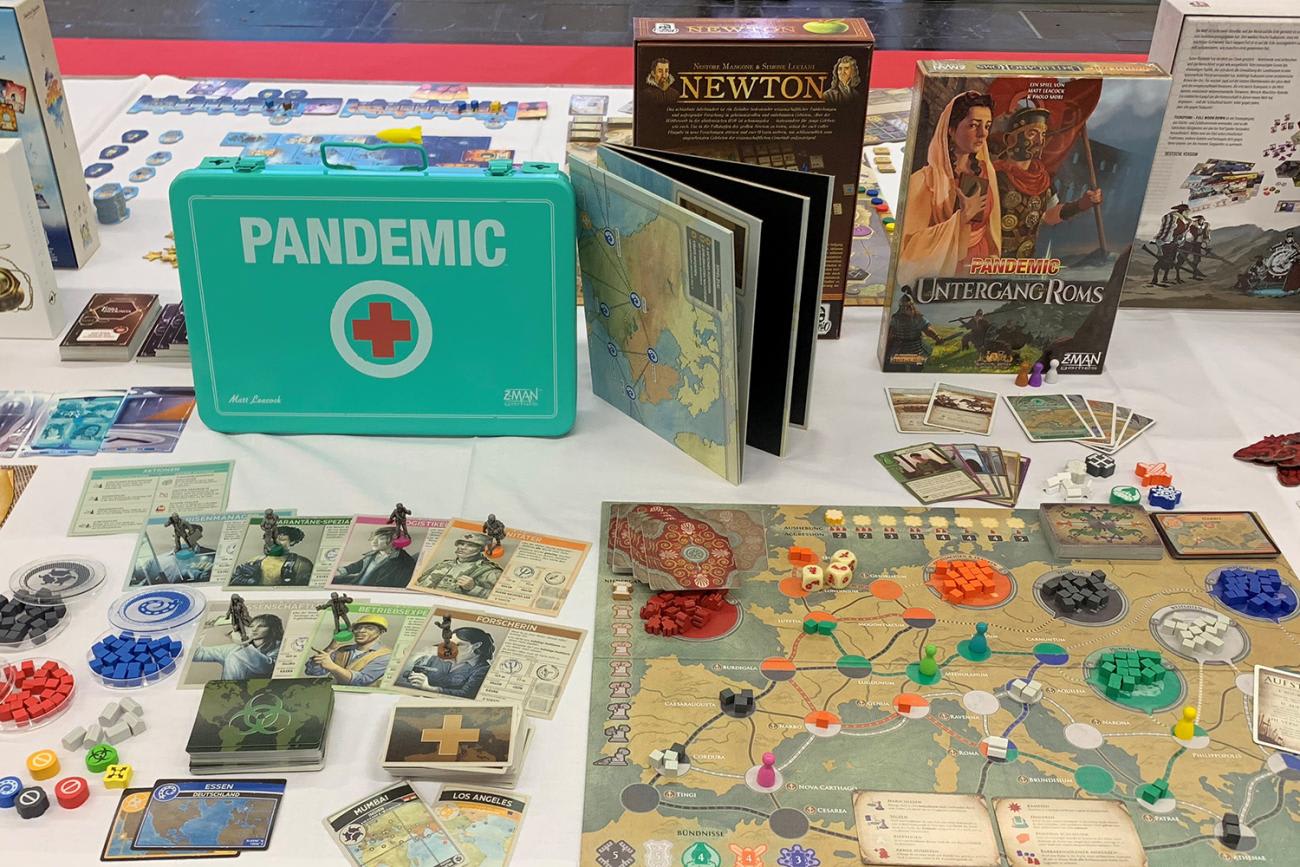

Just like many who work in this field, the editors at Think Global Health have played a board game many times that first appeared a decade ago called Pandemic (from Z-Man Games). It pits a team of players against deadly diseases worldwide, and it's an unusual game—not only because it focuses on global health, allowing players take on roles like scientist, medic, archivist, contingency planner, and quarantine specialist—but also because it uses cooperative play. In the decade since it first appeared, the game's success has spurred three expansion sets, multiple "Legacy" spin-off sets, which have received their own acclaim, a card version, a dice version, a newly-released 10th anniversary special edition set, and a soon-to-be-released novel adaptation. Hoping to understand the origins of this phenomenon, we interviewed game designer Matt Leacock, who created Pandemic, to discuss the game's inspiration, its reception in the global health and gaming communities, and the challenges in designing a cooperative game.

