In early 2020, reports of tuberculosis cases fell by 60 percent in India. The massive decline of one of the world's most deadly infectious diseases might have been an unanticipated positive consequence of the pandemic. However, the decline occurred as stay-at-home orders were instituted, people steered clear of health facilities to avoid exposure to COVID-19, and health-care workers and supplies were stretched to their limit.

Amidst these events, were tuberculosis cases truly declining? Or were health-care workers simply missing more cases of tuberculosis? The answer is not straightforward. Nearly three years after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, scientists are still struggling to understand how the pandemic affected people's ability to access high quality and affordable health care.

Universal Health Coverage (UHC) Day, celebrated December 12, 2022, seeks to raise awareness of the global goal of achieving UHC—equitable access to effective health services without financial hardship for all people. The pandemic and its responses affected UHC across all its dimensions—health-care need, use, quality, and costs—in sometimes unpredictable ways. The pandemic also disrupted the measurement systems that researchers use to track countries' progress toward UHC.

Global Trend in Case Notifications of People Newly Diagnosed With TB

2015-2021

Mixed Signals

The case of tuberculosis illustrates why making sense of non-COVID health data collected during the pandemic is challenging. First, there is reason to believe that the rate of new tuberculosis infections decreased in the early stages of the pandemic. Masking and social distancing measures aimed at reducing COVID-19 infections could have also decreased community transmission of tuberculosis, since it spreads among people in close proximity. However, the decline could indicate that new cases went undetected as fewer people were screened for tuberculosis, and diagnoses of the disease dropped.

The pandemic likely affected the quality of care among people diagnosed with tuberculosis, potentially increasing their chances of dying from it. Effective tuberculosis treatment is labor intensive: a common strategy requires a health worker to observe patient treatment every day for months. In Kenya, 50 percent of tuberculosis patients couldn't access this care because of COVID-related disruptions to public transportation. While technology enabled some remote treatment, many health-care workers had to shift their focus away from treating other conditions to treating COVID-19 patients. Some researchers predicted that patients with tuberculosis would be 28 percent less likely to complete their first line treatment regimen due to these challenges. As is the case with cancers or other chronic diseases, missing early tuberculosis treatment can result in worse health outcomes in the future. Inconsistent treatment of tuberculosis also increases the likelihood of developing drug-resistant strains of the disease, which is also a challenge with other bacterial infections.

The data systems in place to measure tuberculosis infections and care were not able to capture all of these dynamics during the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, global reporting of tuberculosis cases depends on local screening programs to detect cases, which were likely disrupted—at least partially—in 2020. No data shows how much actual transmission decreased, though estimates suggest it was not enough to account for the reductions in reported cases. Similarly, assessing the quality of care is challenging because patients who were able to get treatment may have been better off than those whose diagnoses were missed.

The sum of these signals suggests that the COVID-19 pandemic likely did substantially harm the detection, treatment of, and quality of care, for tuberculosis, which will result in poorer health outcomes in years to come. However, incomplete data and the countervailing directions of the pandemic's impact limit our knowledge about exactly what happened and who was affected.

Affordability of Health Care

The effects of the pandemic on the affordability of health care, another key part of UHC, is similarly puzzling. If fewer patients were treated for tuberculosis in 2020, fewer patients would face immediate health-care costs. However, if patients develop more severe disease because they missed the chance to receive early treatment, costs and financial hardship could be more severe in the future.

An additional consideration is that many people lost work in 2020: in Kenya, 1.7 million people lost their jobs in the first four months of 2020 and in India, an estimated 74 million people fell below the poverty line. These changes in income could have affected whether health-care costs prevented tuberculosis patients from obtaining treatment. Even steady levels of health-care costs in 2020 might translate into higher rates of financial hardship, because payments would be drawn from a smaller income.

A Global Vision for UHC

The complexities with tuberculosis are emblematic of the challenges involved in assessing the pandemic's impact on UHC, which encompasses care for all diseases and health conditions, not just tuberculosis. Only the most basic data are available. For instance, many studies document reductions in essential health services in early 2020 including for HIV, tuberculosis, and cancer prevention and diagnosis. Contraception services and treatment for HIV, in contrast, were less disrupted in most countries because of increased health system efforts, though there is large variation between countries. But service disruptions don't tell the full story for UHC; the pandemic also altered health-care needs, the quality of health care, and the money available for care.

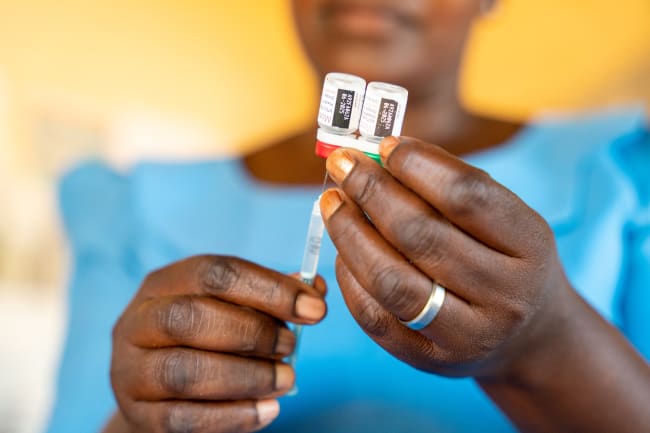

While the COVID-19 pandemic is no longer disrupting essential health service provision in most countries, the reverberations of the pandemic for UHC are likely to persist for years. The missed opportunities in 2020 to prevent and diagnose some diseases will translate into new and advanced health conditions for many people. Missed vaccinations for diseases such as measles could lead to future outbreaks. These conditions will increase the need for high quality health care including more screening, prevention, and treatment. Simultaneously, the pandemic sparked the acceleration of telemedicine and home-based care, which could transform care delivery in the future.

The pandemic's harmful effects on the global economy may also have consequences for governments' ability to pay for health care in the years ahead. In Kenya, "funds had to be diverted both at national and sub-national level [from UHC] to tackle the pandemic," says Elizabeth Wangia, a physician and monitoring and evaluation specialist with the UHC Secretariat in the Ministry of Health in Kenya.

Fears of a global recession persist, and with fewer financial resources, countries may decide to reduce their domestic health spending or cut their contributions to development assistance for health in low- and middle-income countries. All of these spending cuts may make more people vulnerable to the financial risks of health-care costs.

If better data existed to understand how the COVID-19 pandemic affected UHC, we could act now to prevent the worst possible outcomes from coming to pass. Data could help guide interventions to make them more targeted and effective for the families that need them most. Moving forward, more robust information systems are needed to capture disease incidence, quality of services, costs, and ultimate health outcomes to ensure countries sustain their pathways to UHC as we emerge from the worst of the COVID-19 pandemic.

EDITOR'S NOTE: The authors are employed by the University of Washington's Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). IHME collaborates with the Council on Foreign Relations on Think Global Health. All statements and views expressed in this article are solely those of the individual authors and are not necessarily shared by their institution.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS: The authors would like to thank Rebecca Sirull for fact-checking assistance and Professor Rafael Lozano and Katherine Leach-Kemon for providing feedback.