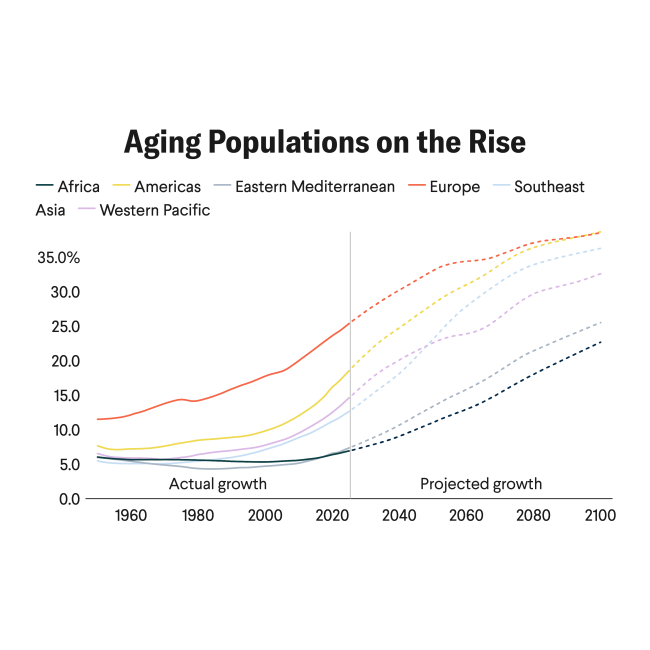

Brazil is facing a window of demographic fragility, a phase in which its social protection system, public health infrastructure, and economic resources are not yet ready to support a rapidly aging population. Today, about 11% of the population is 65 or older, a share that is expected to double by 2040, at which point the country will have more older adults than children.

That milestone will reshape Brazil's social and economic landscape and demand major adjustments to social policies and the health system. Unlike European nations, which had centuries to adapt their pension and health systems to an aging population, Brazil is navigating this shift without the economic strength or institutional capacity characteristic of high-income countries.

Fertility has plunged from six children per woman in the 1960s to fewer than two today, which is below the population replacement level. Meanwhile, life expectancy has risen from 66 years in 1990 to 76.4 in 2023. Brazil is getting older faster than wealthier countries did, compressing decades of demographic change into just a few generations and straining already fragile systems.

Brazil's rapidly aging population, regional inequalities, fragile primary health-care systems, and the growing burden of noncommunicable diseases (NCDs)—especially hypertension and diabetes—are exposing structural weaknesses in its Unified Health System (SUS). Although the SUS provides universal coverage, it struggles to consistently deliver preventive care to elderly populations in rural and underserved urban areas.

To ensure that Brazil can adapt to this demographic shift, it needs to invest in prevention, community innovation, and consolidation of primary care.

The Burden of Chronic Diseases

As Brazil's population ages, NCDs are surging. Hypertension, diabetes, and cancer account for more than 70% of deaths in Brazil [PDF], showing how profoundly the country's health profile has shifted. Many of the causes of disability among older Brazilians could be prevented or managed with low-cost interventions such as regular blood pressure screening, nutritional counseling, and community-based physical activity programs.

Hypertension, diabetes, and cancer account for more than 70% of deaths in Brazil

Too often, these conditions are diagnosed late, leading to higher treatment costs and avoidable suffering. Between 1990 and 2019, Brazil saw a decline [PDF] in mortality and disability-adjusted life years from NCDs, but from 2019 to 2021 that progress stalled, especially for hypertension and obesity.

By 2030, if current trends continue, the country could face 5.26 million new NCD cases and more than 808,000 deaths related to overweight or obesity. Those excess cases and deaths will further strain Brazil's underresourced primary care system.

The Unified Health System

Brazil's Unified Health System and the Family Health Strategy (Estratégia Saúde da Família, or ESF) are often cited as a model for expanding primary care in middle-income countries. By using community health workers to deliver care to underserved areas, the ESF reaches about 65% of Brazil's population, but coverage remains uneven, especially in poorer regions.

There, chronic underfunding, shortages of health professionals, and deep regional inequalities make preventive care for older adults inconsistent and often inadequate. As a result, many seek medical care only at advanced stages of disease, when longer hospitalizations, soaring costs, and a loss of independence could have been avoided with earlier interventions. In the absence of significant reform, the number of older adults seeking late-stage care is projected to increase by 2040.

The Role of Intersectoral Policies

Confronting the challenges of aging requires more than hospitals and medications. It calls for intersectoral policies that ensure accessible public transportation, adequate housing, caregiver support, and opportunities for active aging. Local initiatives from the nonprofit Social Service of Commerce—which combine physical activity, healthy eating, and social engagement—have already shown positive results in preventing falls, controlling blood pressure, and improving mental health among older adults.

Yet isolated local projects are not enough. Brazil needs national strategies that make healthy aging the norm, not the exception. Other countries facing similar transitions provide examples. Japan's community-based integrated care system provides long-term care insurance, home-based health services, and neighborhood support centers that help older adults remain both independent and socially connected. Chile and Costa Rica have also strengthened primary care networks [PDF] that offer continuous, preventive care for older populations. These models show that aging can be met with resilience rather than crisis.

Recent measures in Brazil include the expansion of the Family Health Strategy, the relaunch of the National Primary Health Care Policy, investments in digital health and telehealth programs, and updates to the National Policy for Older People's Health. The federal government has also included health and aging initiatives in the new Growth Acceleration Program (Novo PAC), aiming to modernize hospitals and expand access to specialized geriatric care. Those reforms, though still uneven in implementation, show that Brazil is beginning to address the demographic challenge.

The Future at Stake

Although many view aging populations as an inevitable crisis, Brazil has an opportunity to transform its health systems by creating inclusive and sustainable policies.

Rather than reacting only when problems arise, a choice that incurs higher costs and excess suffering, Brazil can invest now in prevention, community innovation, and the consolidation of primary care, preparing a society in which longevity means autonomy and well-being.

If Brazil uses this moment to reduce inequalities and expand the reach of its health policies, it will have the opportunity to turn aging into a driver of social resilience and human development.