If the emergence of the omicron variant of COVID-19 teaches us anything, it is the truth behind the words, "This pandemic is not over until it is over everywhere." Scientists across the world have worked to give us the tools to manage and reduce the impact of this pandemic, yet the fact that we still have such inequity in vaccination access is testimony to the fact that we, as a "global community," are not in the right place to cope with such a crisis. Nor will we be for the next one unless we completely change our approach to and funding of global preparedness.

Despite an increasing supply of vaccines, we see that in many of the poorest countries, health and research and development (R&D) systems are totally inadequate to serve the needs of their populations. This inequity affects everyone. While some are fortunate to live in countries with effective health research and development systems that can ramp up their responses to such emergencies, many are not. This R&D inequity lies at the core of current and future lost lives. Dame Sarah Gilbert, Saïd Professor of Vaccinology at the University of Oxford who led the development of the Astra Zeneca vaccine, said recently, "Imagine the lives and costs that could be saved if we could always work at the pace we have done for COVID-19." And she called for ongoing preparedness for future global crises related to pandemics and to climate change.

Imagine the lives and costs that could be saved if we could always work at the pace we have done for COVID-19

Professor Dame Sarah Gilbert

Regrettably, the "global" health community usually has a standard answer to such a plea and that answer is both short-term and narrowly focused. At the beginning of the pandemic, expectations of global science cooperation involving low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) were high, but as time passed, reality revealed that research and product development were largely confined to high-income country institutions and businesses. While vaccines resulting from this R&D were meant to be "shared" with LMICs through initiatives such as COVAX, supplies have remained inadequate. In June, COVAX forecast that roughly 1.9 billion doses would be distributed by the end of 2021. They revised that forecast down to 1.4 billion in September. If we compare with what they had originally promised, COVAX has shipped 0.74 billion doses, or 39 percent. Even those that were delivered could not always be fully used due to short expiration dates and delivery system problems.

In addition, despite the effort to generate enormous financial resources to conduct research to prepare for diseases with pandemic potential, one of the largest global research responses is mostly about sharing the outputs rather than integrated development of R&D systems in LMICs. It seems that, once more, there is no plan for the strategic and on-going development of R&D ecosystems in LMICs as essential parts of pandemic preparedness.

Vaccine inequity is morally wrong and a major obstacle to containing the COVID-19 pandemic. Its continuation more than two years into the pandemic also clearly shows the limits of global solidarity as an effective global public health strategy. For many decades, most LMICs have depended on the scientific, industrial, and financing efforts of high-income countries to address their R&D and innovation requirements. Investments in their own R&D ecosystems have been low in many LMICs. It seems obvious that a continued reliance on gifts does not solve the long-term problem of inequitable participation in effective R&D and resulting interventions.

The two biggest current threats to global health security—pandemics and climate change—require equitable access to R&D and implementation. "Facts, data and science are the most effective tools available," U.S. Secretaries Antony Blinken and Xavier Becerra wrote recently. Achieving R&D equity should therefore be considered as an urgent, essential, and pragmatic preparedness strategy to improve the global R&D ecosystem's capability to prevent and abate future pandemics and other global challenges such as climate change.