THINK GLOBAL HEALTH: Tell me about your professional background. What led you to design this game?

LEACOCK: I was trained as a graphic designer [and] worked as a graphic designer for a couple of years in Chicago. Shortly after that I came out to California to work as an interaction designer. I worked at Apple and then worked at a lot of the early internet companies like Netscape, AOL, Yahoo, and so on—doing interaction design and user experience design.

But all along that time I was a hobbyist game designer and game player, for sure. And I'd really been tinkering with games—changing them and coming up with my own since I was a kid—all the while just trying to come up with a game that I could eventually get published. So I never really thought of doing it as a living. I just really tried to see if maybe someday I would be able to get one of my games on the market.

The success of that game really opened up a lot of doors, and eventually game design became my career

And I just had a breakthrough with Pandemic. I had done some board games myself. I had run some off my—[LAUGHS]—my printer in my house, ran off like a couple of hundred of them to sell, and tried doing self-publishing for a while. I didn't get very far with that. But I did meet a lot of people attempting to do that who helped mentor me, and after three years of development on Pandemic, I specifically had a game that a lot of publishers were interested in. And the success of that game really opened up a lot of doors, and eventually game design became my career.

THINK GLOBAL HEALTH: Where did you get the idea to focus on infectious disease control and epidemic outbreaks in different countries?

LEACOCK: Yeah, I think there's a number of things that kind of played into the design of that game and the idea behind it. I think first and foremost, actually, the idea to try to do a cooperative game was very much in my mind. I wanted to come up with a game that I could play with my wife and we'd both really enjoy, whether one of us won or lost.

I had played negotiation games with her in the past, and they can get kind of contentious, and you win the game but feel terrible. We noticed that when we played a game called Lord of the Rings. We both really enjoyed the game but it was very tense no matter who won.

I [wanted] to make a cooperative game, and disease pandemics were very much in the news at the time

So I thought, well, I want to try to make a cooperative game, and disease pandemics were very much in the news at the time—I think it was SARS or bird flu at the time—just always in the news. And I thought, wow! You know—microbes and diseases—these things would be really interesting to model and would make a really fantastic enemy because if it's a disease, it's hard to root for them. And they're scary, and they can take over. They can really infect tons of people. I was also really into the idea of emergent behavior, and chain reactions, and viral spread, and so on. So I thought, well, this would make a great bad guy, a great antagonist for a cooperative game.

THINK GLOBAL HEALTH: Were you specifically trying to impart any educational lessons, or was this just about fun game play?

LEACOCK: Early on I was looking at that to see to what extent do I want to bake in an education component. And it turned out—I mean, after you play a game and observe people playing a game over and over again, year after year, it becomes really evident what people are into, and I didn't want to turn people off with an educational component that felt kind of taped on. So initially I was thinking the different player cards could have facts about viral spread or hand washing—different things that could increase the educational component.

But really, the play is the thing, and making the engaging experience was my number one priority. And I found that it pulled people into it, and they forgave any inconsistencies. You know, they weren't really looking for a simulation. They were looking for a great time. And if it taught them a little something along the way, that was great, but that wasn't my primary objective.

THINK GLOBAL HEALTH: What sort of feedback have you gotten from experts who have played—people who really do this for a living?

It's been really positively received by the community. That's been very encouraging for me.

LEACOCK: I heard they had it at the gift shop at the CDC. I've heard from epidemiologists out in the field. It's got a lot of fans in that community. And fortunately as far as I know there aren't any [groaners] in the game—you know, things that are grossly misrepresentative. I think everybody understands it's to some extent a work of fantasy. But at the same time, it does show the gravity of a pandemic. It also shows how you need to cooperate in order to work together to fight the disease—and models some spread as well. It's been really positively received by the community. That's been very encouraging for me.

