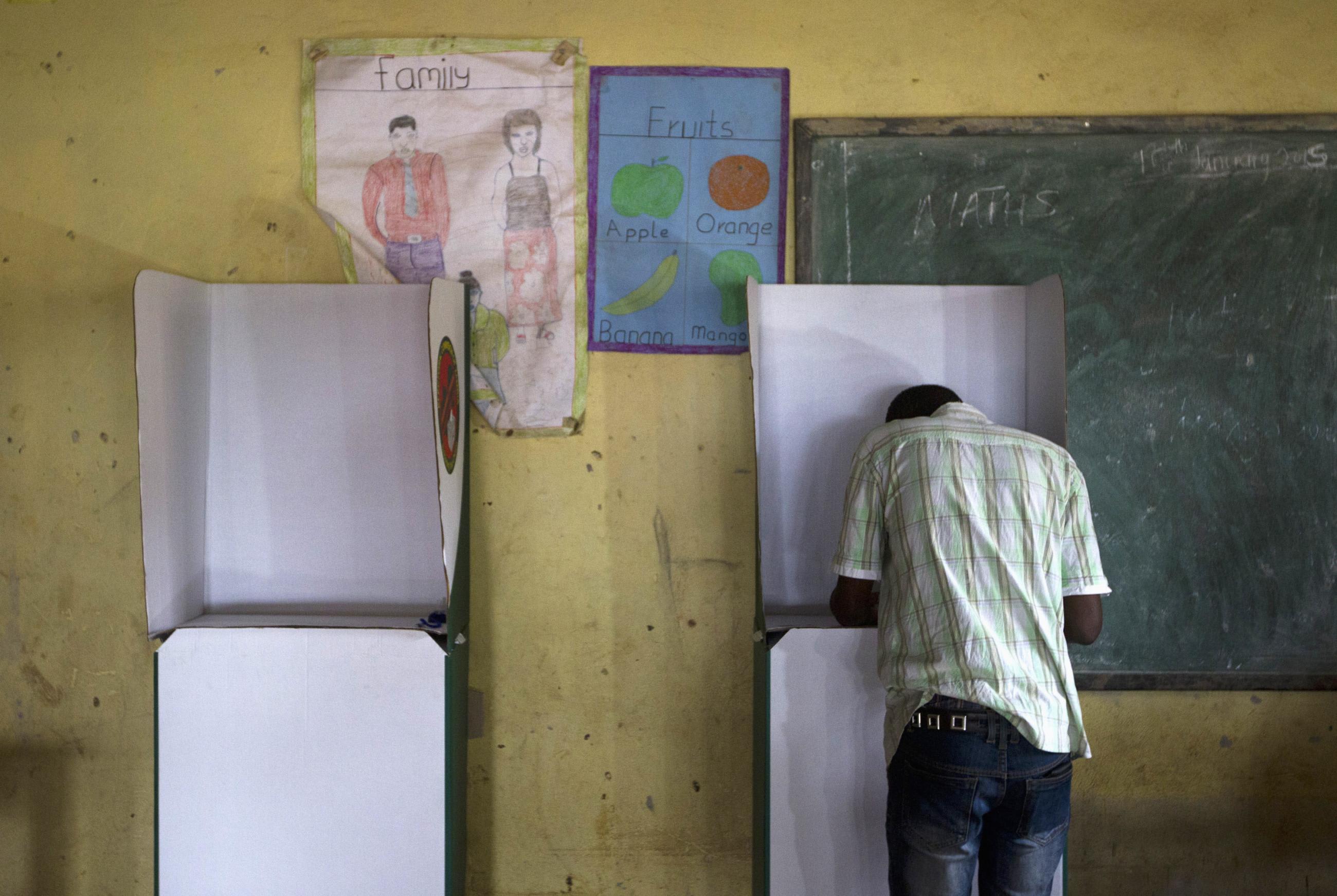

Each year, road traffic crashes in Zambia kill more than three thousand people and injure fifteen thousand others. In 2018, after a series of crashes injured or killed a dozen children on their daily walk to and from Northmead Primary School in the country's capital of Lusaka, the city improved infrastructure in the surrounding areas, including crosswalks, textured rumble strips, footpaths, and new signage. Then, in 2022, the city mandated a speed limit of thirty kilometers per hour in school zones and began installing signage cross the metropolitan area.

The local leader behind the effort is Chilando Chitangala, who got involved as deputy mayor and then was elected mayor in 2021. She spoke about her work with Think Global Health.

□ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □

Think Global Health: What's your professional background? Were you born and raised in Lusaka?

