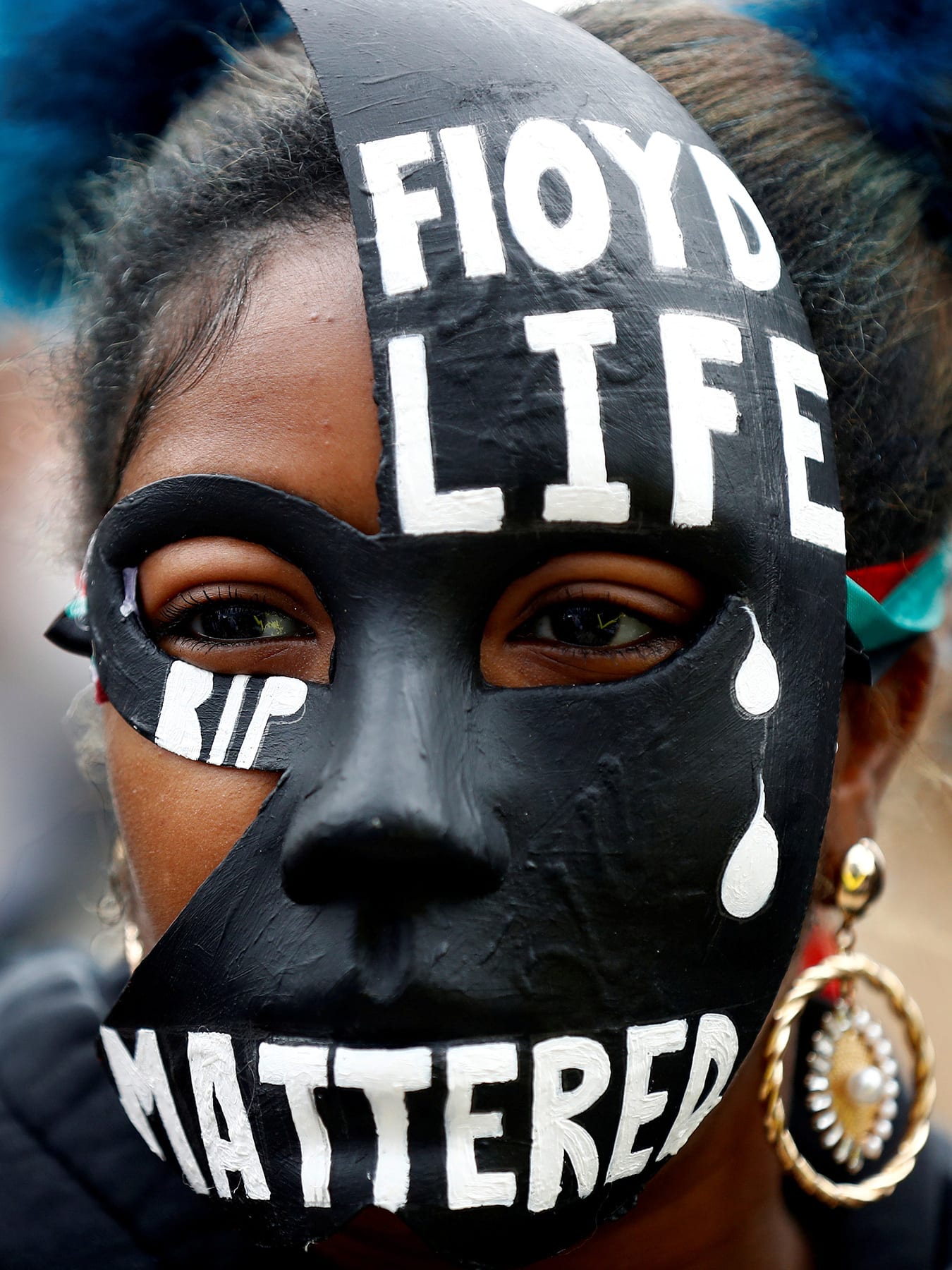

Across more than 400 cities in the United States, tens of thousands of Americans are pouring into the streets to protest racial injustice triggered by the killing of black people, including George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Tony McDade, and countless others whose names are not as familiar as the racism they faced in American society. Drawing massive crowds in major cities and large gatherings in many others, the protests are showing no signs of stopping, and there is concern among epidemiologists about a coming rise in the number of new coronavirus cases. The COVID-19 pandemic presents an opportunity to start tackling the persistent health and economic inequities that exist in the United States. Our national response to controlling the coronavirus must focus on Black and Latinx communities—our country's health and livelihood depend on it.

