Since its founding in 1948, the World Health Organization (WHO) has saved countless lives and, with adequate support, has the opportunity to save even more lives through investments in primary health. According to The Lancet Global Health, efforts to scale up primary health care (PHC) alone could prevent more than 60 million deaths in the period from 2020 to 2030, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). WHO-supported vaccination campaigns have eradicated smallpox, driven polio to the brink of elimination, and prevented millions of child deaths. Economically, strengthening primary health care offers substantial benefits by boosting productivity and reducing long-term health costs—some estimates forecast a return of up to $16 for every $1 invested.

Despite these achievements, WHO faces a dual crisis: deep financial cuts—its 2026–27 budget reduced by more than $1 billion—and an erosion of political support, exemplified by the withdrawal of U.S. funding and membership. These setbacks jeopardize not only global coordination during pandemics but also long-term development strategies in regions such as Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC), where national institutions are often fragile and politically volatile.

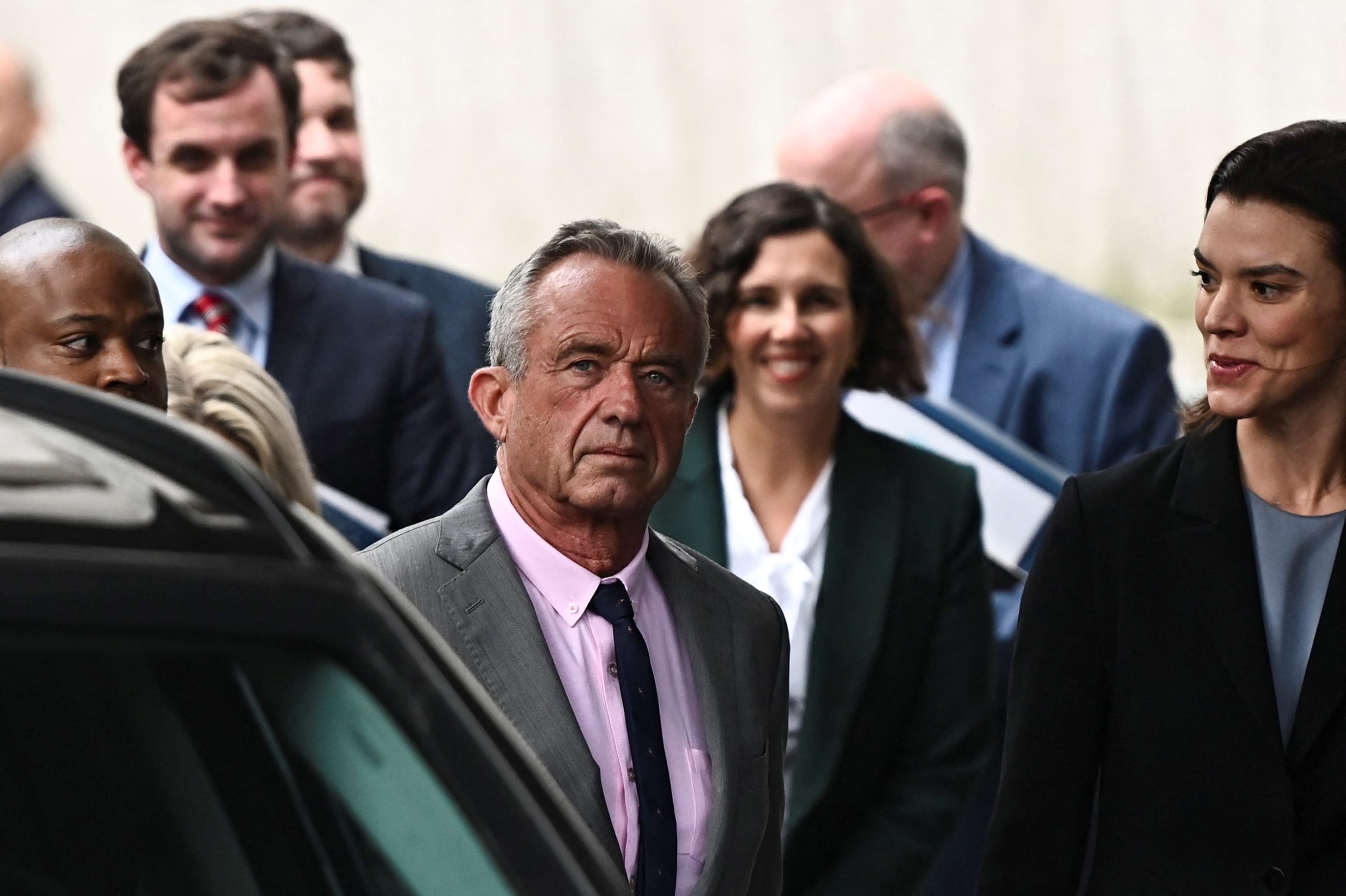

As global leaders gather at this week's UN General Assembly in New York City to debate the future of multilateral cooperation, the financing of international institutions, and the solutions to the increasing burden of noncommunicable diseases, this article outlines three interconnected points on the urgent need for global health investment in Latin America:

- The critical role that the WHO and its regional office, the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), play in sustaining public health systems in LAC.

