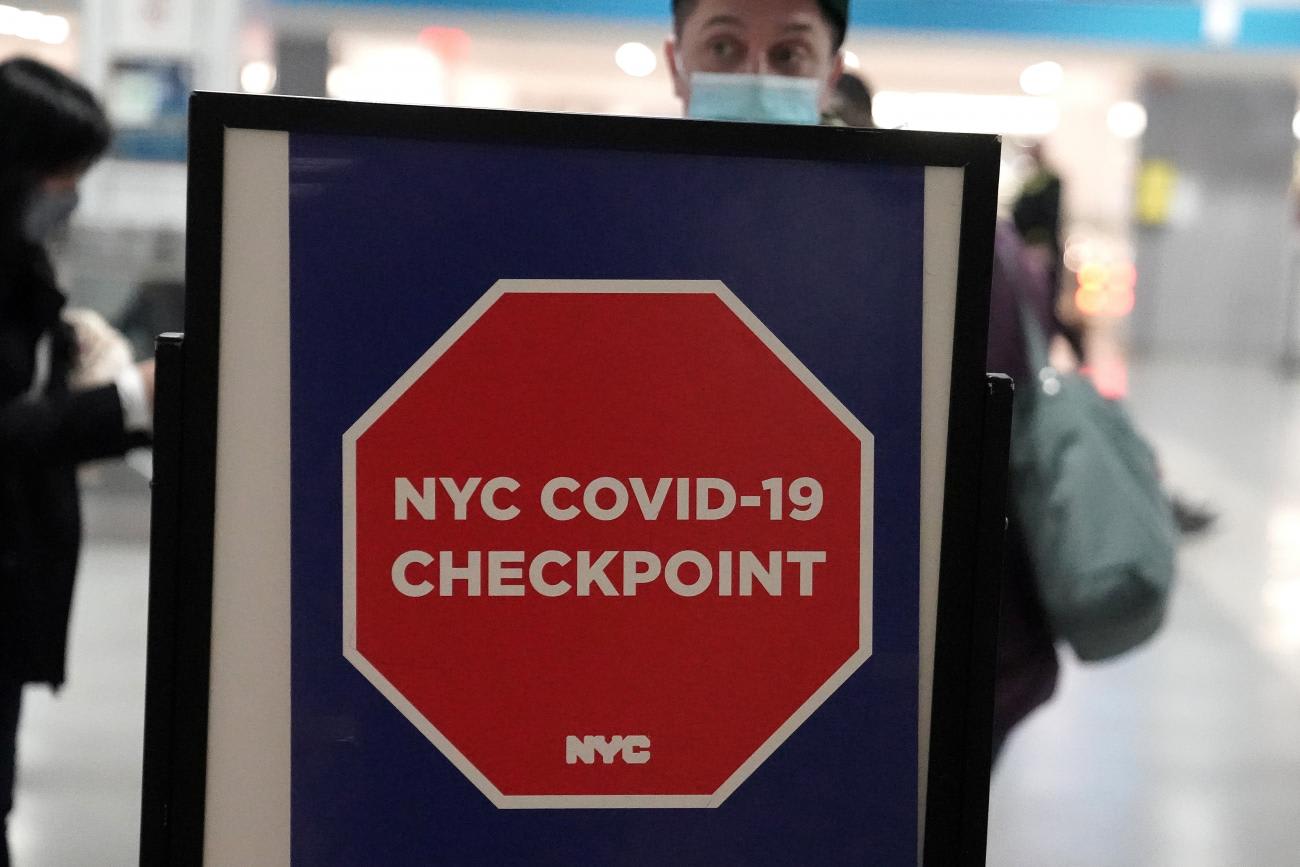

On March 1, 2020, New York City recorded its first confirmed case of COVID-19. Within two months, more than 177,490 cases had been reported and 18,879 people had died, making COVID-19 the deadliest disaster in New York City since the 1918 influenza pandemic. One year has passed, and as we emerge from the recent winter surge and face the possibility of yet another this spring, it is useful to look back on those early days of the outbreak to understand what went wrong, and how we can do better.

