Let's be honest: COVID-19 never was and never will be the "great equalizer" that people initially claimed it to be. In New York, for example, the case burden is highest in the Bronx and Queens, the two boroughs with the highest prevalence of poverty. Across the country, black Americans are dying disproportionately from COVID-19. Disproportionate rates of death are also being seen in Navajo Nation. In Arizona, Navajos make up 5 percent of the population, but 20 percent of the deaths from COVID-19. In New Mexico, Native Americans make up 11 percent of the population, but 31 percent of the cases. The virus has exploited and exposed the extant disparities and structural inequities already present in our society.

When this pandemic is under control, it will be tempting to declare success and return to the status quo

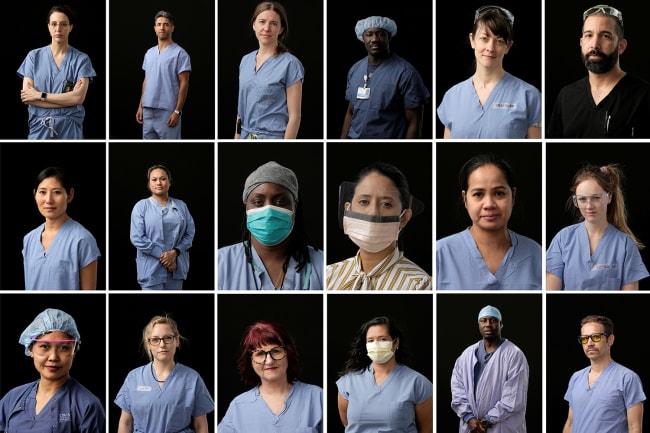

During the acute phase of this crisis, we at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Health, Equity, Action, and Leadership (HEAL) Initiative responded to Navajo Nation President Jonathan Nez's request and sent twenty-one health workers to three different sites on the Navajo Nation. This week, another wave of UCSF providers will be making the journey. When this pandemic is under control, it will be tempting to declare success and return to the status quo. But returning to this former state of affairs is not something for which we should settle. Structural inequity is an insidious disease in its own right, and we cannot continue to let it smolder. Now is the time to push both for structural changes to the underfunded and understaffed U.S. Indian Health Service agency—but also for narrative changes that respect culture and acknowledge history as we push forward.

Transitioning the Message

Media attention on Navajo Nation is so useful in bringing attention to long neglected issues. But we must entrench our understanding of this moment in historical injustices and a way forward. This momentum must not be temporary. We must instead transition from a message of charity to one of advocacy for long-lasting equity in words, dollars, and actions.

We need to educate ourselves on the history that has shaped today

We write this with the awareness of our position as outsider/insiders, as part of the invited UCSF contingent and as people who have made a commitment to the Navajo Nation. We do our best every day to listen and learn knowing that solidarity is a process that cannot be reduced to a simple transfer of resources, especially if that transfer is only temporary. It's also worth noting the absence of Navajo voices in this piece as many of our Navajo colleagues require extensive permissions for media interviews and publications. If we are to work with indigenous peoples, we must take a serious look at what we mean when we describe our work as equitable or "showing solidarity."

So, what would true solidarity look like? First, it means showing up to work having done our homework. We need to educate ourselves on the history that has shaped today.

A Tragically Underfunded U.S. Agency

We must recognize that the Navajo people have a dedicated cadre of health care professionals and public figures who are working under serious resource shortages from years of neglect. While funding for the U.S. Indian Health Services has grown marginally in recent years, communities say that the agency is still tragically underfunded, held for years at levels less than one third the rate of other federally protected populations like senior citizens and veterans. Massive, cumulative, and chronic staff shortages, underfunding, and budget uncertainty weaken the health care system for indigenous peoples making them suboptimal at best and particularly vulnerable in COVID-19 times.

Massive, cumulative, and chronic staff shortages, underfunding, and budget uncertainty weaken the health care system for indigenous peoples

Recognizing this history is crucial in shaping the narrative around how we got here and what the next steps should be. Promoting pathways of education for native youth to create more native health care providers while incentivizing long-term employment of health care workers at Indian Health Services sites, advocating for funding the Indian Health Services to meet its budgetary needs, and working to maintain native health services as a national priority are a few ways to show true solidarity. Any efforts to promote sustainable health care on the reservation will also need to acknowledge the 1979 nuclear disaster at the Church Rock uranium mine, where an accident released more radiation than the higher profile Three Mile Island incident that same year. Trust eroded by the federal government's continued inadequate response in its aftermath. We could use our voices and privilege to amplify long-standing calls for uranium mining cleanup and advocate against recent moves by the federal government to revive uranium mining. This is not a matter of charity. This is a matter of fulfilling the legal agreement made between the federal government and indigenous peoples.

Next, we must acknowledge and defer to the people in the community who have been on the ground working long before we ever arrived and will be there long after the news cameras depart. They are the experts with whom we must partner in order to do meaningful, long-lasting work. As outsiders we must ask folks what they need and respond to their wants instead of our wants, respect desires for not communicating to the media about their internal communities, honor the trauma that families are facing today with the hyper concentration of infections on top of historical trauma, and stay and serve in the places of greatest need.

Let us make a commitment to true solidarity

History does not begin and end within the imagination of outsiders such as us. The histories of the Navajo and other indigenous peoples are just some among many that reveal the brutal and ongoing effects of imperialism and the ways in which COVID-19 exacerbates the fault lines of these inequities. As we shine a light on these inequities, let us make a commitment to true solidarity. Let us acknowledge this history, give due respect to community leaders, and advocate for structural change.