About one-third of the world's population is overweight or obese, and 62 percent of those individuals live in low- and middle-income countries. As childhood overweight and obesity cases have emerged in developing nations at a rate that is 30 percent higher than in developed countries. An endless supply of junk food, unfettered access to the internet, smart phones, and a waning culture of physical activity have engendered a situation where, more than ever, youth are inactive and gaining weight. In the emerging economies of Brazil, India, and Mexico, governments have aggressively responded through a phalanx of public health measures, ranging from a soda tax to improved food labels and advertising regulations.

Understanding who is at fault for rising obesity is complex. Many have pointed the finger at major soda and ultra-processed food companies. They, however, are only partly to blame. As I discuss in my new book, Junk Food Politics, in today's emerging economies, aspiring political leaders have indirectly contributed to this troublesome situation by partnering with those companies to achieve politically popular anti-hunger and economic campaigns. These partnerships legitimize soda and ultra-processed food companies and send the wrong message to the public.

There is a way forward. Political figures can improve health outcomes by questioning the efficacy of policy partnerships and overcoming their fears of potential food-industry retaliation, such as a withdrawal of political support. Incorporating civil society's voice and influence in government will also improve children's health.

About one-third of the world's population is overweight or obese

Questionable Policy Partnerships

In a context of economic growth and inequality, presidents in several emerging economies have worked with the food industry to help achieve their broader goals of eradicating poverty and hunger, and improving job security.

In Brazil, during President Luiz Inácio "Lula" da Silva's first two terms in office (2003-2010), he showcased his commitment to eliminating hunger and reducing poverty through the Fome Zero (Zero Hunger) program which supported families through diverse strategies including increased employment and ensuring a decent minimum wage, while upholding the normative principle of access to food as a human right. As part of Fome Zero, the Bolsa Familia cash transfer initiative improved low-income families' access to food and health care by requiring that recipients ensure their children receive regular primary care checkups, immunizations, and school attendance. Similarly, from 2012 to 2018, Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto was committed to eradicating hunger through his National Crusade Against Hunger campaign. Both presidents' success benefited from their partnerships with major food companies, including Nestle, which supported their programs and provide employment opportunities.

Political leaders have also partnered with major corporations to achieve economic gains. In September 2019, India's Prime Minister, Narendra Modi, delivered a keynote speech and met with company executives at the Bloomberg Global Business Forum in New York City. At this event, Modi encouraged investments from Coca-Cola, Bank of America, Shell, and IBM, and highlighted India's auspicious democratic context for foreign investment. Modi, at one point, also requested that major soft drink producers, including PepsiCo, include more fresh fruits in their products to help struggling farmers. PepsiCo's then-CEO, Indra Nooyi, agreed to work with Modi to help farmers and achieve his broader development goals.

While Brazil and India's leaders should be commended for their admirable social and economic policy endeavors, their partnerships with food-industry giants legitimize soda and ultra-processed food companies. This can severely complicate efforts to help reduce public demand for unhealthy food products, especially among children and low-income communities.

Addressing the Situation

As leaders with considerable influence, presidents should question how partnerships with major food companies contribute to the junk food industry's legitimacy, the popularity of their foods, and what it means for children's health.

If presidents and other political leaders want to avoid those partnerships, they should overcome their fears of distancing themselves from powerful businesses. But this can be difficult to achieve.

Consider Mexico's current president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, commonly referred to by his initials, "AMLO". Hailing from the leftist political party, Morena, AMLO emerged into office with a commitment to reducing poverty, violence, corruption, and malnutrition. Despite vocalizing his support for improving nutrition and children's health and warning of the dangers of processed foods, he met with Coca-Cola's CEO, John Quincey, to discuss investments, small business support, taxes, and even nutrition policy.

But if AMLO was fully committed to tackling obesity and issuing these public warnings, why did he meet with Coca-Cola's CEO? Was he afraid of ostracizing such a politically powerful company?

Perhaps. Coca-Cola has a long history in Mexico. For years, the beverage company benefited from President Vincente Fox, a former Coca-Cola chief executive for Latin America who strengthened the company's connections with policymakers. In addition to being the most consumed soda product in Mexico, Coca-Cola has also been used in Indigenous religious ceremonies and is perceived by some Indigenous healers as having healing powers within these communities. In this context, it becomes challenging to break ties with the soda giant.

The failure to reduce obesity is not due to individual willpower, but to the absence of political will to take on the power of major food corporations

Margaret Chan, director, WHO

Breaking with the precedent set by his predecessors, AMLO recently stated that consuming Coca-Cola is bad for your health. At the same time, government health officials have questioned why the public needs soda. This move signals to many that the Mexican government is committed to safeguarding children's health.