The COVID-19 pandemic presents an opportunity to start tackling the persistent health and economic inequities that exist in the United States

COVID-19 has proven to be much more deadly among Black and Latinx populations. Two weeks since the New York Times' powerful publication of nearly 100,000 mini obituaries of Americans who died from COVID-19, 10,000 more deaths were reported. A large proportion of them are Black and Latinx. In Washington DC, 75 percent of those who died of coronavirus were African Americans living in the most poor, most Black southeast neighborhoods of the nation's capital. The death rate for Black people in New York City is 92.3 deaths per 100,000 people and 74.3 per 100,000 for Latinx—compared to 45.2 per 100,000 for whites. In large urban cities around the United States like Chicago and Los Angeles, the virus is killing poor Black and brown communities at disproportionately high rates.

Poor Black and brown people have higher rates of underlying medical conditions, including heart disease, stroke, cancer, asthma, influenza and pneumonia, diabetes, and HIV/AIDS, which variously put them at much higher risks of coronavirus infection and death.

At much higher risks of coronavirus infection and death

The social and economic disparities of Black and Latinx communities—including the lack of adequate housing, education, health care, employment, and social supports—exacerbate these health conditions and in a sense, make those living in these communities more vulnerable to COVID-19. These disparities are the direct consequence of the enduring systems of social and economic racism that deny minorities equal health and economic rights, resulting in their shouldering a disproportionate burden in the COVID-19 pandemic.

As the country is confronting racial injustices and inequalities, we have a fleeting opportunity to begin to take small steps toward addressing the persistent inequity that Black and Latinx communities face in their daily lives, especially those living in poverty. An equity lens to our national response can effectively control the spread of coronavirus, and we must do so quickly with two important considerations.

Testing of COVID-19 should be concentrated among poor Black and Latino communities

First, testing of COVID-19 should be concentrated among poor Black and Latinx communities. With the volume of testing in the United States having finally improved, the focus should be on poor Black and Latinx neighborhoods, given the substantially higher death rate for those populations. Individuals living in these communities are more likely to be frontline workers (e.g., grocers, environmental service employees, health care workers, etc.) who cannot afford to work from home. The more testing and tracing that can be done in these communities, the faster local health officials can isolate and treat these vulnerable populations and prevent further spread within these neighborhoods and beyond. Crowded neighborhoods and lower quality housing with intergenerational families among these communities do not allow for effective quarantine or social distancing measures. Therefore, prevention resources, such as masks and sanitizers, should be provided free of charge.

Second, when a COVID-19 vaccine becomes available, it is likely that the initial supply will fall short of meeting demand. Historically, vaccine distribution prioritized high-income populations.

Equitable distribution of vaccine that acknowledges the disproportionate impact of COVID-19

Given the significantly higher death rates among poor Black and brown communities, we must prioritize these populations along with health workers and other essential personnel in the distribution and delivery of an effective vaccine. Since vaccines are designed to protect people who are at high risk for coronavirus and reduce transmission to those who are not vaccinated—creating herd immunity to protect a larger population—an equitable distribution that acknowledges the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on Black and Latinx populations is critical to achieving herd immunity.

These strategies will need to uphold health and human rights principles that respect individual dignity, build community trust, and examine systemic issues. In this resource-constrained COVID-19 era, a pro-poor and pro-Black approach to controlling the spread of coronavirus can be a small step toward dismantling the racial disparities and inequities that the pandemic has served to illuminate and magnify.