The United States economy has lost more than 30 million jobs since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, with unemployment reaching levels unseen since the Great Depression. But the skyrocketing unemployment rate is just the beginning of the havoc this economic downturn will wreak on the daily lives and health of millions of Americans. The resulting psychological stress and social isolation threaten to push the U.S. opioid epidemic to a new level, unraveling the progress made in the last several years.

Skyrocketing unemployment rate is just the beginning of the havoc

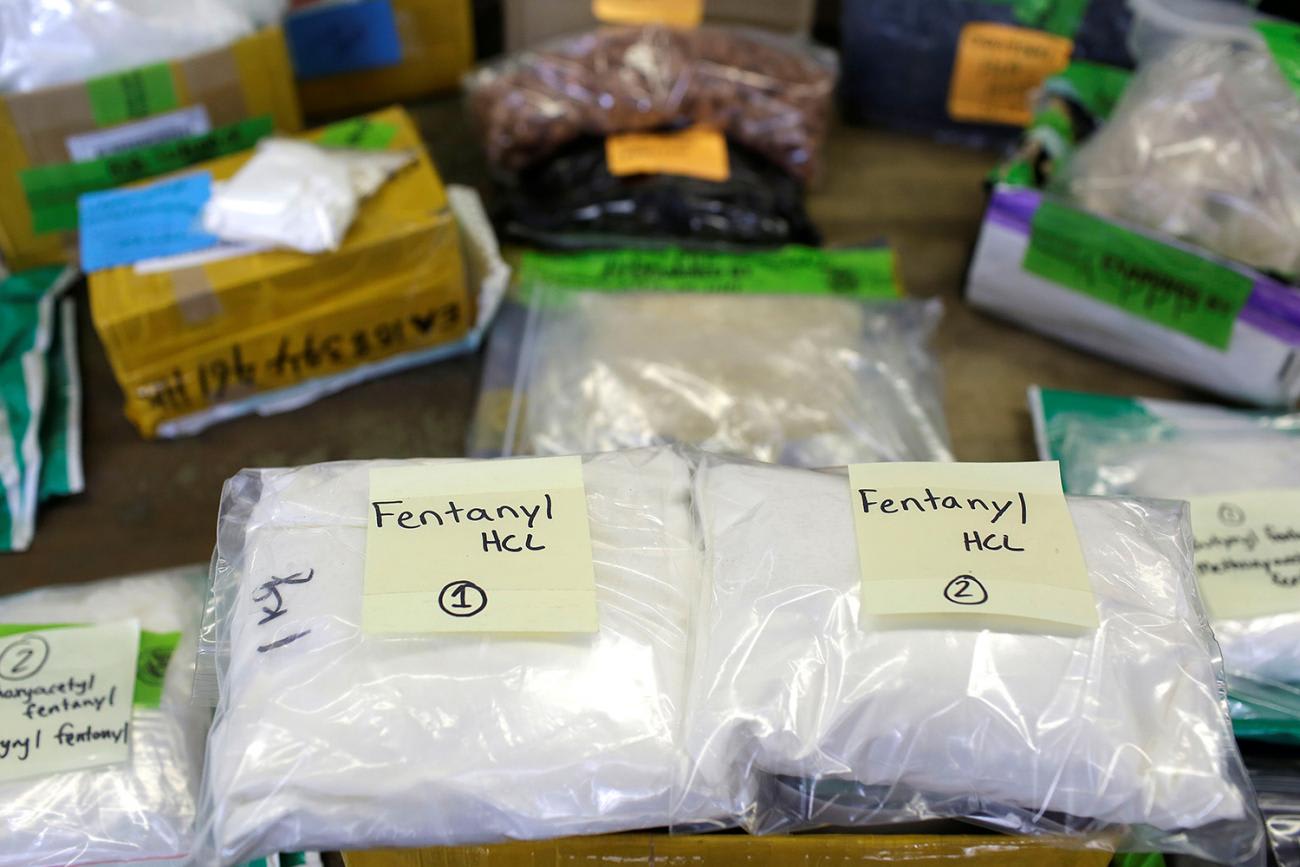

Over the past decade, the U.S. opioid epidemic has evolved from one of prescription opioids, to one of heroin, to one of fentanyl. With the COVID-19 pandemic limiting the supply of Chinese-manufactured fentanyl, coupled with the expected increase in drug use during an economic downturn—we expect to see a growing number of drug users, with many switching to drugs other than opioids to achieve their highs, leaving us on the precipice of a devastating new type of drug epidemic we are ill-equipped to handle.