Building R&D Equity

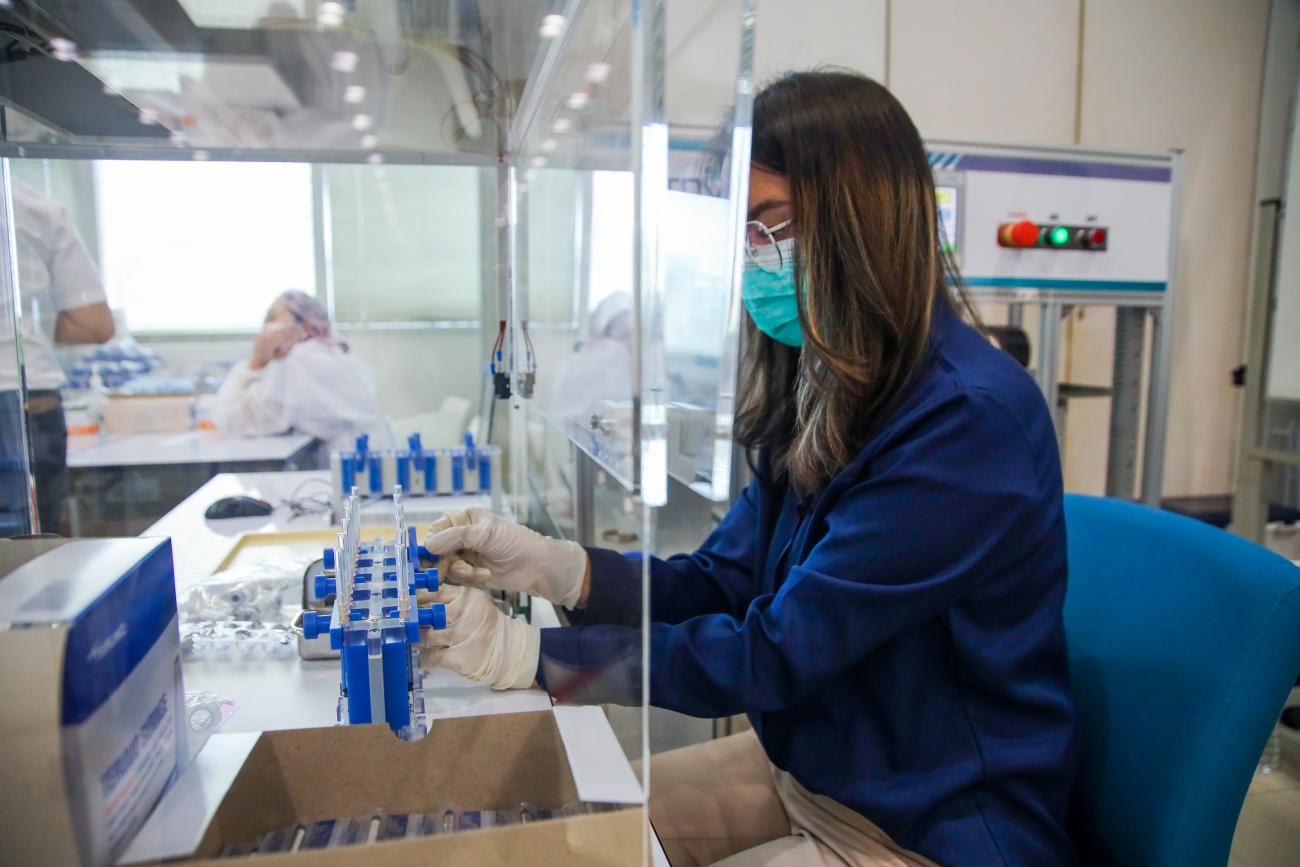

Besides international collaboration and an initial demonstration of global solidarity, the COVID-19 pandemic has also demonstrated that middle-income countries that have made sustained and serious investments in their own R&D ecosystems—including China, India, South Africa, Senegal, Cuba, and Thailand—are now playing an important role in pandemic control. Twenty years ago, their potential contribution to pandemic control would not have been considered. Now, their vaccines and manufacturing capacity are key to vaccinating most people in LMICs. This achievement is insufficiently acknowledged, but it proves that building R&D ecosystems can make a significant difference in local and global preparedness for both pandemic control and climate change adaptation.

