Four months after the first coronavirus vaccination campaigns began, many people—especially those living in low- and middle-income countries—are still wondering when their turn to get a shot will come and which vaccine they will receive. Based on government websites and statements, publications or contracts by vaccine manufacturers, and major local or international news media, Think Global Health has assembled that information. A table with detailed information and links to those sources, as of March 4, 2021, is included below and will be regularly updated.

The vaccine that countries are able to procure and administer is a form of influence for the sponsor of that vaccine and the nations that funded the vaccine's development. Starting with smallpox in the early nineteenth century, governments have used vaccine donation and vaccination campaigns to generate goodwill in other nations, increase the productivity of their colonies, ensure the safety of overseas nationals, and extend humanitarian benefits. During the Cold War, scientific cooperation over vaccines united even the most adversarial states, ushering in a "golden age" of vaccine science diplomacy. Since, vaccines have been branded as a tool to achieve global equity, and global health diplomacy has focused on ensuring universal or equitable access to these tools for low- and middle-income countries, such as with the universal polio eradication campaign. In the COVID-19 pandemic, however, the wealthiest nations have not uplifted poorer ones, and vaccine diplomacy has become a means of cementing spheres of influence rather than advancing global health equity.

Starting with smallpox, governments have used vaccine donation and vaccination campaigns to generate goodwill in other nations

It has been well reported that many wealthy countries have pursed a "me-first" approach to acquisition and distribution of proven safe and effective vaccines in the COVID-19 pandemic and the data illustrate the inequitable access that has resulted. Ninety-four percent of high-income countries have already begun vaccinations, but only four out of twenty-nine low-income countries –Afghanistan, Guinea, Syria, and Rwanda —have administered vaccines, and how Syria and Rwanda have procured their doses is unclear. Seventy-seven percent of nations that are administering vaccines are classified as high-income or upper-middle-income nations, according to the World Bank. Experts worry that this approach—known as vaccine nationalism—will leave many middle- and low-income countries without widespread access to vaccines until 2022 or even 2023, prolonging the pandemic and potentially causing as much as $9.2 trillion in global economic damages.

Without access to proven vaccines and unwilling to wait for wealthy nations to donate them, middle-income countries are turning to "unproven" vaccines—vaccines that had not completed or published the data from phase III trials at the time they were authorized and administered. Argentina, for instance, began administering the Gamaleya vaccine on December 29, 2020—a full month before Sputnik V's safety and efficacy data were published this week in The Lancet. Additionally, China has yet to publish the trial data for any of its vaccines—CanSino, Sinopharm, and Sinovac—that are currently being administered globally. When this data was collected, 24 percent of all middle-income countries currently administering vaccines were using Sputnik V, while 33 percent were using at least one of Chinese vaccines. No low-income or lower-middle-income country was using the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine, but 84 percent of high-income countries administering vaccines were.

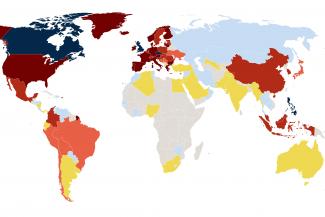

Looking at a global map of where and which vaccines are currently being administered, it is clear that spheres of vaccine influence fall as much along diplomatic lines as on economic ones.

In Europe, EU promises of assistance to Balkan states and access to EU vaccines have fallen flat, forcing Eastern European countries to wait or to turn to Chinese or Russian options; many have opted for the latter, often acquired through donations from Serbia. Some of the EU countries that are experiencing resurgences in coronavirus cases, such as the Czech Republic, Hungary, and Slovakia, similarly have begun exploring non-EU options as the bloc's rollout of vaccines has faltered.

In Latin America, the region is divided between Western (namely Pfizer/BioNTech), Russian, and Chinese vaccines, many of which have been donated by China, India, Israel, or Russia. Except for Colombia, each of the thirty-six Caribbean and Latin American countries receiving vaccines through COVAX are still waiting for those doses' arrival. Notably, of the nine Caribbean island nations that have launched vaccination campaigns, all but one are dependent on Indian donations or COVAX.