THINK GLOBAL HEALTH: What about general fans, people who are younger or people who are approaching it just as a game and not from the perspective of a professional in the field?

LEACOCK: It's been overwhelming. I mean, that's just been super gratifying. One of the things I hear more than anything is that this is the game that brought me into the hobby. A lot of people view this as like a gateway. They discover a whole new world of board games after they play it. They play it and have such a good experience that they go out and check out other games.

There's a big renaissance in board gaming right now. The hobby has grown phenomenally over the past ten years in ways that nobody really could have expected, given how many digital games are out there right now. So I've been really gratified to hear how many people really enjoy Pandemic and go seek out other games like it. And the cooperative aspect has been a big thing as well, so probably the most gratifying thing is hearing people say that the game brought them closer to their spouse because they play it together, and at the end of the game they have a great experience whether they won or lost, and they can really work together, do a lot of communication with each other.

THINK GLOBAL HEALTH: Can you comment a little bit more about this renaissance in board games. Is it about new board games or retro board games we grew up playing?

LEACOCK: I think that you could look at the emergence of a game called Catan that came out in 1995. A lot of newer games that came in from Europe just had a higher quality. They involved all the players till the very end, had reasonable play lengths so you can generally finish them in forty-five to sixty minutes, and kept everybody involved—a lot of interaction, and so on. So those began to catch on, and I think a lot of new designers played them and got excited by them.

Also, the internet came on the scene, and it's much easier to find communities of players and to learn what the good games are. And I think lately with Kickstarter and Crowdfunding, just about anybody can be a game designer now, so there's been this explosive growth in the number of titles—thousands of games coming out every year now.

THINK GLOBAL HEALTH: What were the challenges in designing Pandemic and bringing it to market.

LEACOCK: This is the first published game I ever did, so I didn't have a ton of experience. But I did spend a lot of time on it, so what I lacked in experience I made up for in testing. I tested the game on a lot of people—co-workers, colleagues, other game-playing experts—and just did many, many iterations of it.

