Hoping to learn more about both the basic science of coronaviruses and the clinical outlook, Think Global Health contacted Stanley Perlman, a professor of Microbiology, Immunology, and Pediatrics at the University of Iowa's Roy J. and Lucille A. Carver College of Medicine, who has been studying this type of virus for nearly forty years. He discussed what we know and what we don't about their treatment, spread, animal origins, their ability to mutate, and their overall threat to global health.

Think Global Health: As a physician, what would you say to patients to calm fears?

PERLMAN: I stopped seeing patients about, oh, thirteen years ago now, but I think in general what you have to do is you have to—I think what one does is point out the risks and what one can do to minimize any chance of getting an infection like this. In general what that means is if you wash your hands you're going to be protected from transmitting it to yourself, because it often ends up on your hands and then people are always putting their hands to their face. So if you don't do that or you wash your hands, that's the first thing.

The more epidemiology that we know, the more we're going to be able to figure out how big a deal this is in terms of spread

Second thing is if people are sick they should actually not be in public. That's more incumbent on the person who is ill rather than you as a person being exposed to it. So I think if I had a patient in my office who was worried about this, I would encourage him to avoid being around people who are sick. It's really unlikely that you'd run across somebody with this illness—for example on the bus or the train or in a public area—but just like with any other contagious virus, like flu, you have to do your best to not be infected. And right now we know that this virus spreads from person to person. We don't know how well. And we really don't know how infectious it is. We don't know if it's getting more infectious. The SARS virus during the course of the epidemic became more able to infect people than in the beginning.

On the other hand, the MERS coronavirus hasn't really changed at all. So we have those two contrasting ways things could happen. We have to get more information about the virus and the virus sequences. And then the more epidemiology that we know, the more we're going to be able to figure out how big a deal this is in terms of spread.

□ □ □ □ □

Think Global Health: Are we better prepared than we were with SARS or MERS?

PERLMAN: I certainly think better than SARS. MERS is not so clear because I think people knew a lot by the time 2012 rolled around. So I think we're more aware in terms of needing to make sure that people come from areas that could be affected, that we pay attention to them and that we if necessary screen them to see if they're sick. [If] somebody was coming off a plane from Wuhan and had a fever and respiratory disease, I would assume the worst until we could prove otherwise. So people are more aware of this occurring.

But you still get issues. So the only MERS outbreak outside the Arabian Peninsula occurred in Korea, where somebody came back from the Arabian Peninsula, went from hospital to hospital before he was finally seen and diagnosed. But in that time, he infected a lot of people in the different emergency rooms he went to. So there the key thing was he didn't say, Hey, I just came from the Middle East, and they didn't say Where were you traveling? So awareness is a big deal, and people know that they have to jump on this piece of information.

□ □ □ □ □

Think Global Health: How does the virus compare to SARS, MERS, and other coronaviruses?

