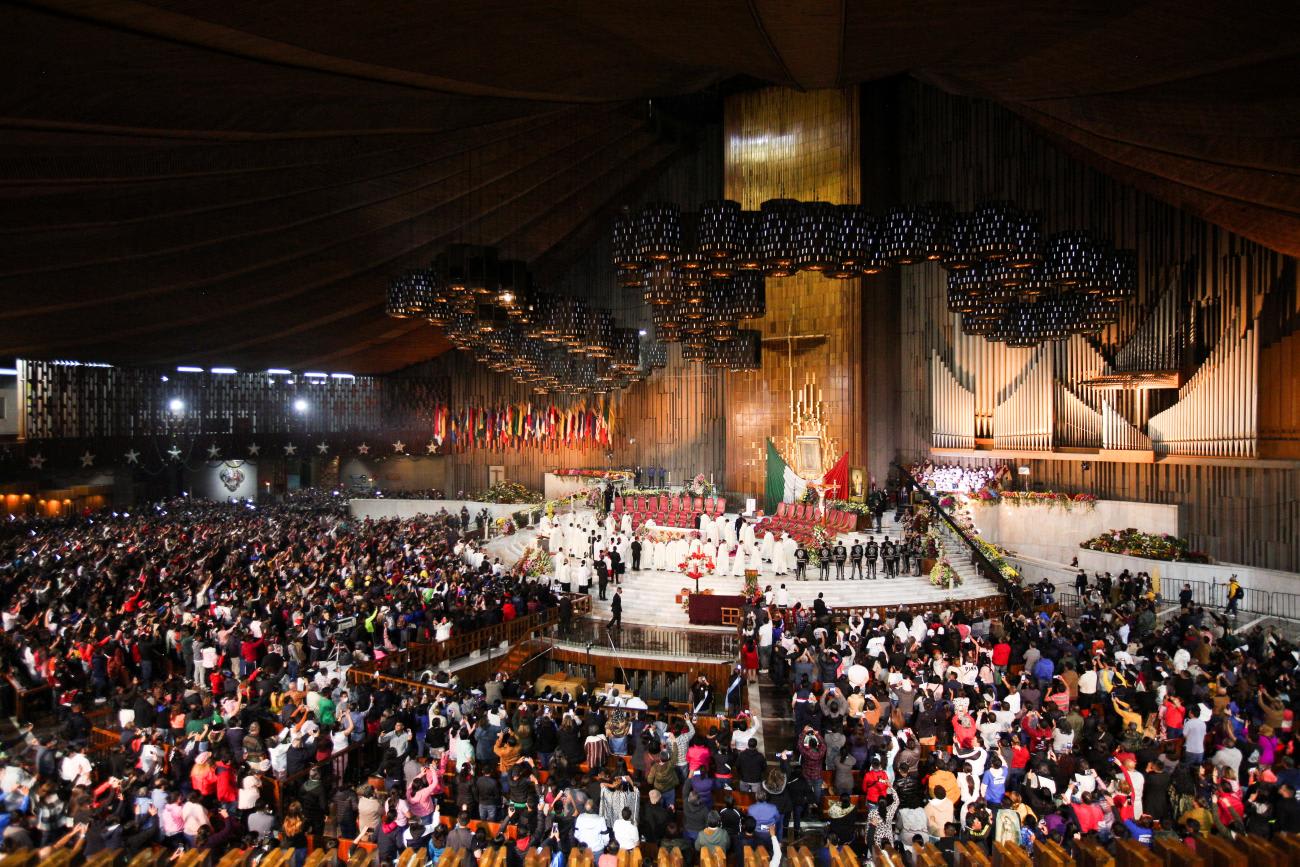

The history between women's rights and Christianity in Mexico City is complicated. More recently, many women in Mexico's capital have become disillusioned with the Catholic Church and its teachings and have changed their relationship with the church to one that is less focused on its moral teachings and more centered on their personal faith. For some women, this shift in spirituality has helped them reconcile their religion with the difficult decision to obtain an abortion.