Chilando Chitangala: I was born in Lusaka, so this is my hometown. I love to live here because it's all I know. My family is from here. I went to primary school and secondary school right here. I also went to University of Lusaka. I have an executive MBA in leadership and wealth creation.

I'm a businesswoman—have done business for twenty-five years—and known by my city as a business person. Doing civic work really is simply my passion. I want to work with people. I want to improve my city. I want to clean my city. I want to plant trees. I want to make my city green. It's a passion because this is really my hometown.

Think Global Health: How has the city changed over your lifetime?

Chilando Chitangala: When I was growing up, it was green and very clean. It was called a garden city because we had a lot of trees, a lot of flowers. We had dust bins outside our houses. Waste management was done properly. The local authorities were really up to date with issues.

Being a councillor means that you're the best communicator between the people and local governments.

Chilando Chitangala

I was always the critic out there. I always complained. Why has the council have not done this? Why is the city looking like this? So, I thought, "okay, how do I get into the council?" I had to use a political approach and path. That is how I started planning my journey.

I've enjoyed the journey because being a councillor means that you're the best communicator between the people and local governments.

A lot of urbanization is under way in the city. All of a sudden, a city that was [once] about a million people is now more than three million. It's just not locals who are coming to the capital. It's also people from neighboring countries, for economic survival.

Unfortunately, our waste management is not really up to date. The communities are managing because we have people we work with in the community who collect garbage. We've also tried to educate communities and people on how to keep the city clean, how to manage the waste.

The challenge in the central business district, though, is a big one. We are prone to waterborne diseases such as cholera. We haven't had an outbreak as bad as the one in 2018, but it is still a problem. Right now, Lusaka itself doesn't have cholera at all, but in the eastern part of Zambia it is an issue.

Think Global Health: What are the biggest priorities for you as mayor?

Chilando Chitangala: My biggest goal is to take Lusaka back to what it used to be — a green and clean city. Even if I tell [people] about good service delivery, if I don't do the very little things that are visible — making sure that we plant trees, making sure we have some flowers around, litter is picked [up], some dust bins around — people will not be happy. When they see something visible — a clean city with dust bins around, they can throw their litter in a bin, they can go into town and feel secure, they can find parking, they don't have to be disturbed by traders — I think that will be a good thing. One of my goals is to have markets built, maybe two more big markets to accommodate all these traders that are in the city.

Think Global Health: What put road safety on your radar?

Chilando Chitangala: As a city, we didn't have pedestrian crossings for people and children to cross safely for a long time. Working with [the Partnership for Healthy Cities], we've made sure that the local authority [makes] sure that most of the schools in the city have a pedestrian crossing, painted on the road just by the school. We work with government to reduce traffic speed. We have humps to slow [traffic] down, and then [drivers] have to reduce the speed [to between] thirty and forty kilometers per hour. So that was a very big plus. It reduces accidents.

Think Global Health: Have the rates of pedestrian or road traffic injuries been increasing over time?

Chilando Chitangala: At one time, we had a high number of traffic accidents. We still do, in fact.

The police mount cameras around the city to make sure that motorists slow down.

We've also put up signposts that tell us how fast you are allowed to drive on that particular road. On some roads, such as near schools, the limit is between thirty and forty kilometers per hour. On others, it's sixty kilometers per hour. On most of the roads in Lusaka, though, the limit is eighty kilometers. It's very rare that more than one hundred kilometers per hour is permitted. So that is controlled.

Then in one of our biggest bus stops, when long-distance busses are going out of town, road traffic police will check the driver, use breathalyzers to make sure that they don't drink alcohol while driving. Alcohol is one of the biggest problems we have . . . people drinking and driving. But you know, with a lot of sensitization, you can begin to reduce that. The police will always have a breathalyzer to test drivers, which can be — is, actually — a deterrent.

Think Global Health: Are there obstacles to achieving the traffic safety that you would like?

Chilando Chitangala: Yes, there are certainly obstacles. I haven't achieved what I would like to achieve. Drunk driving is one of the biggest problems. We need to work on that. Another is to make sure that [people] driving public transport [are] fully licensed in a proper way. Those are some of the challenges we're still facing. They are why we haven't cut the number of bad road accidents.

Drunk driving is one of the biggest problems. We need to work on that.

Chilando Chitangala

Think Global Health: Is the mayor of Lusaka able to make big changes in the way that the city operates?

Chilando Chitangala: There are some limitations. Finances are a challenge because we don't have good revenue source in the council. So we usually ask for support from partners. We mostly depend on stakeholders, in fact.

