In late September 2025, China's ambassador to Nigeria announced a plan for Chinese companies to build an insulin-production facility in the West African nation. That announcement follows a string of deals between Nigerian and Chinese companies to construct facilities for manufacturing antimalarials and antiretrovirals. Although these agreements are made between corporations, they are part of China's Health Silk Road (HSR) strategy.

The HSR is one element of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Launched in 2013 by Chinese President Xi Jinping, the BRI is a strategic infrastructure-development project to enhance global connectivity and cooperation. The BRI is primarily focused on China's land- and maritime-infrastructure goals, whereas the HSR emerged as a distinct aspect of China's broader strategy for foreign engagement.

Although the HSR is associated most frequently with China's foreign aid, it also includes public-private partnerships that finance institutions through loans and investments. Chinese companies manage the implementation, such as with Shanghai Fosun Pharmaceutical's investments in Nigeria. Since the COVID-19 pandemic, these partnerships have become increasingly relevant to China's footprint in the global health space.

As China's economy and capacity grow, it is stepping up as a significant player in global health in ways that differ from the traditional U.S.-dominated frameworks of multilateral, donor-recipient, global-goods-oriented aid. China prefers a bilateral, sovereignty-focused model, based on concepts of equal partnership and brotherhood. Such partnerships range from population health improvement to digital health acceleration to out-of-patent medicines manufacturing, all areas where China can offer developing partners recent and relevant expertise. The United States and EU are now adopting these direct bilateral aid models, which form the basis for the America First Global Health Strategy and the EU's Global Gateway Strategy.

An opportunity exists for countries to engage with China and harness the speed and resources of the country's models for overseas development aid, as well as its booming private sector

The withdrawal of donor funding from the United States and European countries threatens to undo decades of work, such as efforts to eliminate diseases like HIV, TB, and malaria, but global health is not in crisis. An opportunity exists for countries to engage with China and harness the speed and resources of the country's models for overseas development aid, as well as its booming private sector. These prospects benefit from strong stage support, such as vaccine manufacturing and digital health innovation—all while preserving the accountability and responsibility of multilateral and government actors.

The Health Silk Road's Evolution

The HSR has evolved since China and the World Health Organization (WHO) signed a memorandum of understanding in 2017, which set a high-level commitment for greater cooperative working between the nation and the global health agency.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, China leveraged the BRI's infrastructure and networks to send diagnostics, respirators, and personal protective equipment to countries such as Italy, Turkey, Laos, and Malaysia. Estimates claim that $4 billion worth of donations were disbursed between 2020 and 2022 through the HSR, not including the vaccines and equipment sold to countries at affordable prices.

China's step-up to health leadership during the pandemic demonstrated the country's ability to rapidly leverage the expansive HSR when required. That experience also primed China to take on a greater role in the absence of U.S. funding and meet its goals of enhancing soft power that were set out in the original Three-Year Plan for Belt and Road Health Cooperation.

China's Global Health Footprint

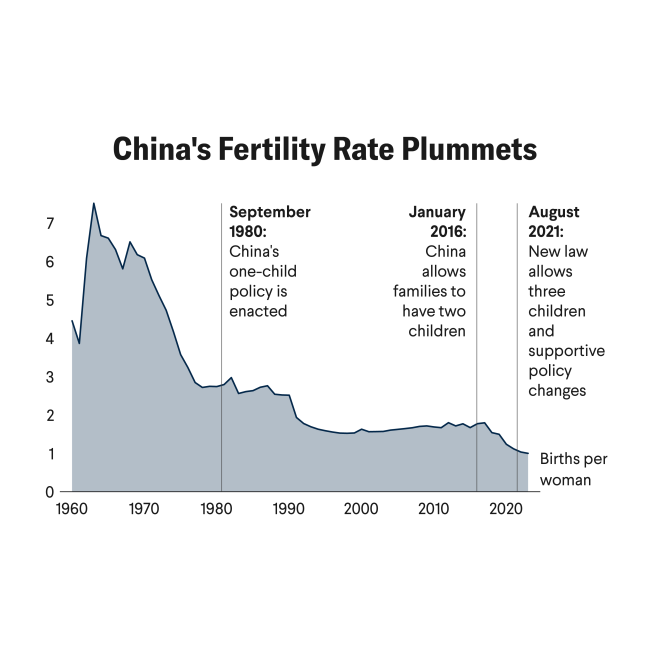

Health is a central priority for China, at local, national, and international levels. Long-term policy blueprints such as Healthy China 2030, and the thirteenth and fourteenth Five Year Plans, continue to reiterate ambitious goals for promoting universal health coverage, access to care and medicines, and strategies to address aging populations, rising chronic disease burdens, and risks of pandemic-potential disease.

In recent years, China has evolved from being a recipient of global aid to a provider—first with the Global Fund in 2013 [PDF] and then with GAVI in 2015. Since making this transition, China has been engaging in bilateral negotiations with low- and middle-income countries to strengthen health systems. This work is not new for China, as its South-South global health partnerships have existed since the 1960s, but the scale and direction have evolved significantly.

To illustrate, China's first overseas medical team was dispatched to Algeria in 1963 to provide technical support and establish diplomatic relations with the newly independent country. At the present day, China has grown into a major donor of bilateral global health aid, which led to enhanced relationships with more than 100 low- and middle-income countries.

One example of present global health cooperation is China's relationship with Tanzania. Based on its own experience of reducing malaria incidence from 30 million cases annually in the 1940s to less than 5,000 annually in 2013, China has supported developing similar strategies for countries such as Papua New Guinea and Tanzania. China's Center for Disease Control and Prevention reported that in Tanzania's intervention areas, malaria rates fell by as much as 80% between 2015 and 2018.

Through partnerships with Ifakara Health Institute in Tanzania, the UK Department for International Development, and the Gates Foundation, China provided technical support and offered best practices to local health-care workers. Chinese investments in African medicines manufacturing capacity were a key outcome during the 2024 Forum on China-Africa Cooperation, building on China's experience of rapidly scaling up their national pharmaceutical manufacturing industry. This not only shows how China is ready to step up as a global health leader but also how it is already showing leadership by utilizing its own experiences to support other countries with the achievement of global goals.

At the same time, China is increasingly visible on the multilateral stage, particularly in global health governance. Its $500 million pledge at the World Health Assembly in May 2025 raised the country's profile in health financing just as the United States pulled back on funding. These diverse paths enable China to present itself to developing partners and be viewed on the global stage as a responsible actor.

Still, China's role in global health is anticipated to significantly evolve over the upcoming years. At that World Health Assembly, multilateral forums delegations voiced their support for a strong global health governance and China's readiness to scale up its role. Already a global leader in digital health, electronic records, and AI diagnostics and therapeutics, China is likely to collaborate in these areas with partner countries under the HSR.

The recent years of the HSR have not replicated the traditional global-health support mechanisms, nor have they wholescale revised the global health architecture. As countries move into a new phase of global health cooperation, the HSR has the potential to be an effective tool among many within a strengthened global health system. The rest of the world should take heed as an opportunity to learn from the past and build a stronger global community.