An estimated ninety percent of illicit fentanyl in the United States comes from China, the vast majority shipped via mail or as cargo. But the COVID-19 epidemic has severely disrupted Chinese manufacturing, with quarantines and factory closures limiting manufacturing capacity and stifling trade routes. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, imports from China to the U.S. in March 2020 came in at a lower level than any month in the past ten years.

Just as the flow of more mainstream products like cell phones and textiles from China has slowed, so has the flow of fentanyl dried to a trickle

Even as factories slowly start to reopen, Chinese shipping remains severely disrupted—blocked roads and checkpoints continue to sever supply lines and impede the transportation of goods to and from docks. Future waves of spread of the coronavirus, like the one occurring this month in Beijing, threaten to further stifle trade for months or years to come. Just as the flow of more mainstream products like cell phones and textiles from China has slowed, so has the flow of fentanyl dried to a trickle. Several reports have already documented the increasing street price of fentanyl in response to its limited supply. An increase in the price of opioids threatens to usher even more opioid users towards methamphetamine, or meth, which remains an abundant and relatively cheap alternative despite recent similar price increases.

The Silent Rise of an Addictive Killer

Even before the COVID-19 epidemic affected Chinese exports, meth had almost silently begun to join or replace fentanyl as a drug of choice for opioid users. A study of routinely collected urine samples published in the Journal of the American Medical Association Open Network showed that over the past six years, the number of people testing positive for meth has increased six-fold—an increase largely ignored while the federal crackdown focused on prescription painkiller abuse. As meth use has started spreading across the United States, many people already battling opioid addiction are now falling victim to meth.

The average person with an opioid addiction spending an estimated $22,810 to $91,250 per year on their addiction

This trend will only accelerate in the face of rising fentanyl prices because the need for a cheaper alternative to a costly addiction has been a key driver of the evolution of our drug use epidemic. In recent history, opioid addiction has been substantially more expensive than meth addiction, with the average person with an opioid addiction spending an estimated $22,810 to $91,250 per year on their addiction, compared to $12,775 and $38,325 for a person with an addiction to meth. While the exact changes in drug prices in recent months vary by region and are difficult to measure, one assumes that as the prices of illegal drugs increase everywhere due to limited supplies, some users will switch to the cheaper high available through meth use.

While the opioid epidemic takes more total lives at the moment, the exponential growth in meth-related deaths in recent years is staggering. The first decade of the opioid epidemic saw a fourfold increase in annual opioid-related mortality, from 3,400 in 1999 to 13,500 in 2009. This lies in stark contrast to meth-related deaths, which have quadrupled in half the amount of time from 2,600 in 2012 to 10,300 in 2017. The decreased availability of Chinese-made fentanyl, coupled with the despair of uncertainty and unemployment linked to the COVID-19 pandemic, may only serve to compound this dangerous rise in meth use.

