The consequences of the Donald Trump administration's decision to decimate U.S. foreign assistance for Africa are not hard to find. Global health professionals have forecast soaring numbers of malaria, tuberculosis, and polio infections; more acute and fatal cases of malnutrition; more HIV-related deaths; and rising maternal and child mortality—and that is just in the global health space the United States long dominated. Programs to fight corruption, improve food security, prevent radicalization, expand access to power, and combat wildlife trafficking have also disappeared.

Yet African leaders are notably not sounding the alarm, at least not loudly. To the extent that they have publicly addressed the abrupt U.S. policy change, remarks have been understated rather than alarmist. Given the life and death issues at stake, downplaying the implications seems counterintuitive.

No political leader wishes to give the impression that their constituents' well-being depends on the generosity of distant powers. In fact, the weaker the state, the harder leaders work to project an air of power and authority. It would be a vulnerability to suggest that citizens are in crisis because of a decision made in Washington that cannot be rectified by leadership at home. Particularly for leaders long frustrated by Afro-pessimism, little is to be gained by emphasizing the costs of the absence of the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID).

The realities of foreign assistance can be insufferably patronizing for those on the receiving end

Long-standing ambivalence about the development sector also means that few prominent voices in the region wish to publicly mourn its loss, even if they privately acknowledge the significant role it has played in providing basic services. Much of the foreign assistance budget has been allocated to large, U.S.-based organizations to implement programs, a reality not lost on Africans frustrated with the slow pace of localization efforts [PDF]. Moreover, the off-putting power dynamics between development donors and recipients have long rankled African societies. Senior officials responsible to their citizens resent foreigners directing some of their decisions and priorities, and they chafe at endless reporting demands from officious Americans. Despite the efforts of many excellent foreign assistance professionals, the realities of foreign assistance can be insufferably patronizing for those on the receiving end.

Those two factors inform the popularity of the wake-up call response of many African leaders, from former Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta to Nigerian President Bola Tinubu to Zambian President Hakainde Hichilema. Characterizing the U.S. withdrawal from foreign assistance as a catalyst for a new era of African strength and self-reliance allows African politicians to emphasize their competence, dignity, and readiness to take on a challenge. The political appeal is undeniable and permits capitalizing on resentments accrued in earlier eras, when the United States used its foreign assistance as leverage to influence a recipient government's decisions. The loss of U.S. influence and leverage is a problem for Washington but could be perceived as liberating from across the Atlantic.

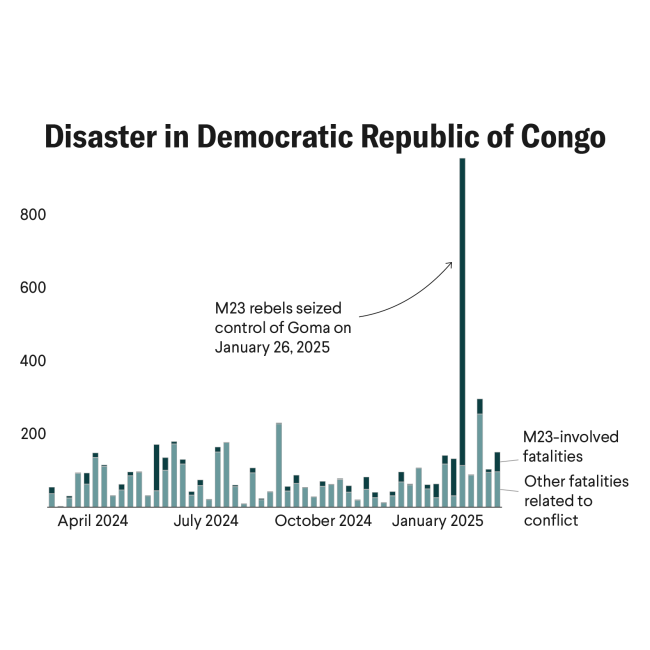

In addition, no one wishes to turn the eye of Sauron their way. The ferocity with which the Trump administration has turned on South Africa—vilifying the government, elevating extremists, refusing to attend Group of 20 (G20) meetings there, and declaring their ambassador in Washington persona non grata—illustrates the dangers of incurring Washington's wrath. Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) President Felix Tshisekedi is desperate for international assistance to cope with a massive security crisis in the east. Reading the room, he has proposed a minerals-for-security swap rather than dwelling on how DRC will be among the countries most affected by the decimation of U.S. foreign assistance. He is certainly not inclined to criticize U.S. policies and alienate the notoriously thin-skinned president of the United States.

One group of officials has been willing to point out the dangerous consequences of the assault on USAID: Chinese diplomats. China will not replace U.S. assistance, but it will relish the opportunity to contrast the United States with its self-professed status as a reliable partner. It's unsurprising that the United States' chief competitor would capitalize on Washington's decision to abandon a major tool of foreign policy. But for all the political motivations guiding official statements today, the reality of the situation will be measured in deaths, missed opportunities, and a sense that the United States is simply less relevant in Africa.

EDITOR'S NOTE: Caroline Hecht contributed research to this article.