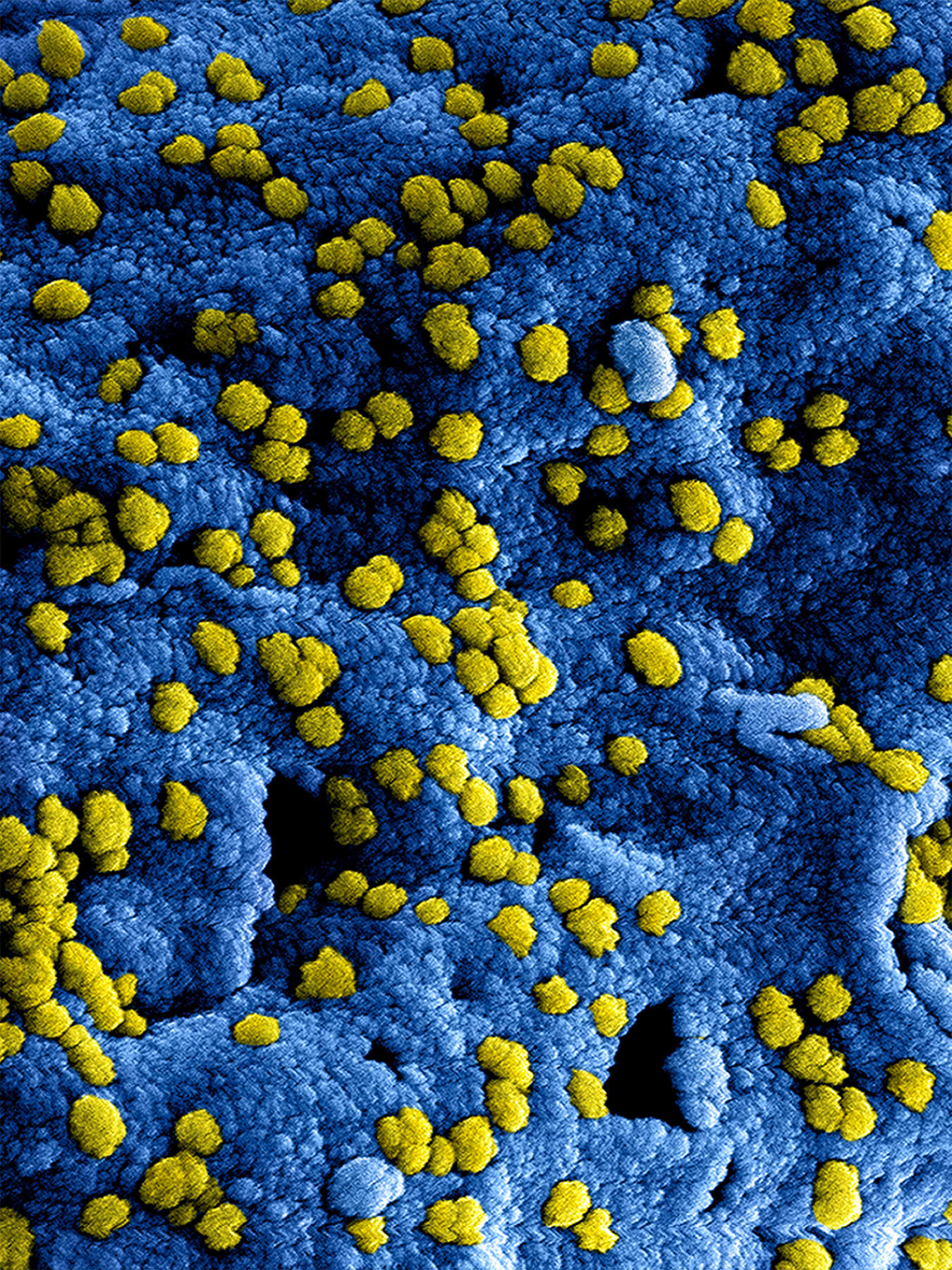

PERLMAN: They all have the same structure, so that's why they're all called coronaviruses. They have different sequences.

There are some bat viruses [with which] it's 85 to 90 percent similar—or identical. I don't even want to say similar—identical

The sequence of this virus is nearer to SARS than it is to MERS. It's maybe 70 percent similar. And then it's even nearer to bat viruses. There are some bat viruses [with which] it's 85 to 90 percent similar—or identical. I don't even want to say similar—identical. So it behaves differently. For a virus to be infectious for humans there are lots of things it has to do, but two main things are it has to have a protein on its surface so it can get into a human cell to infect it. And then it also has to be able to counter any human cell factors that prevent infection. So these are the innate immune-response genes, and they're different from species to species, and a virus, to be successful, has to counter [them].

□ □ □ □ □

Think Global Health: Did the virus come from bats?

PERLMAN: Well, you know, this is a really good question because I think in the end it'll probably turn out to be a bat virus, ultimately. But the question is whether it jumped directly from bats to people or if it went through intermediate hosts. We think that the MERS virus is, ultimately, a bat virus. We now all get it from camels, and camels were infected maybe many, many years ago—if they, indeed, got it directly from a bat. And SARS—it's more similar to a virus we can find in bats. But again, we don't know if it went from bats to people, and it seems more likely that it went in these wet markets in Guangzhou to animals that we normally don't think about—like palm civet cats and raccoon dogs—and then to people. So it adapted a little bit, and it adapted more in humans.

I would bet that ultimately it came from bats, but I don't know how long ago. And in this case it may be very recent because it's at least 85 or 90 percent similar to bat viruses. We don't know for sure which animal, but I would bet for sure it came from an animal that ultimately got it from a bat.