Meth addiction is more difficult to treat than opioid addiction

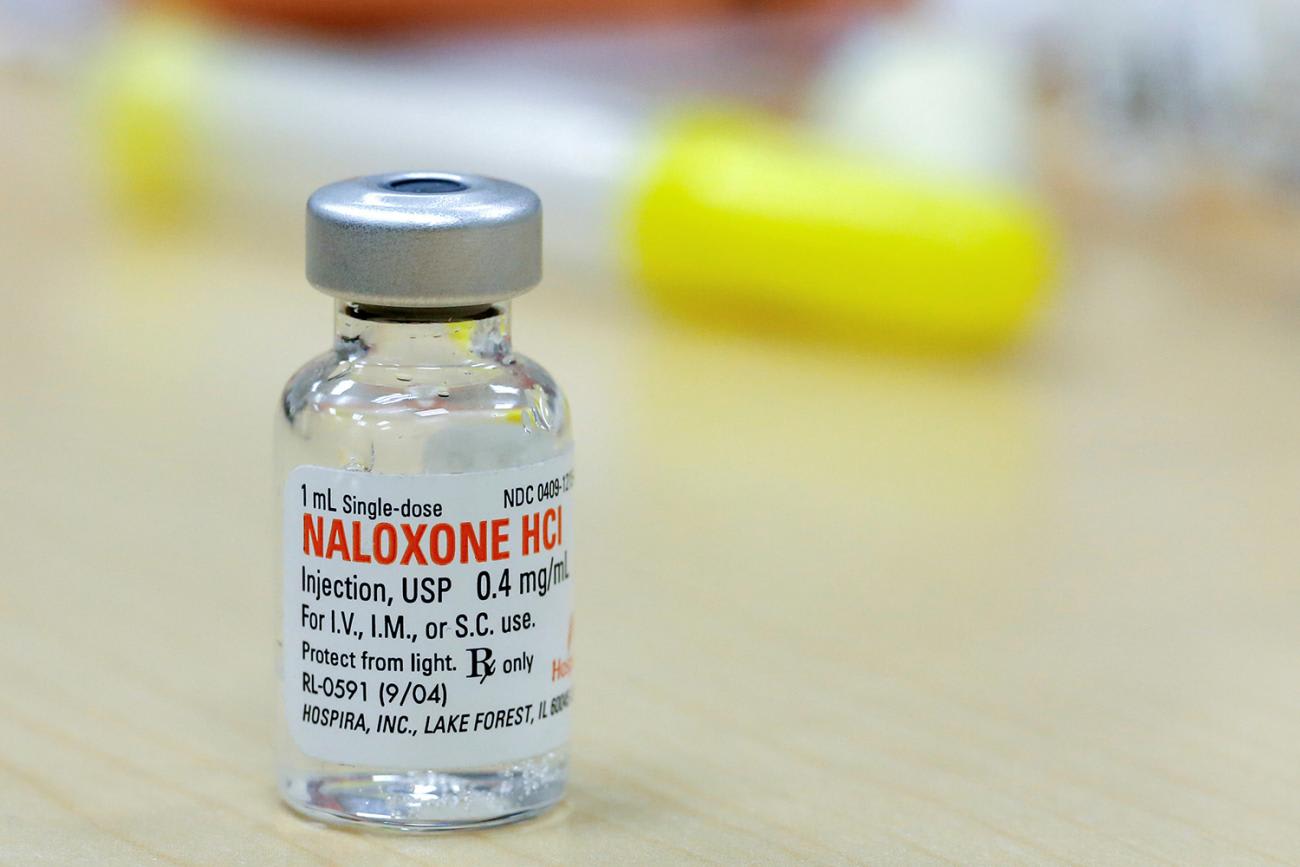

For the growing population of opioid and meth co-users, the risks are substantial. Mixing opioids with meth has been linked to increased risk of overdose compared to using opioids alone. Co-users are also less likely to respond successfully to opioid addiction treatment. Moreover, meth addiction is more difficult to treat than opioid addiction. There is no FDA approved medication to quell cravings, and no rescue medication like naloxone to rapidly address overdose.

In the small riverside town of Louisa, Kentucky, a community once ravaged by opioids, meth has sown new strife. Amid the widespread efforts to curb the opioid epidemic, meth use increased, and its dangerous side effects—including unpredictable outbursts and aggression—have bred fear and anger in the once peaceful community.

Meth-related deaths quadrupled from 2,600 in 2012 to 10,300 in 2017

But the story of Louisa, Kentucky is not unique—many places have witnessed a similar transition from opioids to meth, from South Carolina to New Hampshire and from Yakima, Washington to Yuma, Arizona. Just when many U.S. communities were beginning to see success in fighting the opioid epidemic, another wave lies on the horizon. Now that the COVID-19 pandemic has captured our collective attention, we must not forget about this second wave drug epidemic that's been swelling under the surface for years, threatening to unravel our opioid successes. In the midst of our current infectious disease and economic crises, the United States must prepare for this new lethal foe, against which our existing armory is ineffective.

What to do About the Meth Problem

Our response to this crisis should be multifaceted. Congress has already taken a crucial first step toward addressing meth use—a recent appropriations bill expands the scope of federal funding initially limited to combating opioid addiction to include funding to target addiction to stimulants like meth. Now states should take advantage of the available funding and funnel resources toward finding effective prevention and treatment measures against not only opioids, but also meth.

States should take advantage of the available funding and funnel resources toward finding effective prevention and treatment measures

In addition to heavy investment in the research, identification, and allocation of effective methamphetamine treatment, providers and policymakers must act to address the social determinants of substance abuse—unemployment, social isolation, and barriers to substance abuse treatment and mental health care access, all of which have been exacerbated by COVID-19. For any epidemic, whether caused by an infectious virus or an addictive substance, savvy prevention and early detection measures will save substantial resources, energy, and lives—much more so than our typical reactive approaches. Perseverance through the COVID-19 response and the subsequent economic and social recovery from the pandemic-induced lockdowns will depend upon the availability of workers, families, and communities that are both mentally and physically healthy.