The Cassandra curse comes from a Greek myth that outlines the plight of a Trojan priestess who had the gift of prophetic vision but was cursed to have no one believe her predictions.

A new book, The Formula for Better Health: How to Save Millions of Lives—Including Your Own, leans on this myth to convey the dilemma for public health workers as they try to protect human life.

Authored by Tom Frieden, president and CEO of Resolve to Save Lives and former director of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the narrative outlines a formula to break this curse and guide health workers through a time of wavering public trust in scientists and their recommendations—intensified by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The formula comes with three ingredients: see the invisible, believe seemingly impossible solutions are possible, and create a world where people have healthier and longer lives.

As an example of the first, Frieden recounts the story of the 1991 multidrug resistant tuberculosis (TB) outbreak in New York City. An infectious disease specialist, Karen Brudney recognized a rise of drug-resistant TB early on and pushed people to see a pattern that hadn't become obvious—pushed them to see the invisible. After much disbelief and difficult coordination, lab testing was able to confirm the outbreak.

This formula—to see, believe, and create—not only applies to past outbreaks and public health successes but also can be brought into the fore. Think Global Health spoke with Frieden about how this formula could help foster optimism in the face of rising hostilities in public health and the dangerous discreditation of science and medicine.

This interview was lightly edited for brevity.

□ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □

Think Global Health: Much of your book carries lessons for the current moment and the great dissonance between the U.S. health and science community and the federal government. What are your general thoughts on what's happening?

Frieden: We're in a difficult time for public health. In some ways, nothing like this has ever happened. But at the same time, the principles of public health have not changed. By following those principles, we can chart a path to significant progress to save a lot of lives and reduce health-care costs.

Think Global Health: The formula to effectively manage public health crises requires us to see the problem, believe that it exists and can be fixed, and take action to create viable and sustainable solutions. Why is effective communication a major undercurrent for the success of this formula?

Tom Frieden: Communication is essential to getting the job done. It involves listening to the concerns of different communities, adjusting recommendations based on what people understand and are willing to do.

A good example is the 2014–16 Ebola epidemic in West Africa, where the outbreak couldn't be stopped until community leaders understood what was needed and were able to convey that to community members in ways that resonated. We had to change burial practices, which were deeply ingrained and had been important to people for hundreds of years, but were one of the major ways that Ebola was being amplified in those communities. Until community leaders understood this priority and conveyed what needed to happen, it wasn't possible to stop the outbreak.

We've reduced vaccine preventable illness so much that most people, even most doctors, have never seen many of the diseases

Communication is an integral part of every effective program and not just communications for the general public, it's also for policymakers, the media, and medical professionals. This is all essential to progress.

Think Global Health: Vaccines' efficacy and safety have come under fire. How can the formula be applied in an era that grows more divided and reinforces dangerous echo chambers of information?

Frieden: Anti-vaccination movements have existed since the first vaccines were identified. [In 1736,] Benjamin Franklin's child died from smallpox but rumors circulated that the boy had died from the vaccine. Franklin then took out ads in his own newspaper to curtail the spread of misinformation and make clear that his child had died not from the vaccination, but from the disease itself. He urged parents to get their children vaccinated.

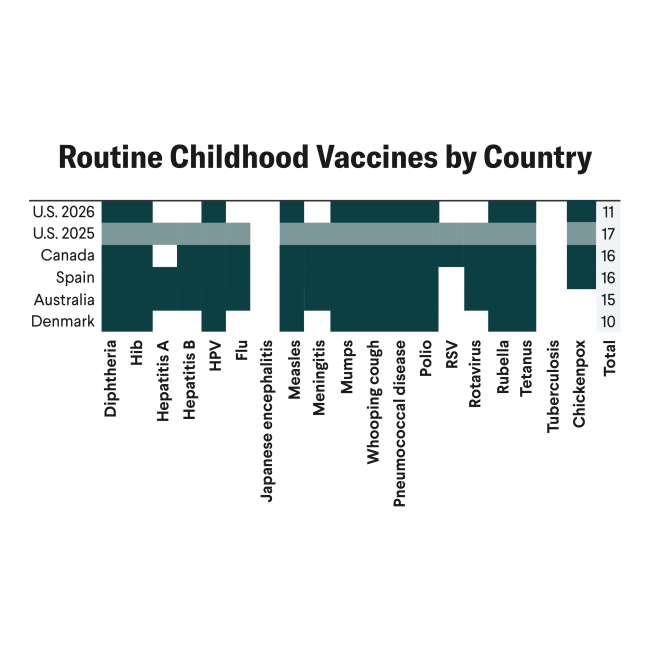

So, there's nothing new under the sun, but things are moving a lot faster. Other factors make vaccine communication particularly challenging. One is that vaccines are a victim of their own success. We've reduced vaccine preventable illness so much that most people, even most doctors, have never seen many of the diseases that were vaccinated against. My organization, Resolve to Save Lives, works in countries throughout Africa where some of these diseases, including measles, remain common and quite deadly. There we see much less reluctance to get vaccinated because people see what happens if they don't.

