The COVID-19 pandemic and its secondary impacts have engulfed the globe in a historic crisis — but they also present an opportunity to help the world build back better, and more equitably. The U.S. Congress is on course to provide $4.65 billion for global health as a part of President Biden's $1.9 trillion coronavirus relief package. This presents a critical opportunity to direct urgently needed U.S. assistance to where it is needed most by tapping the skills of community health workers (CHWs). Unless the United States recognizes the essential role played by CHWs, and provides the necessary funding to support them, we will not be able to improve equitable access to essential health services and interrupt the global spread of the virus.

CHWs are trusted members of the community who are trained to provide health services in their neighborhoods

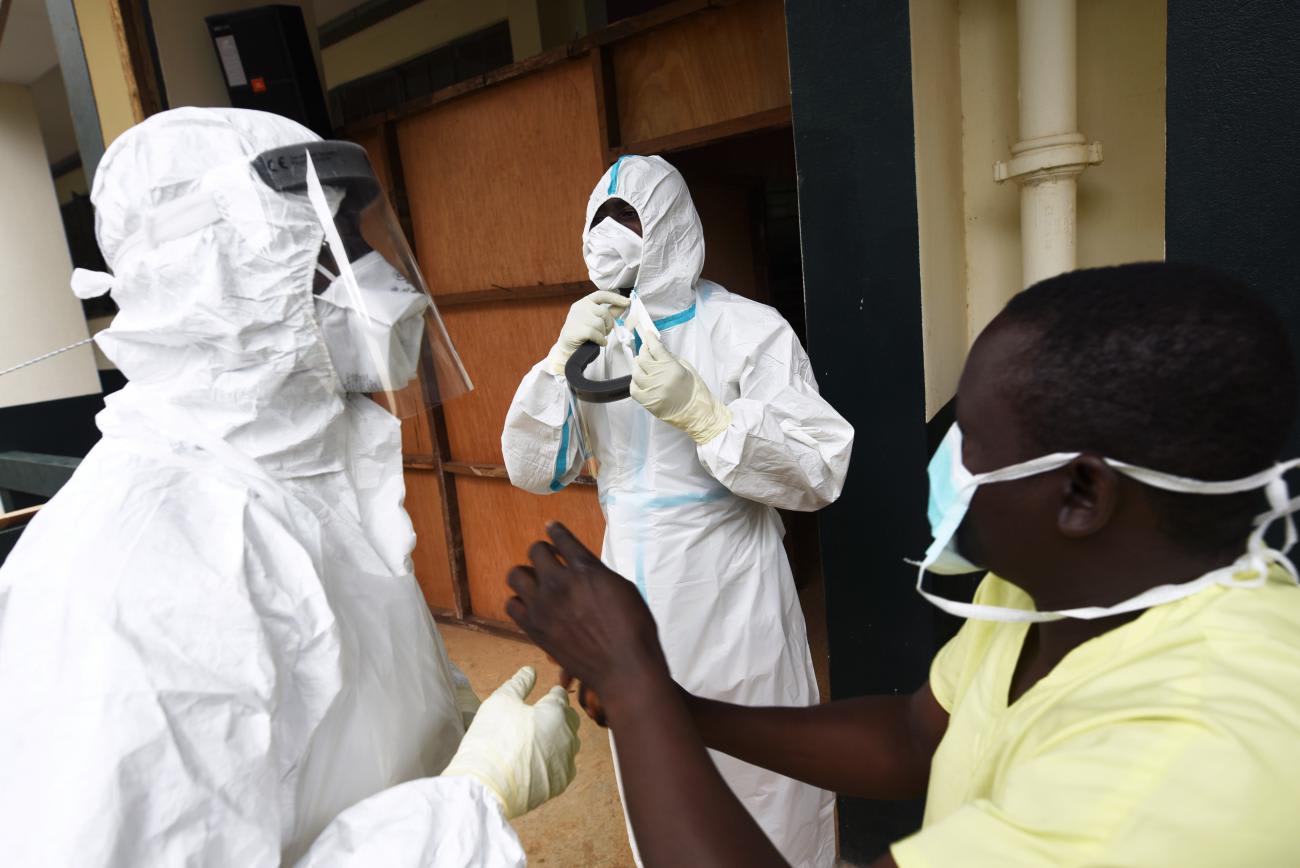

CHWs are trusted members of the community who are trained to provide health services in their neighborhoods. Acting as a link between the health system and individuals, they provide reliable information, carry out health promotion and prevention activities, implement vaccination campaigns, and treat illness. CHWs, most of whom are women, have played a vital role in many global health efforts. They were among the frontline health workers at the forefront of U.S. investments in HIV, which helped save an estimated 100 million children's lives from 1990 to 2015 and cut AIDS-related deaths by 60 percent since 2004. Ever since the first cases of COVID-19 were diagnosed, CHWs have played an important role in maintaining essential health services and fighting the pandemic. As the world's largest-ever vaccination campaign gets underway, they can play an even bigger role: from identifying and enrolling target populations, to tracking and reporting outcomes.

This is important because to vaccinate the global population, we can't just rely on the existing health-care workforce. Even before COVID-19, the world was already projected to be short 15 million health-care workers by 2030. The global vaccine roll-out over the next 24-36 months will add millions more to that deficit. CHWs, who are quick to train and deploy, can help fill this gap – if they are well supported.

The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and the World Health Organization (WHO) recommend that CHWs be paid, trained, supervised, and equipped as an essential cadre of the health workforce — but U.S. funded programs routinely ignore this guidance. Incredibly, 86 percent of CHWs in Africa are unsalaried and receive little or no compensation. In far too many programs, CHWs rarely receive ongoing training necessary for accreditation; they