The global spread of COVID-19 has laid bare our vulnerability to health threats and triggered a fundamental rearrangement of everyday life. As of late September, 4.7 million people had died across nearly every country. While the pandemic's health implications are clear, more subtle—yet just as insidious—is its impact on democracy and freedom worldwide. The volume of repressive responses to COVID-19 in both dictatorships and democracies reflects a growing global trend toward authoritarianism, which features the politicization of natural crises. The pandemic serves as another reminder of the imperative to protect and strengthen freedom and democratic governance around the world.

"The pandemic has exacerbated the 15-year decline in global democracy"

COVID-19 and the Global Decline in Democracy

The pandemic has exacerbated the 15-year decline in global democracy that Freedom House has documented in Freedom in the World, its seminal evaluation of political rights and civil liberties. Of the 79 countries and territories that experienced a net decline in freedom in 2020, 35 of these declines—or nearly 45 percent—were related to the pandemic. This year's unequal and politicized vaccine distribution, along with the spread of new variants, threatens to prolong the health crisis while further damaging global democracy.

Limits on rights, such as freedom of movement and assembly, can be legitimate responses to a public health emergency—provided they are proportionate, limited in duration, and nondiscriminatory. However, states too often went beyond these criteria with COVID-19. Governments across the world enforced lockdown measures with violence, criminalized forms of free speech, and designed far-reaching states of emergency that sidestepped due process protections and increased executive powers.

Did COVID-19 Lay the Groundwork for Further Deterioration?

Beyond COVID-19's immediate impact is the pandemic's potential to deepen the existing democratic recession in years to come. Government responses to COVID-19 have parallels to the aftermath of the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, when governments in the United States and other countries instituted sweeping surveillance programs and restricted due process rights. Many of these programs remain with us in some form 20 years later. The protracted spread of COVID-19 similarly triggered a shift toward disproportionate government powers and a rash of adverse consequences for democratic norms that will be challenging to roll back.

Authoritarians turned pandemic responses into another hammer in their toolbox. In Cambodia, the one-party legislature passed new guidelines for states of emergency that authorize limiting or even banning movement and gatherings. The guidelines also empower the government to surveil digital communications and impose penalties for spreading information deemed to cause alarm or undermine national security. The government has yet to invoke the new emergency provisions, suggesting that authorities exploited the pandemic to create new powers for use during future crackdowns.

"Government responses to COVID-19 have parallels to the aftermath of the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001"

The military in Myanmar has attempted to delegitimize the civilian leaders deposed in February's coup by pointing to purported violations of COVID-19 restrictions. Both President U Win Myint and de facto civilian leader Aung San Suu Kyi stand accused of breaching pandemic-related limitations on interacting with crowds, in addition to other unrelated charges. A surge in coronavirus cases, driven by the Delta variant, led to their trials being suspended. They each face years in jail with their likely imprisonment effectively turning back the clock to a time before the military began sharing power with elected civilians.

The weaponization of COVID-19 responses is not limited to dictatorships. In Hungary, the increasingly authoritarian government of Viktor Orbán passed a series of emergency measures in the spring of 2020 that allowed it to rule by decree before coronavirus cases climbed to significant numbers in the fall. Misuse of these new powers included the redirection of tax revenues away from municipalities led by opposition parties. Orbán and his allies have since politicized vaccine distribution ahead of next year's parliamentary elections, falsely claiming in a political campaign that the opposition was anti-vaccination.

In El Salvador, the administration of President Nayib Bukele, who has dragged the country toward authoritarianism, cited the public health threat from COVID-19 to further restrict government transparency, including by closing two Court of Auditors offices that had supposedly been monitoring both the finance ministry and the office of the president. In May 2021, lawmakers from Bukele's party ousted five judges from the Supreme Court's Constitutional Chamber, which had ruled against the administration, including against its draconian responses to COVID-19.

The pandemic has hit marginalized populations hard, with structural inequality causing disproportionate spread and powerful actors seeking a scapegoat for the crisis. Governments and societies frequently blamed disadvantaged populations for spreading the virus. Such smears were levied against Muslims in India, refugees and asylum seekers in Malaysia, and Nicaraguan migrants in Costa Rica, among other examples. The scapegoating in India was a natural extension of the government's discrimination against the Muslim minority, which has severely damaged Indian democracy.

In It for the Long Haul

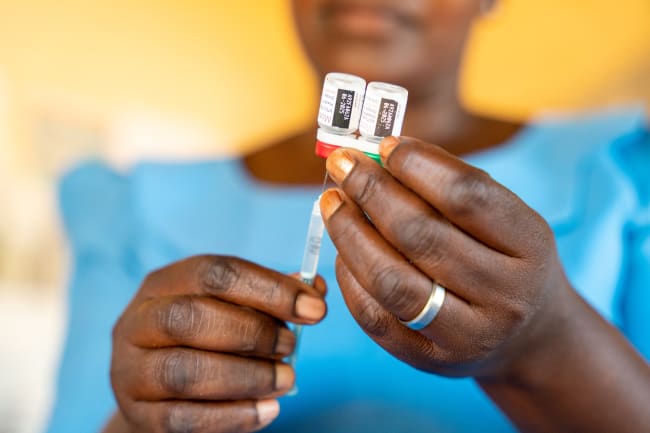

Even with the development of effective vaccines, many people around the world have not been vaccinated—only a shocking two percent of Africans have received vaccinations, for example. The lack of vaccine access has fueled the spread of dangerous mutations, further imperiling global health and democracy. In shaping emergency response plans and preparing for future crises, governments must implement expert consensus within an international human rights framework to minimize politicization. Emergency response plans should be legitimate, proportionate, time-restricted, and nondiscriminatory and should ensure that the entire population has access to factual information.

"The pandemic hit marginalized populations hard, with structural inequality causing disproportionate spread"

Authoritarian leaders are unlikely to adhere to these principles, so democratic governments and other stakeholders must identify and condemn human rights abuses and the undermining of accountability mechanisms both at home and in other countries. Perpetrators should also be held to account. These steps will complement other actions that should be taken to strengthen democracy and counter authoritarianism, including supporting civil society and grassroots movements, prioritizing the fight against kleptocracy and international corruption, and improving laws that guard against foreign influence over government officials.

The pandemic also presents an opportunity to bolster democracy more broadly. COVID-19 has shone a spotlight on the weaknesses of democracies, such as the politicization of natural phenomena and the disproportionate impact on certain population segments. Through emergency response and recovery efforts, governments now have the opportunity to address these types of weaknesses more holistically in democratic governance. By committing to broader democratic principles and human rights protections, we can begin to reverse the democratic decline and respond to COVID-19 and future crises better.