In Asia and the Pacific, donations from India and China have driven the start of vaccination efforts. Chinese donations thus far have largely gone to countries participating in its Belt and Road Initiative, while India has targeted its closest regional allies or small countries without other options, such as in the Pacific or Caribbean. Relative COVID-19 success stories such as Australia, Japan, New Zealand, South Korea, and Taiwan, only recently received vaccines, while most Central Asian states are currently completely dependent on COVAX or neighboring states for access.

In Africa, tragically, only fourteen countries have begun administering vaccines. More than half of those nations are using Chinese or Indian vaccines. Additional African nations are likely to launch vaccination campaigns in the coming weeks as more COVAX-provided doses arrive on the continent. Three countries, Angola, Ghana, and Ivory Coast, have already begun vaccination using COVAX-provided doses.

Across the globe, most donations from China, India, Israel, Russia, Serbia, and the UAE have been small. China and India are pledging, on average, fewer than 300,000 doses, the UAE has so far pledged no more than 100,000 doses to any one country, Israel and Serbia are offering donations of 10,000 doses or less, and Russia is providing donations ranging from 60 to 500,000 doses. To date, all pledged vaccines require a two-dose regime. While these donations have been enough to start vaccination campaigns in some countries, the quantities involved are not sufficient to satisfy local or global demand.

Perhaps the clearest message from this map of global vaccine access, now and projected by the end of 2021, is that global equitable access to vaccines hinges on the success of COVAX. COVAX is set to provide vaccine access to 46 countries that have not yet secured vaccines through bilateral or regional schemes or through confirmed donations.

Another important takeaway is that the vaccine from Oxford and AstraZeneca, which has been self-branded as a "vaccine for the world," seems to be living up its promise. Over half of lower middle-income countries that have begun administering vaccines are using the AstraZeneca vaccine. Between COVAX, regional procurement arrangements, and bilateral agreements, a total of 180 countries are expected to have access to AstraZeneca by the end of 2021.

Several factors contribute to the global popularity of the AstraZeneca vaccine—from its lower price point to easier storage—but the Serum Institute of India's licensing agreement to produce and distribute the vaccine is arguably one of the most important. The majority of low- and middle-income countries with access to AstraZeneca are set to receive doses produced by the Serum Institute of India, not by European manufacturers. This voluntary licensing agreement is particularly important as the EU looks to block AstraZeneca exports from Europe. However, AstraZeneca's global rollout, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa, may be slowed by recent evidence suggesting it less effective against the South African variant of SARS-CoV-2; South Africa already cancelled its AstraZeneca campaign, and Eswatini said it will not use the vaccine.

A total of 180 countries are expected to have access to AstraZeneca by the end of 2021

Most of Africa and much of southern Asia currently lack access to the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine—the other vaccine that COVAX intends to distribute in the first half of 2021. Sanofi, a French manufacturer, has agreed to help produce Pfizer/BioNTech's vaccine, but whether that will expand access to low- and middle-income countries is unclear.

Relatively few countries have finalized agreements to purchase Russian and Chinese vaccines, with a few exceptions in Latin America, the greater Middle East, and Asia. As more clinical trial data is published on the Russian or Chinese vaccines and they are independently verified, more nations may turn to these non-Western options. However, concerns over Sinopharm's and Sinovac's efficacy may push countries towards the Gamaleya Institute’s Sputnik V, particularly if EU vaccine export restrictions remain in force.

This tracker will be updated regularly. See the table below for detailed information about a country's specific vaccine deals and vaccination campaigns.

EDITOR'S NOTE: The authors would like to thank the following CFR research associates for their help and expertise in identifying vaccine donations: Erik Fliegauf, Joseph Haberman, Nolan Quinn, and Basia Rosenbaum.

This tracker was first published on February 5, 2021.