□ □ □ □ □

Think Global Health: What is the standard of care for somebody who contracts this virus? Are there antivirals? Do they use interferon treatment? Do people have to go on respirators?

PERLMAN: During the SARS epidemic, the therapy that was used routinely turned out to be bad—made things worse. So as a physician what you always want to do is help. And sometimes you don't really have choices, so you come up with the best alternatives. And when they've not really been evaluated thoroughly, the best alternatives may be bad. They may make things worse. That's why the FDA exists for things that are not so as acute as this. And you try to figure out whether a drug has value or not, or whether it's harmful.

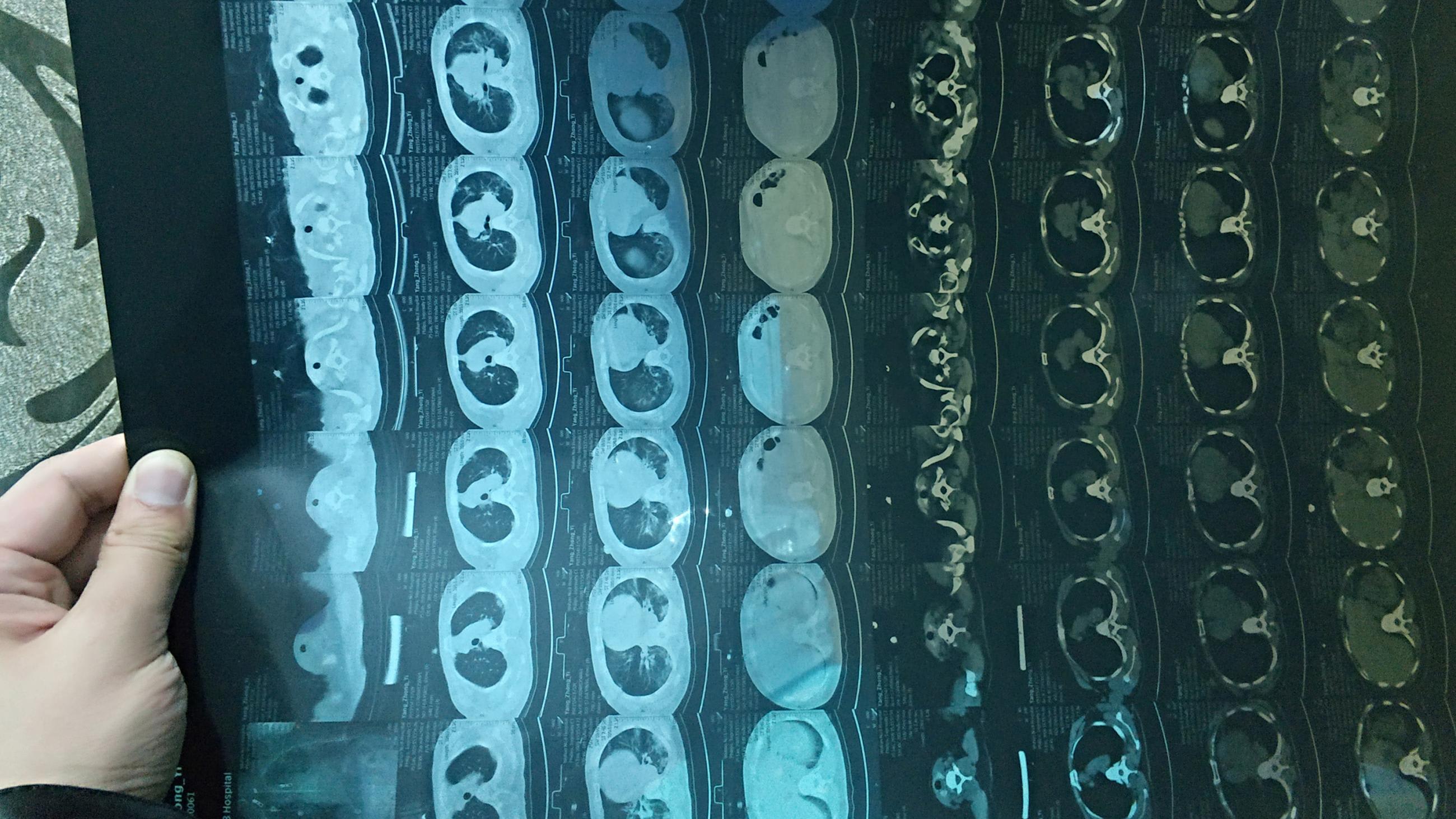

Percent similarity between the new coronavirus and some older bat coronaviruses

There's no antiviral that will work. People may use interferon, but we have, actually, studies in mice that say if you do that at the wrong time you may make things worse rather than better. It's not like it either does nothing or makes things better. It could make things worse. So you make sure that the people are comfortable. You give them as much respiratory support as they need—you wouldn't put somebody on a respirator or a ventilator unless they were sick enough so that they couldn't breathe by themselves. You put them in the proper room for precautions. And you make sure the people who go in there take the proper precautions, so they don't get infected. Because health care facilities are often the main place that infections occur.

□ □ □ □ □

Think Global Health: How long is the incubation period?

PERLMAN: I don't know about this one, of course, but for most coronaviruses it's somewhere around four to ten days—rarely longer than that. So if you're not contagious till you're sick, then you have a little bit of leeway in having to catch everybody immediately. If somebody who's on the plane is incubating the virus, if it's not in his upper airways just sort of trickling down to his lungs, he's not going to be very contagious. Is he zero contagious? No. Probably not. But we don't really know. But with this disease, you are contagious when you are sick—at least, if it's like SARS and MERS. There's a difference between that and flu or measles, where you were contagious just when you were starting to get sick. But this seems to be different.

Because the virus is growing in your lower lungs—at least, if it's like SARS and MERS—it's not really your upper airway. Flu is so infectious because it's in your upper airways. So whenever you sneeze, it's going to be released to and transmitted to other people. If this virus is not in your upper airways, that means it's incubating or starting to grow in your lower airways. And to get something from your lower lungs up to your nose so you can spread it, the virus has to be in large enough quantities to be expelled in a certain way, either by your coughing vigorously or by aerosolization from a procedure in the hospital.

□ □ □ □ □

Think Global Health: How will forces like urbanization, poverty, migration, and trade influence this disease?

