At the end of April, President Joe Biden released the Declaration for the Future of the Internet, a statement of principles endorsed by the United States and sixty partners around the world. According to the White House, the declaration advances "a positive vision for the Internet and digital technologies." The document constitutes a response by the United States, its democratic allies, and likeminded countries to multiplying threats that have made the internet less free, open, global, interoperable, and secure.

The declaration connects its vision for the internet with policy priorities supported by the endorsing nations, including defending democracy, promoting the rule of law, expanding commerce, and protecting human rights. These priorities communicate why the internet matters to the signatory countries. In that sense, the declaration is an ideological statement about the "immense promise" of a technological capability that must be politically redeemed.

The declaration is an ideological statement about the "immense promise" of a technological capability that must be politically redeemed

The declaration does not list every policy priority supported by its vision for the internet. For example, it does not mention the effort against Russian aggression in Ukraine. It also does not reference global health, an interesting omission amid the most devastating pandemic in a century during which internet activities helped and harmed policy responses. Even so, the declaration is important for global health because it reflects an emerging perspective on international politics that will shape foreign policy approaches to global health for the foreseeable future.

The Internet Is in Trouble

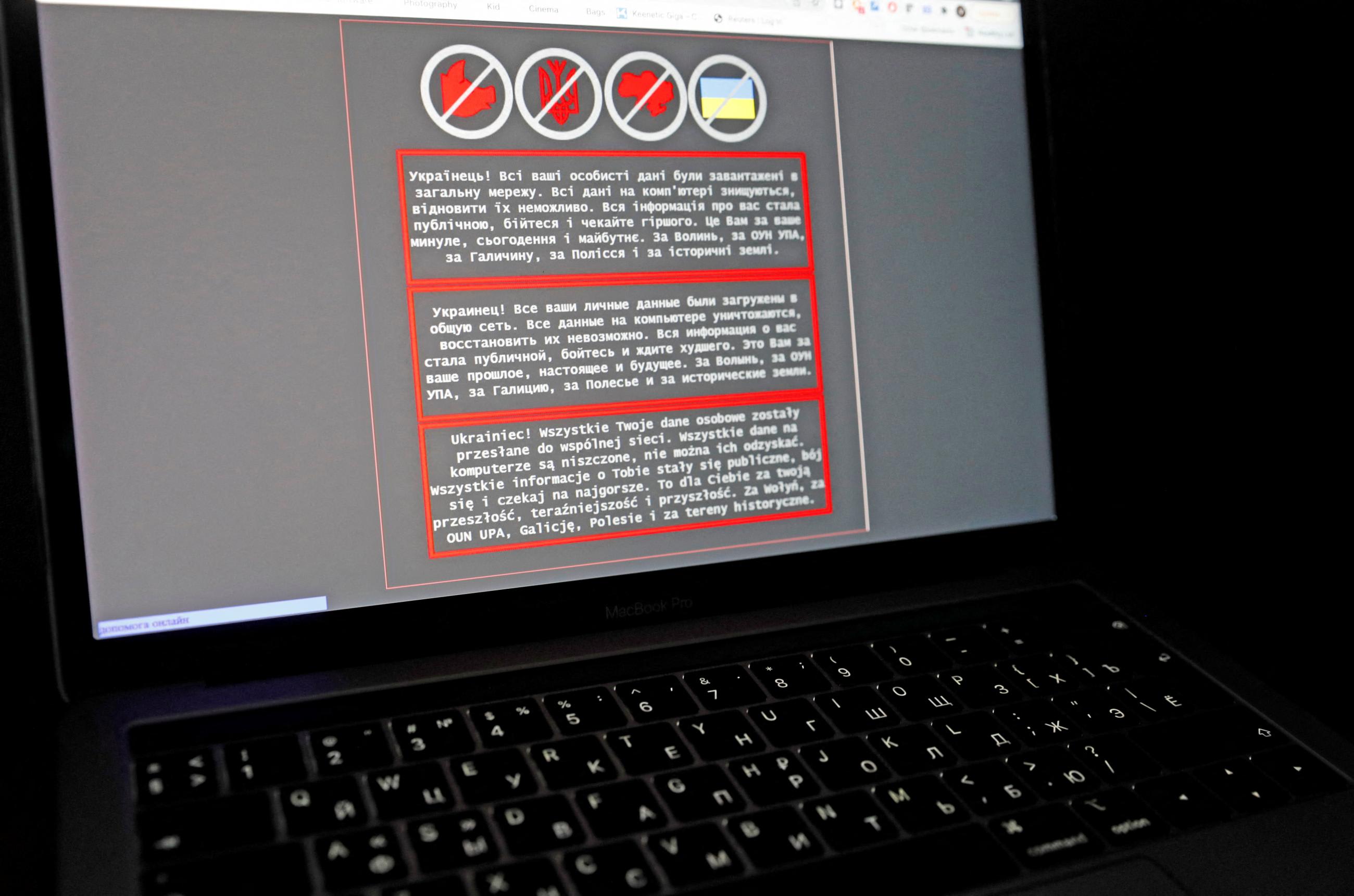

The declaration acknowledges that the "belief in the potential of digital technologies" to support democracy, peace, the rule of law, sustainable development, and the enjoyment of human rights and fundamental freedoms has been battered. It identifies challenges posed by digital repression, malicious state cyber operations, internet shutdowns, cybercrime, online incitement of radicalization and violence, cyber interference with democratic processes, and the proliferation of disinformation.

