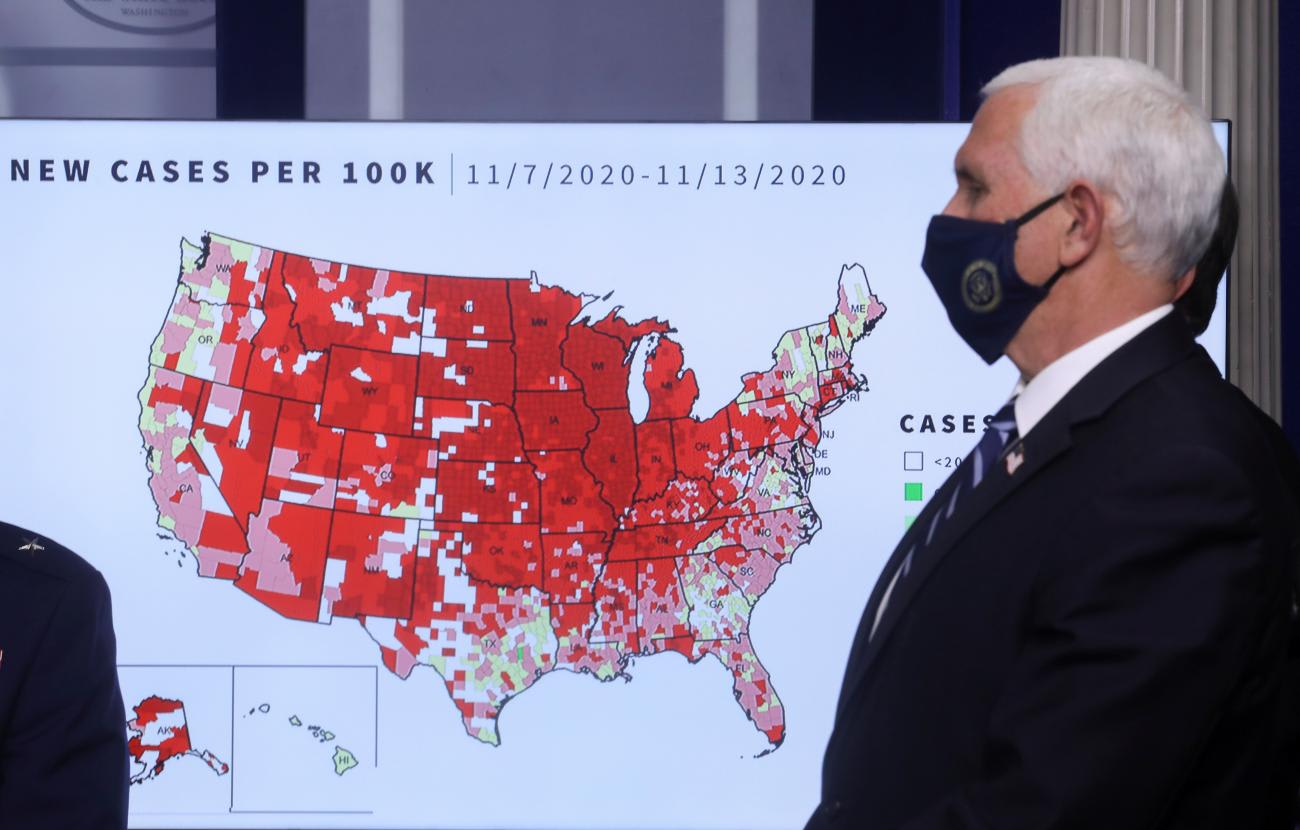

There is little disagreement that the U.S. response to the COVID-19 pandemic has been an abject failure. But few understand that a major contributing factor is the country's persistent coronavirus data crisis.

The latest analysis from the Population Council reveals that U.S. COVID-19 data remain fragmented and incomplete at national, state, and city levels, which conceals who is infected, where, why, and how they contracted the disease, and who is hospitalized and whether they live or die. This has left the U.S. government, health officials, and the public largely in the dark about how the coronavirus is infecting and killing people in their communities.

The Trump administration's lack of national COVID-19 data strategy, politicization of data reporting, and sidelining of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) are partly to blame. But it also reflects the country's persistent failure to invest in a resilient routine surveillance data system and data expertise at local health departments.

We are encouraged by the Biden-Harris administration's new COVID-19 national strategy, which promises to be guided by science and directs federal agencies to enhance the collection, production, sharing, and analysis of data to support an equitable response and recovery. However, given inequities that have already emerged in COVID-19 vaccine distribution and ongoing challenges in data collection, this strategy needs to be accelerated and include investment in accurate, real-time data and an integrated data system that flows form local health departments to the CDC.