- The importance of primary health care as a driver of equitable human development.

- Why the weakening of global health governance threatens both fundamental human rights and economic efficiency.

Multilateralism as a Public Good: Global Norms and Shared Gains

The WHO serves as more than a technical advisor. It builds consensus around global health norms—such as routine vaccination, disease surveillance, and emergency response—and ensures that these are operationalized across borders. Its role is foundational in generating scientific agreements and fostering standards that poorer nations can adopt, thanks to shared research and data infrastructure.

In Latin America, PAHO plays this consensus bridging role. As both the WHO Regional Office and the specialized health agency of the Inter-American system, it supports 35 member states. Through mechanisms such as the Revolving Fund for Access to Vaccines and medicine procurement, PAHO purchased 224 million vaccine doses in 2024, strengthening national immunization programs across the region. That year alone, PAHO further supported Belize, Jamaica, and Saint Vincent and the Grenadines in achieving elimination of mother-to-child transmission of HIV and syphilis, and Brazil was recognized for eliminating lymphatic filariasis.

These achievements are not only health victories but also governance victories. They reflect decades of sustained regional cooperation across various government administrations in the participating nations. In countries such as Argentina, where governments frequently shift agendas and restructure and replace technical teams after elections, institutions like PAHO function as custodians of institutional memory and guarantors of policy continuity. This capacity to maintain medium- and long-term development strategies is indispensable, especially in contexts when immediate political pressures often override evidence-based planning.

When Symbolism Becomes Substance: The Argentina-United States Alignment

Argentina has historically been a leader in health policy in Latin America, having both robust scientific institutions and deep ties to WHO and PAHO frameworks. However, the recent political realignment under President Javier Milei, who publicly supported the U.S. withdrawal from the WHO and subsequently in May withdrew Argentina from the organization, sends a troubling signal.

This symbolic alignment risks undermining Argentina's credibility as a regional health leader, weakening access to vital technical assistance and funding, and eroding long-term capacity for coordinated, equitable health policy. The cost may not be immediate—but it nevertheless will be profound. As consensus weakens globally, national health agendas risk becoming increasingly politicized and fragmented, especially in countries with limited institutional resilience.

In early September, the United States announced a recission of $45 million to PAHO, citing the use of Cuban health workers through a PAHO program as potential human trafficking of those individuals. As of yet, Argentina does not appear to be withdrawing its funding or support PAHO.

Health as Human Capital: Why Primary Care Is a Smart Investment

Health is more than a service—it is a core enabler of human development. Without access to quality health services, especially at the primary level, individuals cannot pursue education, access labor markets, or live lives they value—a central tenet of the Nobel laureate economist and philosopher Amartya Sen's human development approach.

Health is more than a service—it is a core enabler of human development

LAC remains the most unequal and violent region in the world. Despite having only 8% of the global population, the region experienced one of the highest COVID-19 death rates per capita, according to WHO data. The pandemic revealed and amplified existing vulnerabilities. In middle-income countries such as Argentina, where informality and inequality are high, and public investment often fluctuates, PHC is a vital equalizer. Establishing universal health coverage through PHC has been estimated to prevent 8.6 million excess deaths annually. Yet the symbolic and financial weakening of the WHO undermines national advocacy for PHC investments. Without a strong global standard-setter, domestic policies risk deprioritizing PHC in favor of visible, immediate health interventions.

Health Investment Is a Rights-Based and Economic Imperative

The weakening of the WHO poses a dual human rights and economic threat to society. From a human rights perspective, it undermines equitable access to essential services for the world's most vulnerable. When global health governance falters, it is the poorest who suffer most—from missed vaccinations to unchecked epidemics. From an economic perspective, it erodes one of the most efficient tools for inclusive development. Few investments rival primary health care in terms of cost-effectiveness and returns for society.

The real cost of U.S. withdrawal and multilateral retreat is not just in dollars—it is in deaths, lost opportunities, and the long-term degradation of human capital in countries that can least afford it. For Latin America and countries such as Argentina, preserving the integrity of the WHO and PAHO is not optional but a strategic necessity. If we fail to uphold these institutions, we risk entrenching inequality and sacrificing the very foundations of human development for generations to come.