Think Global Health: What does stakeholders mean in this case?

Chilando Chitangala: For example, we can work with a business that supports road safety for children, or an organization that supports road safety. Also, we do receive support from [the national] government and the Ministry of Health because they are also concerned.

Think Global Health: To be a mayor who is working with partners globally, does it ever interfere with running the city for your local constituents?

Chilando Chitangala: I have to choose what priorities are for the city. For example, I will follow Vital Strategies because I'm concerned about public health. I would very much like support on road safety, especially [for] school-going children.

They are going to support us with bicycle lanes and walkways. Isn't that fantastic? I'm also concerned about fighting climate change, and would like people who drive to ride bicycles instead, or people that can't afford cars to ride into the city center. You can actually create parking for bicycles right in the central business district. I look forward to that.

I try not to stay away for a long time. A week is enough.

Think Global Health: What do partners bring to the table?

Chilando Chitangala: Some resources and also capacity-building. Capacity-building is important as well.

Think Global Health: You mentioned cholera, and that malaria is still a problem. How do you make the case for working on issues like road traffic when these urgent infectious diseases are a problem?

Chilando Chitangala: We had tried to fight malaria in the past few years, but the numbers have gone up a bit, probably because we haven't sprayed the city for a long time. We have what we call open ponds that are big breeders of mosquitos, which carry malaria larvae. Between April and July, we do door-to-door residual spraying in homes, but we have never really managed to treat the entire city because we need to buy the treatment and sometimes we run out of it. We do have some mining companies that come on board and make the donations.

For cholera, the biggest problem is waste management. Because we have unplanned settlements, we have a challenge with water. In some of the peri-urban areas, they dig holes and use the ground water for bathing, sometimes even cooking, and that that contributes to the cholera challenges.

Think Global Health: Does this make it challenging to focus on roads?

Chilando Chitangala: Not really. Whenever we're doing programs for road safety, we don't forget about the other programs we have under way.

Think Global Health: What are some of the changes a visitors would be able to see that are related to the road safety?

Chilando Chitangala: We've had what we call a Saturday congesting, where we have a lot of new roads built and about four or five big bridges built. The road network has also been supported by the national government. In the last ten years, the city has really developed. We have a good road network in the central business district, but we still need proper inner roads. Most of them are just graded, but the primary roads are tarmac.

Think Global Health: That's good for the motorists—you can travel quicker and more comfortably. Does it make it less safe for pedestrians?

Chilando Chitangala: Yes, it makes it less safe for pedestrians because people get excited. But it's also important to make sure that we have signage there to control that someone can't drive more than sixty kilometers per hour on this road, forty kilometers on this road, maximum eighty kilometers per hour on this road. Signage is very important.

Think Global Health: What do you see as the advantages of having a higher profile globally around these issues? How does that affect your political prospects?

Chilando Chitangala: The people see that they voted for a person that cares for them, a person who is bringing progress to the city. They must get to know what we're doing, as their local leaders, for them. That's very important. If we don't feed them the information then they won't understand or want to know what we can do and can't do. Media is an essential tool for politicians.

Think Global Health: Are there other mayors around the world who you particularly admire, or feel like Lusaka can learn from and emulate?

Chilando Chitangala: I like the mayor of Freetown, Yvonne Aki-Sawyerr. We chat every once in a while. She's one of those mayors who have inspired me to work hard and be focused. Because she is from Africa, the problems are similar. Our solutions are similar. Even the mayor of Banjul, in Gambia, [Rohey Malick Lowe]. She's the first female mayor of Banjul, and we exchange notes. I also trained with the mayor of Los Angeles, Karen Bass. I'm learning a great deal from these people and others like them. They're mostly women, can you imagine?

I haven't stopped doing my business. I think it's important . . . . because I have my own backbone. I can make my own money.

Think Global Health: What kind of business?

Chilando Chitangala: The fashion industry. I run two boutiques.

Think Global Health: Looking ahead, what important next steps do you foresee?

Chilando Chitangala: [Mayors] in the United States and in Europe have their own budgets and a lot of power. Whereas here, in my country, I am required to report to the central government and decisions are not made easily. I would like to move to a position where I can make frequent decisions for the people. I am looking forward to having such a position in the future.

Think Global Health: What kind of position?

Chilando Chitangala: I have big dreams. You may just be invited for my inauguration in the next few years. A big inauguration. We haven't had our first female president, so you never know!

EDITOR'S NOTE: This interview was conducted via Zoom and has been edited for length and clarity.