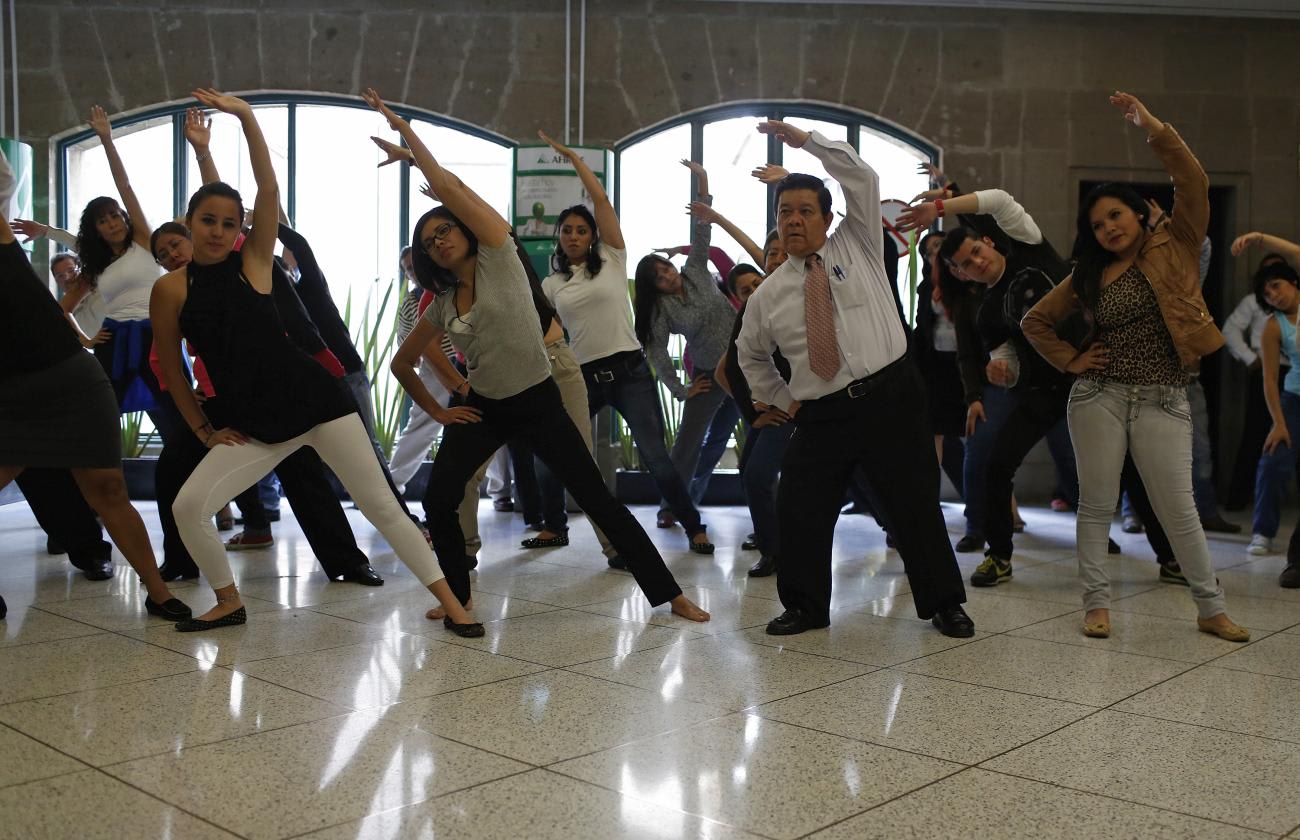

Beyond public statements, heads of state can strengthen the activist and research community's presence within policymaking institutions. In Mexico, Brazil, China, and India, the food industry has had a strong presence in drafting nutrition and childhood obesity policy for national agencies and committees, in turn securing industry policy interests. Research by Susan Greenhalgh at Harvard revealed that the industry-backed International Life Sciences Institute (ILSI) worked to get the Chinese government to prioritize the importance of exercise in reducing childhood obesity.

On the contrary, activists and researchers have never had nearly as much representation and support in policymaking institutions. Government leaders should now work with agency directors to ensure that society's presence and voice when compared to the food industry's is equally as, if not more, represented.

Rebuilding these participatory policymaking institutions is also important. In Brazil, during Lula's first tenure, nutrition activists, and researchers had a seat at the policymaking table through the National Council of Food and Nutrition Security (CONSEA). CONSEA had direct access to the office of the presidency and was committed to establishing anti-hunger and nutrition policies, such as ensuring children's access to healthy meals in schools. However, this council was subsequently disbanded under the conservative Jair Bolsonaro presidential administration (2019-2023). Re-elected into office this year, Lula appears to have reconstituted the CONSEA, and with this, rejuvenated the government's preexisting commitment to anti-hunger, improved nutrition, and children's health.

Going Forward

In countries where heads of state wield considerable authority, they are in a strong position to dramatically improve their government's commitment to reducing childhood obesity. As former World Health Organization Director Margaret Chan argued in 2016, the failure to reduce obesity is not due to individual willpower, but to the absence of political will to take on the power of major food corporations.

Establishing political will to counter the influence of major food corporations requires reconsidering public-private partnerships with major soda and ultra-processed food companies, overcoming fears of industry retaliation, and increasing civil society's policy influence.

Going forward, if presidents seek to establish policy partnerships, then their wisest move will be partnering with activists, academic researchers, and community leaders who truly care about children's health.