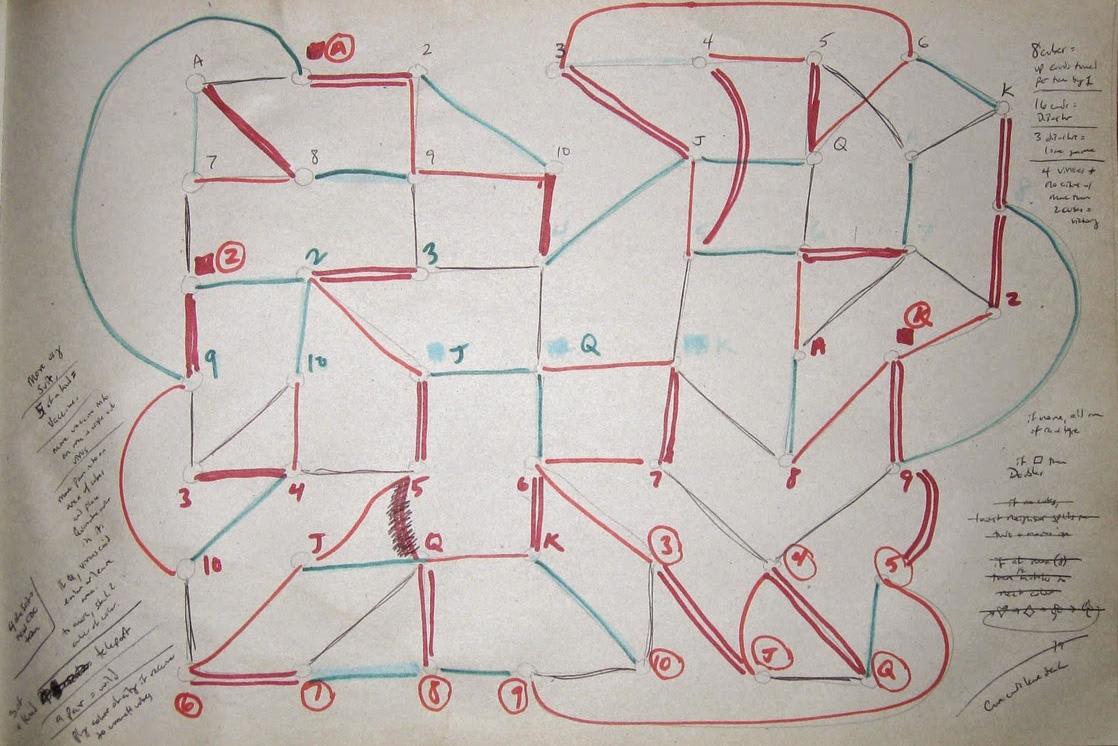

The core challenge was really trying to make the game simple enough to play while still being really engaging and scary. I came up with the initial invention—the way the game models the different hot spots of the world getting re-infected—really early on, just kind of bumped into that by accident and saw how that could be very exciting. And then I struggled for the next few years just trying to figure out [how] to patch that up into a playable product. So it took a while to actually kind of nail that, but I was glad I was as persistent as I was.

THINK GLOBAL HEALTH: You mentioned "hot spots," which in your game are cities. How did you chose those urban hot spots?

LEACOCK: Yeah, for picking the cities—basically knowing what I knew at the time—I was looking for really, really large metropolitan areas.

I tested the game on a lot of people—co-workers, colleagues, other game-playing experts

So I looked at the largest spots around the world, where most people were, and I looked at the population of the city as well, with the assumption that this is where the biggest outbreaks, the most deadly outbreaks might happen. And then I adjusted that based on trying to give the world a good texture. I didn't want to leave out Australia completely even though Sydney doesn't have a tremendously large population. I also tried to spread it out a bit. Otherwise, I think all the major population centers being in India and China, it would have been kind of a lopsided world if I only used that as a single filter. So a fair amount of experimentation went into that, trying to find something that made sense from a thematic point of view but also was playable and evocative.

THINK GLOBAL HEALTH: Has your thinking at all changed in terms of global health and disease?

LEACOCK: I think part of it is that I've just been encouraged by how many people in the field have reached out and been so excited about it. I think the themes of cooperation globally resonates with people, and they see the experience as positive. And also, I think people enjoy kind of a break from some of the more tired subjects of board games and are happy about the opportunity to try out something new and role play, for example, being a disease fighter in the world. And I think it has opened up people's eyes as to how you could create games to model things like this, whether it's spreading disease, or potentially, you know, modeling the climate crisis, or other ways where people need to cooperate against a really wicked problem.

THINK GLOBAL HEALTH: Why is cooperation important in the world and in game play?

LEACOCK: Well, I think it's really interesting that, for so many years, competitive gaming has been almost synonymous with gaming. I mean, people think that that's what gaming is, and the reality, though, is that humans cooperate all day long. It's almost our default way of interacting with each other, that we're all trying to work together most of the time… it's kind of unexplored space.

THINK GLOBAL HEALTH: What you are saying is true of drama as well. In literature, plays, and movies, conflict is almost synonymous with narrative structure.

LEACOCK: Yeah, I think that's right in that it creates interest. But it's not necessarily an indicator of what everyday life is like. I mean, there's plenty of conflict in the world, plenty of challenges to be overcome, but that doesn't necessarily mean they have to be zero sum or competitive with other humans.

…how to overcome the challenges of the real world in the sandbox environment of the game

So what I think is great about cooperative games is that many times they are man versus environment, you know. They can be [about] a group of people trying to overcome a challenge, which is outside of the people, where the players are banding together and learning how to come up with creative solutions to problems that are present by the game itself. And I think we see plenty of that in the world right now, but there aren't as many games that are modeling that. I kind of stumbled into it, and I've seen that there can be a whole genre of games that tackle that, and I think basically there's big demand for it, as well, just because they help—they help people learn about—in a playful, safe way—how to overcome the challenges of the real world in the sandbox environment of the game.