The litany of problems in the declaration aligns with longstanding concerns about the decline of internet freedom, the rise of digital authoritarianism, and the failure of efforts to prevent, protect against, and deter cybercrime and other malign online activities undertaken by governments and non-state actors.

The declaration's blueprint for "reclaiming the promise of the Internet" breaks no new ground because the ideas presented have been offered before as solutions to the internet's travails. The document's importance arises more from the attempt to build a concert of likeminded countries and partners committed to using agreed principles to achieve common objectives. In short, the declaration contains a geopolitical strategy to advance ideological preferences about the use of technologies that affect almost every human activity.

Global Health Is in Trouble

The COVID-19 pandemic is a global health tragedy, made more painful by decades of warnings about the dangers that pandemics pose and the woefully inadequate efforts to prepare for them. The global wreckage caused by the coronavirus proves that the optimism about the internet's ability to support and advance global health has been naïve.

As happened in other policy areas, global health endeavors—such as disease surveillance—have been integrated into internet-linked digital technologies. However, this strategy has not been transformative for global health. Even before COVID-19 emerged, the failure of countries to prepare for serious infectious disease outbreaks was well-known. The prevalence of noncommunicable diseases was still expanding when COVID-19 hit. Health threats created by climate change were increasing as international efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions failed and the need to address climate adaptation received insufficient attention and resources.

Global health provides a poor foundation for geopolitical strategy and ideological claims

To make matters worse, the pandemic exposed vulnerabilities in the health sector highlighted in the Declaration for the Future of the Internet. Health facilities experienced more cybercrime attacks. Countries conducted cyber espionage operations against vaccine research and development efforts. State and non-state actors spread disinformation online that adversely affected public health interventions, including social distancing, masking, and vaccination. Many governments used the pandemic to intensify digital repression and undermine human rights. The ability to digitize and rapidly share genetic sequence data exacerbated controversies about equitable access to the benefits that the use of such data produces.

A Declaration for the Future of Global Health?

Global health officials and bodies have responded to these problems by continuing to harness the internet for health purposes. These efforts include reducing the "digital divide" that prevents people in low-income countries from accessing health information and crafting policies to counter malicious cyber activities detrimental to health protection and promotion activities. However, to date, these efforts lack the geopolitical and ideological features that make the Declaration for the Future of the Internet significant.

For example, the Independent Panel for Pandemic Preparedness and Response proposed that the World Health Organization "establish a new global system for surveillance, based on full transparency by all parties, using state-of-the-art digital tools to connect information centers around the world and including animal and environmental health surveillance, with appropriate protections of people's rights." This proposal echoes the techno-optimism of the early internet era and fails to address the relentless rise of cyber sovereignty, cyber insecurity, digital authoritarianism, digital repression, and online disinformation that jeopardizes the transparency and trustworthiness of all information flows, not just those relevant for health.

The Declaration for the Future of the Internet draws geopolitical and ideological "lines in the sand" concerning the internet as a global technology. This approach raises the question of whether something similar should happen in global health, a field traditionally uncomfortable with power politics and ideological conflict. Proposals to strengthen global health diplomacy and governance after COVID-19 include recommendations to create coalitions of likeminded states committed to certain political principles. These proposals reflect pessimism that multilateralism offers a meaningful pathway in an increasingly divided world, and a skepticism that global health can escape the accelerating vortex of geopolitical and ideological competition.

Moving global health policy in the direction of geopolitical and ideological line drawing, as the declaration does for the internet, would provoke resistance within the global health community. But the real problem with envisioning a "Declaration for the Future of Global Health" along the lines of the internet declaration is that global health provides a poor foundation for geopolitical strategy and ideological claims.

The most powerful champion of the Declaration for the Future of the Internet—the United States—was the unrivaled leader in global health from the early post-Cold War years until COVID-19 emerged. In this period, China, Russia, and other authoritarian countries turned the geopolitical and ideological tables against the United States without attempting to compete with America on global health. This dynamic mirrors the Cold War when international health played no strategic role in balance-of-power and ideological competition between the United States and the Soviet Union. Further, the behavior and performance of democracies around the world during the pandemic also damaged the case that democracy is better for global health. Why the United States and its allies would believe that global health leadership after COVID-19 can produce serious geopolitical or ideological advantages is not clear. Likewise, the pandemic has been no geopolitical or ideological boon for China or Russia.

Put bluntly, global health is not geopolitically or ideologically important in international relations. As the Declaration for the Future of the Internet demonstrates, countries believe that some issues are significant enough to draw geopolitical and ideological lines in the sand. In such a world, how governments think and act about power and ideology threatens to marginalize global health in foreign policy. Perhaps that's why the declaration did not mention global health.