One of the book's themes is breaking the Cassandra curse. For many years, public health has been able to predict the kind of illnesses and deaths that will affect people but been unable to prevent them. Now we have the tools and technologies to prevent many of those diseases. So, on one hand, we have more vaccines, but on the other, fewer obvious vaccine preventable diseases, and thus there's a real gap in perception.

One gap that needs further work is the issue of conflicts of interest.

Vaccine manufacturers have a really important role: to make effective vaccines and conduct the studies to prove that they've done so. Their role is not to recommend who gets vaccines, however. Only people who have no conflict of interest with vaccine uptake should be making recommendations—to prevent undermining confidence in vaccination. To build public trust, avoiding both impropriety and the appearance of impropriety in things like vaccine recommendations is essential.

Think Global Health: You mentioned the Cassandra curse, but what big warning signs currently stand out? What should people be watching?

Frieden: We would be mistaken in only preparing for one. I have simple rule of 10 million. What could kill 10 million people? Well, one is the next pandemic. The next pandemic will definitely come. The question is only what, when, where, and—further—how to reduce that risk. We need to systematically improve our ability to find, stop, and prevent health threats.

The other major pandemic, which isn't considered a pandemic, but is one, given that it already kills more than 10 million people a year, is high blood pressure. High blood pressure is underrecognized both as a major cause of cause of illness and death for the general public and as the single leading driver of disparities in survival and lifespan between white and Black Americans.

Think Global Health: Do any recent developments, either in the United States or abroad, further reflect the success and failure of communicating the importance of public health agendas?

Frieden: The major one is COVID-19. We've just come out of the biggest pandemic in 100 years, and, fundamentally, society can't agree on how bad it was. Yet, if we apply the formula, all of that is pretty clear.

In the United States, the glass is half full. The country prevented about half of the deaths it could have prevented, but about twice as many people could have died if we hadn't taken the actions we did take.

In the book, I discuss the issue of technical rigor: what it takes to know what's going to be effective. This is not so straightforward. To figure out where the truth lies, we have to go quite deeply into studies. We need to look at how things change over time: how our immunity changes, how the virus changes, how the tools that we use to fight it—including vaccines and treatment—change, and how we come to better understandings of the disease.

Certainty is the Achilles heel of science; using technical rigor, science searches not for immutable truths, but for better answers

When we look at COVID, we have to look at before and after the vaccine as very distinct periods. Before the vaccine, mortality rates were higher because people didn't have immunity from prior infection and doctors didn't know how to treat it effectively with simple, low-cost treatments. In that time, actions such as indoor closures made a big difference in tamping down spread so that hospitals weren't so overwhelmed and could provide better care for each of the patients affected, leading to fewer deaths. Once vaccination became available, the key was to deliver the immunizations to the most vulnerable, particularly older people, as quickly and as extensively as possible. The more rapidly that was done, the less frequently people died.

By following an accurate understanding of what was driving illness and death during the COVID-19 pandemic and by communicating effectively, states and countries that adhered to basic public health principles not only witnessed fewer deaths but also experienced less economic devastation.

In the book, I write that the mark of technical rigor and excellence in technical thinking isn't to have certainty, it's to have humility. The more we understand the details of a new disease, the more we can change our conclusions.

Certainty is the Achilles heel of science; using technical rigor, science searches not for immutable truths, but for better answers.

Think Global Health: You state that the most difficult part of the formula is the last piece: Create. Why do you believe this to be true?

Frieden: Creating a healthier future requires a systematic approach:

- organizing well, prioritizing, and simplifying, because complex approaches are rarely if ever scaled effectively;

- communicating; and

- overcoming barriers.

