The incredible global progress over the past two decades in reducing the burden of HIV/AIDS may be at risk. Billions in global health funding for the disease propelled a reduction from 1.95 million deaths in 2006 to 954,000 deaths in 2017. Despite these successes, some places like Eastern European countries have seen their epidemic increase. Further, the pace of decline in new infections globally is not on track to meet UNAIDS targets. Continued progress in reducing HIV burden may hinge on addressing the social, cultural and political responses to the disease.

AIDS deaths in 2017—down from 1.95 million in 2006

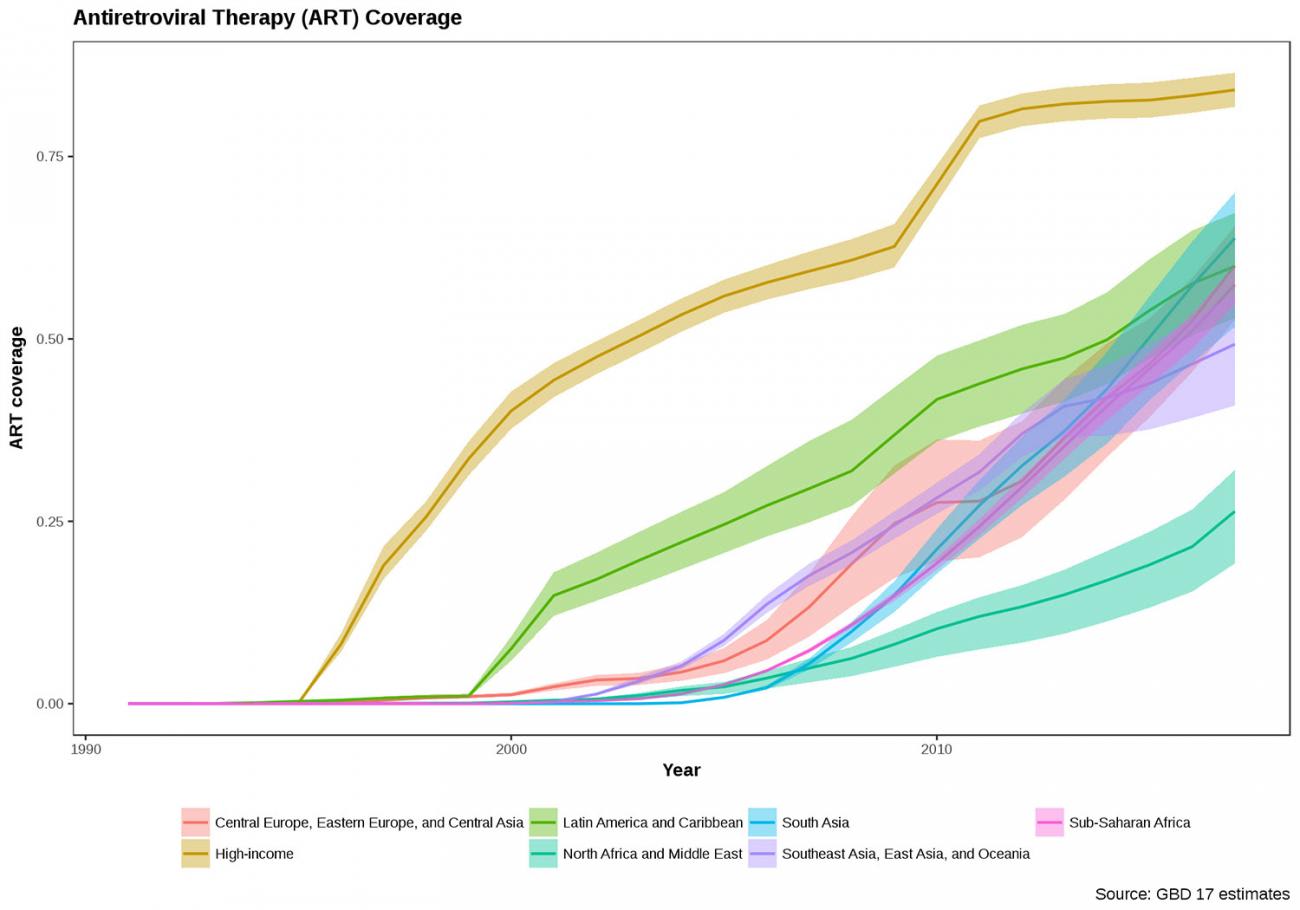

Underlying the large-scale funding for HIV/AIDS intervention in 2000–2009 were commitments to improve the general level of administration, health services, and availability of treatment. The advent and rollout of antiretroviral drugs as well as countrywide initiatives for prevention helped transformed HIV/AIDS from a death sentence to a manageable chronic disease. Since 2006, sub-Saharan African countries collectively reduced their estimated number of potential years of life lost due to HIV/AIDS from 87 million to 39 million in 2017. This was in large part thanks to the coverage of antiretroviral therapy, which increased dramatically around the world.

Those who could more easily be targeted and who could more easily access the opportunities for testing, services, and treatment benefitted the most. Now, with the fifth decade of the pandemic almost upon us, it's time to ask what it will take to sustain progress.

The disease's shift towards higher risk groups may be stalling progress to eliminate HIV/AIDS. Connections to testing and treatment and public acceptance of targeted services is more difficult in groups such as men who have sex with men.

The stigma around HIV/AIDS is not new.

The social and political response becomes more contentious when the general public does not necessarily readily accept providing free treatment coverage to particular groups. For example, Botswana is debating merits to providing free treatment coverage to immigrants including migrant sex workers, recognizing that it cannot otherwise eliminate HIV. New challenges are also emerging that involve injection drug users. In Ukraine recently, injectable drug users of a new substance, Krokodiles, were found to be at greater risk of HIV. A rise in HIV in West Virginia has been tied to opioid use, and a recent JAMA opinion piece describes the increasing drug use in rural communities as a threat to ending HIV/AIDS in the United States.

An approach that addresses the needs of higher-risk populations is likely required for further gains in reducing the burden of HIV. The stigma around HIV/AIDS is not new. However, we should recognize that our continued success hinges on confronting challenges related to prevention, testing and treatment among more politically-contentious groups at high risk for the disease. The emergence of treatment-resistant strains and evolving global socioeconomic vulnerabilities compound the risk of casting historically stigmatized groups aside. Without addressing these challenges head-on, proliferating concentrated epidemics will prevent achieving the ambitious incidence reductions set out by UNAIDS and create a simmering pot for more general rises in HIV incidence and mortality in the future.

EDITOR'S NOTE: The author is employed by the University of Washington's Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), which leads the Global Burden of Disease Study. IHME collaborates with the Council on Foreign Relations on Think Global Health. All statements and views expressed in this article are solely those of the individual author and are not necessarily shared by their institution.