are routinely handed new responsibilities with little supervision or oversight; and they are last in line for life-saving supplies, including personal protective equipment and COVID-19 vaccines. This fundamental injustice imperils our long-term success in global health. Without good design, CHW programs are less resilient during crises, allowing pandemics to take hold and often leading to declines in utilization of essential health services that can ultimately kill more people than a pandemic itself.

Given the scale and schedule of the vaccine roll-out, the urgency of investments in the health workforce cannot be overstated

This needn't be the case. By tapping the emergency resources from Congress, USAID has an opportunity to help programs achieve a higher standard for CHW programs and strengthen the global health workforce. USAID should employ its own evidence-based resources for CHW programs, such as the Community Health Worker Assessment and Improvement Matrix, to ensure that this emergency support goes to CHWs who are fairly paid, well-trained, adequately supervised, and fully equipped to improve the health of their communities during this moment of profound crisis.

Beyond the emergency package, President Biden should likewise include targeted investments in health systems, including in support of CHWs, in his forthcoming FY2022 budget. Given the scale and schedule of the vaccine roll-out, the urgency of investments in the health workforce cannot be overstated. Current health workforce capacity is wholly inadequate to the task of both putting health programs back on track and responding to the pandemic. This funding will need to be sustained over multiple years if the world is to have a chance of ending COVID-19 and avoiding further disease and economic fallout.

Investments aimed at strengthening the health workforce, including CHWs, will help countries be more resilient in the face of future health crises. Such investments are also key enablers of U.S. investments in programs that target specific diseases like HIV and malaria, which rely on a well-supported, well-equipped health workforce to achieve intended objectives.

It has never been more apparent that our individual health is only as strong as our neighbor's health-care system, and that a strong health system is founded on a well-supported health workforce. The Biden Administration and the U.S. Congress should recognize the critical role of CHWs in the current pandemic response and in the long-term. Let's ensure CHWs are well-supported, not only because there is an ethical imperative to do so, but also because good program design will help build resilient, equitable health systems that can withstand future threats.