were created to mitigate NCDs and provide global access to medicines and care.

Yet the world is far from achieving the 80% access target because, unlike in the infectious disease field—namely, HIV/AIDS, malaria, tuberculosis, and vaccines—no large-scale donor financing for the procurement of NCD medicines is available.

These financial constraints compound with the high price of NCD medicines for both patented and generic drugs.

This pattern further limits access because drug prices for NCD medicines are significantly more than for acute medicines both in nonprofit and private drug outlets. Unlike fast-moving epidemics, NCDs are seen as slow burning, which results in procrastination and deprioritization among national governments and global donor agencies.

The lack of political interest relative to that in infectious epidemics casts a shadow on national efforts to improve NCD medicine access. For example, a health minister allocating large resources toward medicines could worry that these efforts will be perceived as pursuing an agenda for the pharmaceutical industry, given that these companies are often seen as the primary force behind requests for improving access to NCD medicines.

Yet the pharmaceutical industry faces distinct challenges because it cannot simply sell a higher volume of drugs even if the companies reduce prices. Barriers such as a lack of service delivery infrastructure (such as well-equipped clinics, trained specialists, or equipment and labs for diagnosis medicines), health worker shortages, and training gaps hinder drug distribution and accessibility. Simply reducing drug prices will not resolve those fundamental problems.

Breaking the Cycle of Inaction

Stemming NCD burden requires a reevaluation of how nations can expand access to necessary medications and what can be accomplished to ensure care for those in need.

First, if health budgets shrink because of foreign aid cuts, out-of-pocket payments by patients could remain the mainstay for NCD medicines purchasing. Even in a scenario in which LMICs could cofinance the provision of NCD medicines, such a move would add a large number of patients that require care to health systems that are not necessarily equipped to handle the burden and would still cause significant budget stress regardless of price reductions given that governments would have to find a way to fund medicine provisions for a larger population.

Groups should reconsider whether bundling cancer, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes care with other NCDs is the wisest approach

The best path forward pragmatically in the nearer term would be to let people continue to access NCD medicines through private channels, such as private pharmacies, where they can pay for medications out of pocket. However, to streamline accessibility while preserving quality, out-of-pocket prices will need to decrease.

A number of new companies—such as MYDAWA, Maisha Meds, SwipeRx, reach52, mPharma, and Kasha—have emerged to streamline the NCD medicine supply chain and reduce out-of-pocket patient prices by lowering the number of intermediaries that would charge a margin for the distribution of NCD medicines. These companies also connect retail pharmacies directly to manufacturers, allowing medicines to reach more patients directly.

Second, planning strategies should be informed by better forecasts of demand so that vested interests have a clearer picture of the financial needs, what types of products are required, and how many patients can realistically be put on treatment. Early attempts by the WHO and the Coalition for NCD Medicines created a forecasting program to improve data quality and mobilize funding for NCD medicines.

Third, groups should reconsider whether bundling cancer, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes care with other NCDs is the wisest approach. Medicines and health technologies for these three diseases have distinct barriers for access. In the cancer field, a lack of diagnostic infrastructure and too few trained medical professionals remain important challenges. When it comes to cardiovascular disease, including primary and secondary prevention with generic statins and antihypertensives, the problems are less about infrastructure and human capital and more about the high costs of medicines. Diabetes management experiences a combination of these, as evidenced by the difficulties in accessing insulin and its high price. Placing cancer, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes on a specialized track could permit more meaningful progress on NCD political declarations, target commitments, and project design.

Although the conversation around NCD treatment and prevention remains central at policy platforms such as the UNGA and the World Health Assembly, many optimistic pledges and strategies have yet to make a meaningful impact on NCD medicine access. By aligning strategies with the realities surrounding the procurement and distribution of NCD medicines and increasing the accountability mechanisms for countries around the world, national leaders could save money and countless lives.