The issue of abortion has been debated for years in Mexico, where 81 percent of the country's population identifies as Catholic. Abortion has always been decided on a state level, and most states only allow abortions under limited circumstances; this has only increased the rates of unsafe abortions being performed. It was not until 2007, that Mexico City passed legislation that decriminalized abortion in the first 12 weeks (3 months) of pregnancy. As legal abortion services became available in Mexico City, the number of health-care procedures for abortion increased; from April 2007, when legal abortions became available, and March 2021, there were 234,513 legal abortions performed—162,189 for women who resided in Mexico City, while more than 63,000 women came from neighboring states, many of which do not allow legal abortions.

81 percent of Mexico's population identifies as Catholic

The increasing number of abortions in Mexico City is compelling and points to a larger, more underexplored issue: how Catholic women in Mexico come to terms with their reproductive decisions. It also highlights the importance of theological discussions surrounding this topic. In the field of theology, women are often left behind. In the Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion, Michelle Gonzales says that contributions to theology from the voices of Latinas are often branded as "feminist theology" and are being lost to that label. Gonzales writes, "Due to a lack of attention to the concerns and insights of feminist thinkers, Latinos, for the most part, have marginalized women's contributions as exclusively feminist critiques and/or as pertaining solely to women's concerns. Thus nearly all theology written by women is uncritically deemed "feminist," a term that remains inadequately defined within Latino/a theology." When it comes to issues of reproductive rights within Latina theology, she says we may be losing valuable accounts regarding the identity of Christian Latinas and their beliefs about more controversial issues.

When Elyse Ona Singer published her article in Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry in 2017, she reported that of around 170,000 abortions performed in Mexico City between 2007 and 2017, more than 60 percent were among self-reported Catholic women. Singer engaged in eighteen months of research to learn how women who chose to get abortions morally reconciled their decisions with the Catholic Church's teachings and their religious beliefs.

In an email, Singer told Think Global Health, "Against the stereotype of the guilt-laden Catholic woman, many of the women I interviewed were emphatic in pointing out that Catholic leaders had no place condemning their reproductive decisions in light of widespread hypocrisy and scandal within the Church…Rather than adhering to Catholic dogma, many women turned directly to God to ask for forgiveness without compromising their faith."

Women found external reasons as to why they kept their decision and their faith separate, Singer said. By seeing Catholicism as something more personal—as their own personal connection with God—they were able to look past certain restrictions of the church. Many of the women mentioned the moral atrocities the Church, and some of its members, have committed. One of the women Singer interviewed said, "That's why I don't think God is going to punish me [for having an abortion] … I've seen that Catholicism, my family's religion, is so hypocritical… maybe the Catholic Church is not okay with [abortion], but [we need] to look at everything that representatives of the Church do, the powerful people of the Catholic Church…"

The women interviewed by Singer did not only question the morality of the Church and its own recent scandals, but also the church's criticism and treatment of people in lower socioeconomic positions. In her article in Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry, Singer wrote, "Perceived economic corruption on the part of Church officials was an especially egregious offense for the women in my study, whose abortion decisions were often carried out as a means to safeguard their families in a climate of economic scarcity."

The women were mostly speaking about how the Catholic Church did little to help their situations, how they preached about helping, and then fell short. This is yet another place where the women were able to separate their feelings toward the church and its officials from their own relationship with God.

The debate over abortion in all sectors of society is far from over, but looking at the way women in a predominantly Catholic country reconcile their right to choose with their religion is an important addition to the conversations happening in feminist theology and Latina theology. Often, the way women interact with religion is discounted, but examining how women in a predominantly Catholic society view abortion and women's reproductive rights gives a new understanding to the way people experience their faith.

"But more important in informing these decisions than disillusionment with the Church, I believe, was the legality and relative accessibility of abortion in the Mexican capital since 2007," said Singer.

As the conversation around abortion continues, it opens the doors to seeing this as a viable option for women regardless of political or religious beliefs, Singer wrote. "This discursive transformation has been effective in cleaving open more space for women to see abortion as a viable option, and one that is grounded in liberal notions of women's rights and equality as equal citizens before the law. While the Church continues to wield considerable popular and political power in Mexico, today more than ever, abortion is increasingly accepted, particularly in cosmopolitan centers like Mexico City," she said.