The Population Council's latest report builds on previous analyses that comprehensively reviewed COVID-19 data reporting and analysis across fifty states, Washington DC, and ten major cities. We assessed data completeness using the CDC case investigation form, determining whether each state or city reported on COVID-19 testing and outcomes (cases, hospitalizations, recoveries, and deaths) and disaggregated these by five demographic indicators (age, sex, race/ethnicity, geography, underlying conditions). By disaggregating COVID-19 testing and outcomes in these ways, health officials can understand the profile of individuals who are getting tested and infected as well as their disease trajectory, and deploy an effective trace, isolate, and treat strategy.

Our latest analysis shows that the United States is still failing to capture and analyze basic COVID-19 data and equity indicators in a consistent and comprehensive way, resulting in a fragmented and incomplete data system.

Incompleteness and Unstandardized Data

As of the end of 2020, fifty states and Washington, DC had barely half of the total data completeness score of 17 out of 30, reflecting almost no improvement over previous assessments months earlier. The ten cities exhibited similar patterns, and no state or city had complete data.

Overall Data Completeness Across 50 U.S. States and DC

COVID-19 cases and deaths were most commonly disaggregated by demographic indicators. Hospitalizations and recoveries have consistently been underreported throughout 2020. This is a troubling pattern as hospitals in the United States are facing a crisis-level shortage of beds and staff. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services hospital capacity data do not include demographic indicators, which makes it difficult to get a full picture of who is hospitalized or experiencing adverse outcomes within any given community.

Furthermore, states and cities continue to employ varying definitions for core outcomes and indicators, and different methodologies for data collection, which makes it cumbersome to identify all available data points.

Inadequate Equity Data Related to COVID-19

Social and economic disparities faced by communities of color exacerbate their overall health conditions and put them at greater risk for COVID-19 infection and severe disease. The Biden-Harris administration committed to "protecting those most at risk and [advancing] equity, including across racial, ethnic and rural/urban lines." This is pivotal, as age-adjusted mortality rates show that COVID-19 is killing Black, Latinx, Indigenous, and Pacific Islander communities at more than double the rate of whites and Asians.

In our analysis, only twenty-six states and five cities had established a task force to address health disparities related to COVID-19 — an improvement from fifteen states and four cities in August. But only thirteen out of the thirty-one states and cities mention data collection.

COVID-19 Equity Data and Task Forces

Furthermore, almost all states and cities failed to report and analyze certain basic equity indicators such as gender identity, poverty levels, and ethnicity. Another worrying trend is that only thirty-four of the sixty-two states and cities conducted intersectional analyses – the examination of how multiple risks interact to affect COVID-19 outcomes, a slight decrease from August.

In recent months, states improved in their reporting of occupational and community level data. As of December, 25 of fifty states reported on healthcare worker status, forty-one on the types of residence, and twenty-four on places of exposure. But the data remain inadequate for shedding light on COVID-19-risks associated with people's occupations and living arrangements, which hinders effective contact-tracing and support as well as vaccine distribution.

Throughout the pandemic, federal government agencies have relegated data responsibilities to local health departments, which have long been under-funded and poorly resourced, with overburdened staff often using paper-based data collection methods. Little has been done to mandate data-reporting.

Having accurate, reliable, real-time, open data is a fundamental part of a disease prevention and control strategy. The federal and state government must take seven tangible steps to rectify the U.S. coronavirus data crisis:

- CDC and the White House COVID-19 Task Force should deploy a national COVID-19 data strategy and work with health departments to strengthen data systems for a more structured and standardized approach to collecting, reporting, and analyzing COVID-19 testing and outcomes as well as sociodemographic indicators.

- The White House COVID-19 Task Force should lead the integration or triangulation of routine COVID-19 surveillance data, hospitalization capacity data, and vaccine distribution data.

- Local health departments should invest more resources in strengthening capacity for data collection, reporting, and analysis to reduce the burden on an already stretched workforce.

- Policymakers should invest in user-friendly data reports that link to data resources on a single webpage, simplify the types of data resources, and present all data in a coordinated way at the local, state, and national level.

- Communities should make COVID-19 data openly available, invest in data analytic expertise, and collaborate with external scientists.

- Communities should establish COVID-19 equity task forces to collect more comprehensive data and tackle inequities based on the findings.

- CDC and the White House COVID-19 Task Force should leverage other federal agencies, such as the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, to incentivize more robust data reporting through reimbursements and receipt of relief funds.

Investment in strengthening data systems and expertise is critical. Having the right data can arm the new administration and health officials with insights to guide local and national officials to prevent and contain outbreaks while mass vaccination efforts are underway. Moreover, it can pave the way to building a more resilient and responsive surveillance data system that can prepare the United States for future epidemics.