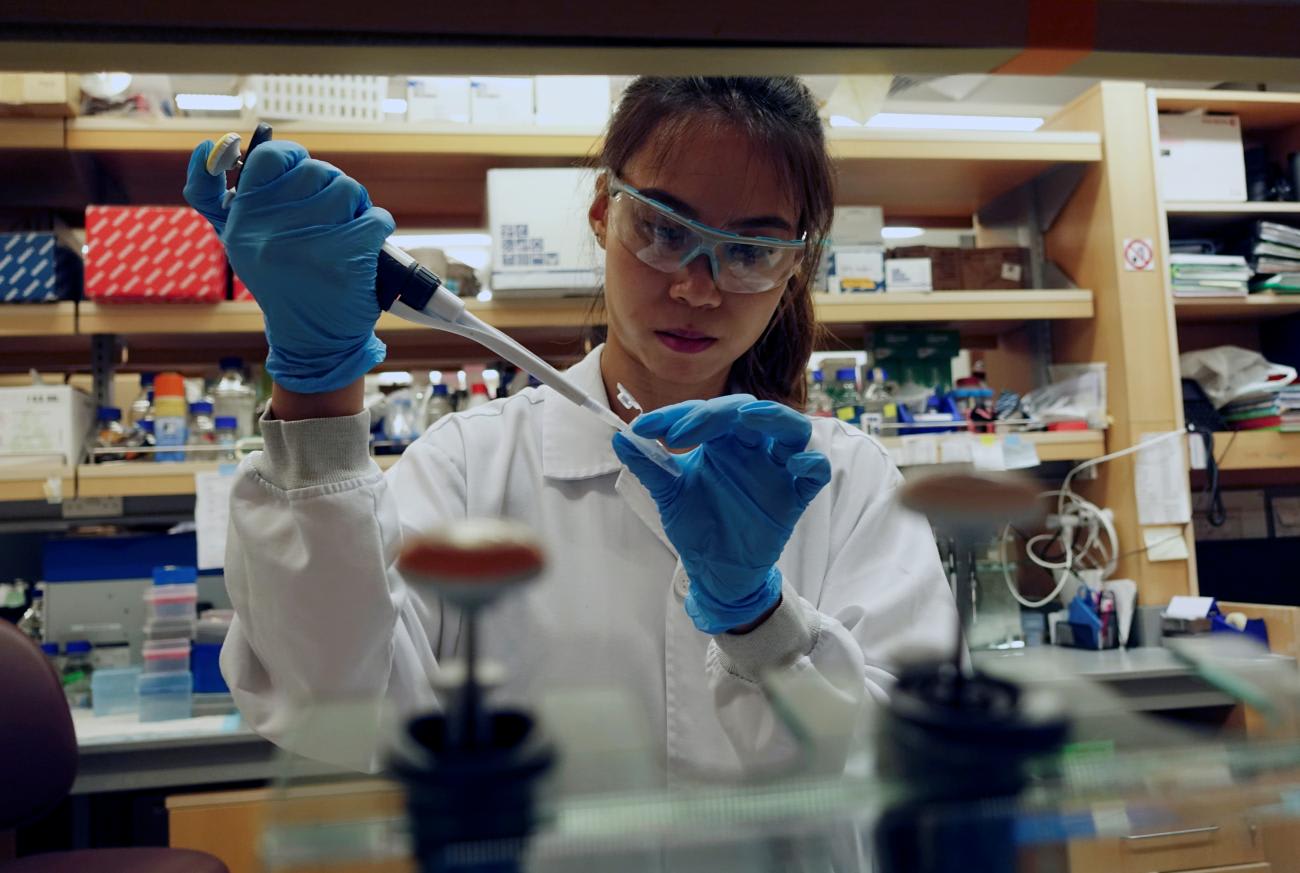

An R&D ecosystem is complex and multifaceted, on the one hand, and accessible to change by any country, on the other hand. For COVID-19 control, advanced virology and laboratory infrastructure and trained personnel are required for research, development, and implementation of innovations that will end this pandemic. At the same time, competencies in contracting, financing, procurement, communication and education, negotiation, social science research, intellectual property management, health systems development and many other aspects are all crucial parts of any capable R&D ecosystem, and can be acted upon by any LMIC as part of local and global prevention and control.

While increasing vaccine production capabilities may end the supply shortages for LMICs in the near future, issues such as distribution, cold-chain, and uptake need to be addressed as well, so they do not become the next bottlenecks facing the R&D ecosystems, particularly in resource-constrained settings. "Vaccine inequity" should not become "vaccination inequity."

For many, the idea of R&D ecosystem strengthening is too vague, too long-term, and too "political"

Can R&D Equity Really Work?

For many, the idea of R&D ecosystem strengthening is too vague, too long-term, and "too political" to even consider, especially in the middle of a pandemic. However, we believe that there are three main arguments which demonstrate that investing in R&D equity is vital and can actually work for the future benefit of all.

First, enhanced capability locally will support preparedness globally. The example of COVID-19 vaccine production in LMICs shows that R&D equity has the potential to be an operational framework to achieve full local engagement in preparedness and control of current and future global challenges. R&D equity can be designed as a pragmatic approach to encourage and enable any country, no matter how low on any development index, to act, participate and contribute to development of its own R&D ecosystem.

LMICs want to take the initiative and spend own budgets on local preparedness. African political and health leaders, frustrated by the lack of vaccine sharing and low vaccination rates, have become serious about efforts to focus on own vaccine production. For years, LMIC investments in their own R&D ecosystems have been low. The new willingness to engage R&D is apparent in many LMICs and this should change the way high-income countries engage with LMICs—working together in a more collaborative way.

Most importantly, technology is helping to achieve R&D equity. The revolution of the new mRNA vaccines is not limited to its flexibility and design options. A lesser known but no less important advantage of mRNA vaccine technology is that vaccine production has become easier, requiring less and less complicated infrastructure than what is needed for traditional vaccine development. This makes vaccine production in LMICs more possible—and it may lead to more vaccine design and adaptation in LMICS.

The time is ripe to include R&D equity as an explicit objective in national and international development and collaboration policy.

Being prepared for pandemics and for the multitude of consequences and impacts of climate change will require actions in many fields and by many actors, sustained over decades. An often overlooked component is a competent and flexible global R&D ecosystem—one that is truly global and includes all countries and regions. The COVID-19 pandemic provides a salutary wake-up call for the need to invest in R&D ecosystems worldwide.

When reviewing the requirement for the next director of the NIH, an op-ed by the editors of Nature said, "Now the world's leading biomedical research body must position itself to tackle many other problems—chronic disease, health inequality, and the health dimensions of climate change—for which solutions have so far remained stubbornly out of reach."

Including R&D equity as an explicit component of all international collaborations between high- and low- and middle-income countries is essential. LMICs that are not yet investing in their own R&D systems need to begin doing so at the risk of remaining dependent on ineffective global efforts. High-income countries need to support LMICs interested in developing their national and regional R&D ecosystems as an essential aspect of global preparedness.

AUTHOR'S NOTE: The authors would like to thank Salim Abdool Karim, Centre for the Aids Programme of Research, in South Africa, Congella, South Africa; Charles Mgone, Hubert Kairuki Memorial University, in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania; and Marleen Temmerman, Aga Khan University, in Nairobi, Kenya for their assistance in preparing this article.