One driver of the Cassandra curse is the prevention paradox, which was first described by the wonderful public health expert Geoffrey Rose. The premise is that things that help a lot of people a little bit make a much bigger difference than things that help a few people a lot, and vice versa. This is part of seeing the invisible. For example, if public health teams reduce lead exposures by a little bit for millions of children, it has a massive impact. This outcome may be less visible or receive less news coverage than preventing a horrific case of lead poisoning in a factory, but the benefit is massive.

The challenge is the political corollary of the prevention paradox, which is that costs are often concentrated, whereas benefits are diffuse and delayed. Public health is almost inevitably going to have to fight against entrenched interests—farmers who don't want to give up their land for a reservoir system or the pharmaceutical industry that doesn't want to give up its profits to make medication more widely available. Another example could be the tobacco, alcohol, or junk food industries that want to keep selling products that make people sick.

In the past eight years, Resolve to Save Lives has worked in more than 50 countries to pass bans on artificial trans fat. More than 9 million people will not die young from a heart attack because of that program, but not one of those 9 million people will ever know that their life was saved by an international focus on getting rid of this invisible toxin from their food.

That is the crux of why creating a healthier future is so difficult and so important. We need to overcome barriers that are almost inevitable because of things like the prevention paradox that stack the deck against public health.

Think Global Health: You often mention the need for optimism. How would you suggest public health workers or anyone else in the health sector maintain optimism as science and medicine continues to be challenged?

Frieden: We have to keep perspective. I don't think we should be blind to the challenges, but there really are ample grounds for optimism. Now that doesn't mean that things aren't problematic at the moment, but we've seen a two-thirds drop in cardiovascular deaths between 1960 and 2010. Twenty million lives were saved in the United States alone.

Public health's curse is even worse than Cassandra's, because not only do people not heed warnings, but they also don't recognize the past progress that has occurred in society.

We're reluctant to talk about progress because it sounds like we're saying mission accomplished, nothing else needs to be done. To say that things are better isn't saying they're good enough. Identifying winnable battles and areas where we can make progress and cultivating optimism is important, especially when public health is in difficult times.

Facts are stubborn things. Even if they're denied, even if they're abused or suppressed, ultimately the truth will out.

Think Global Health: Social media has been a tool for effective communication but can also spread dangerous information. How do you recommend harnessing such a massive tool to combat growing distrust?

Frieden: One thing to do more often would be document the economic interests of groups that are spreading misinformation by selling ads or ineffective products. People have a lot of suspicions, and suspicion is justified because many things in our society aren't done fairly. Many businesses are able to treat their workers and their customers with impunity by hiding behind laws or regulations.

People in public health need to get better at understanding where people are coming from, addressing valid concerns, and showing a way forward to make clear that our only special interest is to increase healthy life.

Think Global Health: You mention the importance of real-life stories in the implementation of the formula because people become desensitized to the struggles of others as they are bombarded with images and information through news or social media. How can people harness the impact of real-life stories that reflect the existence of a crisis without feeding into the overload of information?

Frieden: We in public health may think in terms of numbers and tables and charts, but when we're explaining, it often helps to provide a human face. I tell the story of Terrie Hall, a wonderful woman. She was a cheerleader in high school, but also worked on a tobacco farm and started a two pack a day smoking habit. She developed horrible cancer in her 40s and died in her 50s, but after becoming ill really wanted to share her story. She became one of the best known of the real-life Americans who shared their suffering so that others wouldn't have to go through it in a series of campaigns called Tips from Former Smokers. Hers were so powerful that people would come up to her in the supermarket and say, "You got me to quit smoking" or "You saved my life." Terry probably saved more lives than most doctors will in their whole career.

Think Global Health: To wrap up, I want to pivot back to the current moment and the shifting public health landscape. Looking ahead 6 or 12 months, what might the ripple effects be, both negative and positive? What do you view as possible scenarios?

Frieden: I don't think anyone can predict the future. Some of the actions we're seeing now are extremely damaging and dangerous. In the long run, public health will come out stronger, but in the short and medium term, we're seeing wholesale destruction of lots of the public health infrastructure in the United States, and there's no silver lining to that.

The result of that will be more outbreaks and more preventable cancers, heart disease, and stroke. But it's also an opportunity for public health to say what we need to do to improve, to be more sustainable, to be more effective, to be better at understanding and conveying the most important messages.

When we as a society work together to implement the formula and overcome the forces and illnesses that block our paths, then each of us, our families, our communities, will enjoy healthier and longer lives.

AUTHOR'S NOTE: The Formula for Better Health: How to Save Millions of Lives—Including Your Own will be published on September 30, 2025 by MIT Press.