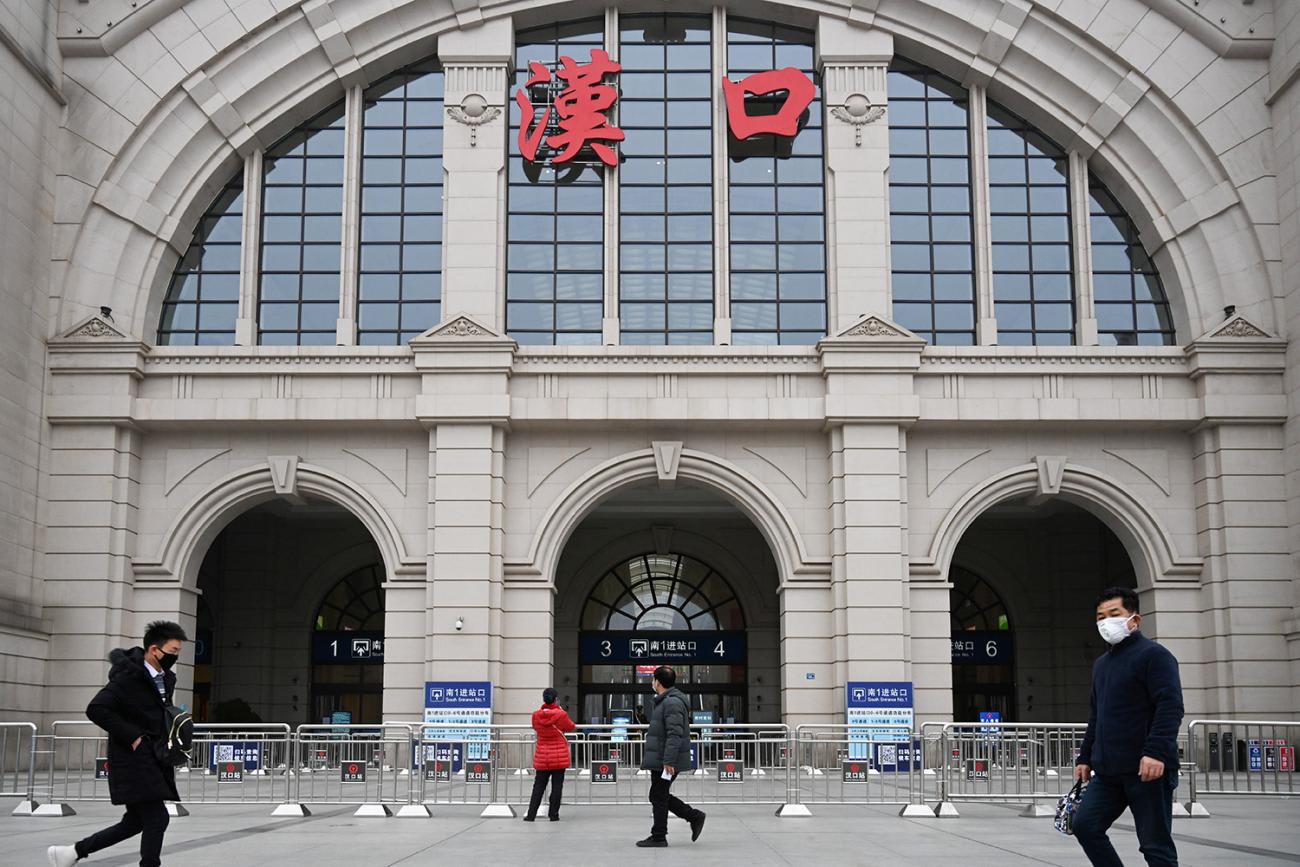

PERLMAN: It's hard to know what the effects on trade would be. We know the SARS epidemic basically shut down cities, whether in Canada or in Southeast Asia and East Asia. Places were shut down. So that, of course, impacted trade and other economic issues.

I don't know if that's either poverty or urbanization. It's almost more like the opposite.

In terms of the urbanization and poverty, it's an interesting question because these wet markets have been around for a long time. I don't know if they're getting more animals that are exotic, like bats from caves. My understanding is actually the government has outlawed this, and a lot of this stuff is done under the table now. So as opposed to the SARS epidemic, when these wet markets were OK, they're not OK now. So I think this is more like rogue merchants, which may be one of the reasons it may be tricky to trace it all down because people might have information, but they might have been doing something they weren't supposed to do. So I don't know if that's either poverty or urbanization. It's almost more like the opposite, because people have more money, they can afford these sources of protein and so there's more desire for them. One of the things is I worry about is we have this outbreak in Wuhan, but are there outbreaks in these little towns around Wuhan that we don't know about? Are the same kind of bats being delivered there—and with less supervision, because they're less under the control of the central government? Hard for me to answer.

□ □ □ □ □

Think Global Health: So what's the bottom line? What's the outlook?

PERLMAN: Well, you know, that's a hard question to answer, because depending on how contagious it is you're going to get a different answer. If it turns out to be different than other coronaviruses and more contagious, then it's more likely that there's going to be a bigger outbreak. People don't have immunity to this virus, so unlike flu where all of us, most of us, have some level of immunity to the virus that's circulating, here there'd be no immunity in the population. But that seems unlikely based on what we know about coronaviruses.

It's more likely that once it's recognized this is a big deal, particularly in China, as they're doing already—they're quarantining a city, which may be a bit much—but they're making sure that sick patients are staying out of the general population. And that's really the best you can do. And you can make sure that people who fly, or take trains, or bus, or whatever else, aren't sick. And if there's enough cases you may say: Hey, we're not going to let anybody out in the very near future. But, again, that seems excessive to me.

These are the kinds of decisions that public health officials have to make that are not trivial—and sometimes they get it right, and sometimes they get it wrong. But you're just hoping that they're doing the best that they can, making the most rational decision based on the information they have. And there may be more information than we have. We know how many cases there are in the press, but we don't know what the real number is in China. And maybe the Chinese don't know either, particularly if there's people walking around who aren't clinically ill. You could have more cases than you even think you have.

EDITOR'S NOTE. This interview was conducted by phone. What is printed here was taken verbatim from the transcript but edited slightly for length and clarity.