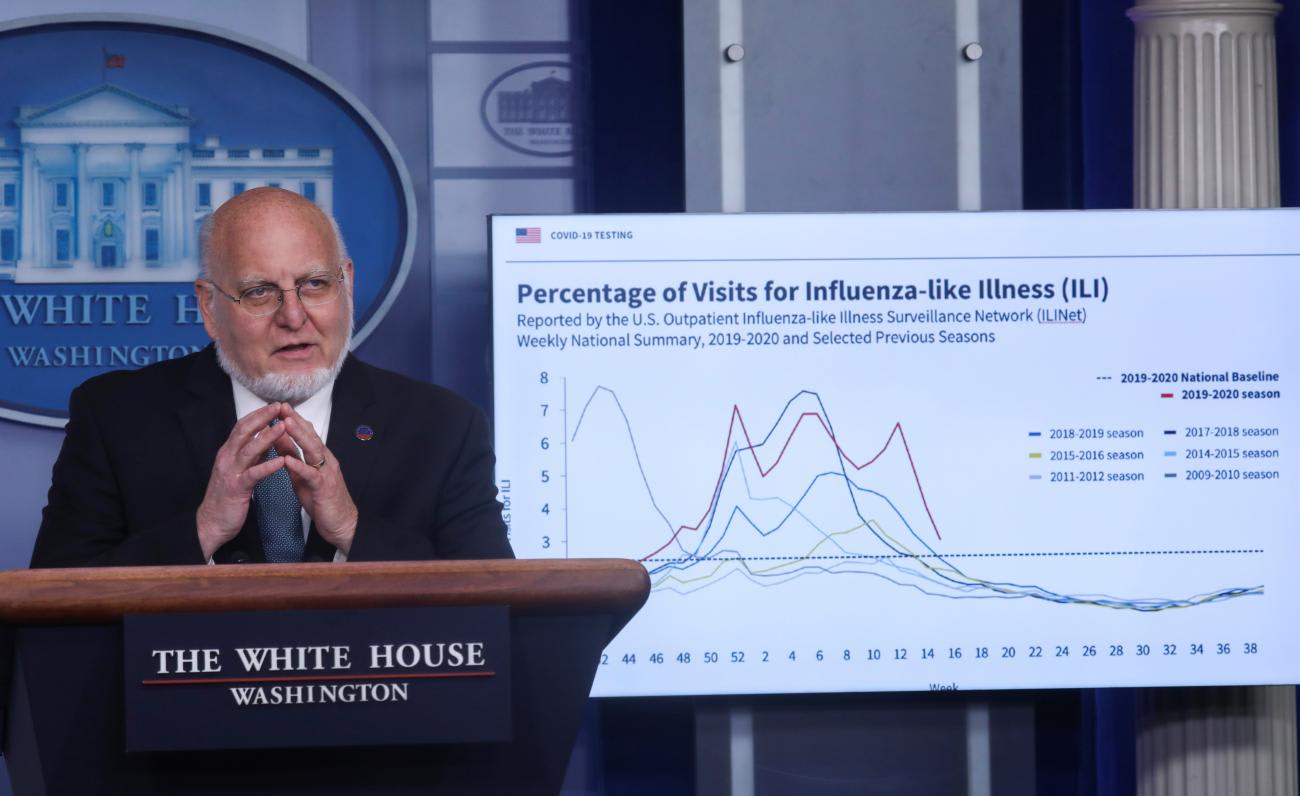

Public health officials and policymakers have already pointed out familiar failings. In a recent interview, former CDC director Dr. Robert Redfield attributed delays in the U.S. pandemic response to a lack of cooperation from the Chinese government and their failure to disclose important information on person-to-person transmission. An independent task force report sponsored by the Council on Foreign Relations, in which I took part, identified a number of other missteps, including the failure to implement a national strategic plan paired with an underbudgeted, overburdened public health system.

Our failure to monitor and respond to the spread of COVID-19 came from a communication breakdown about the case criteria

As an emergency physician on the front lines in New York City, I can add a simpler explanation: our failure to monitor and respond to the spread of COVID-19 came from a communication breakdown about the case criteria. This impacted all aspects of our frontline operations, from who we could test to when we could wear personal protective equipment.

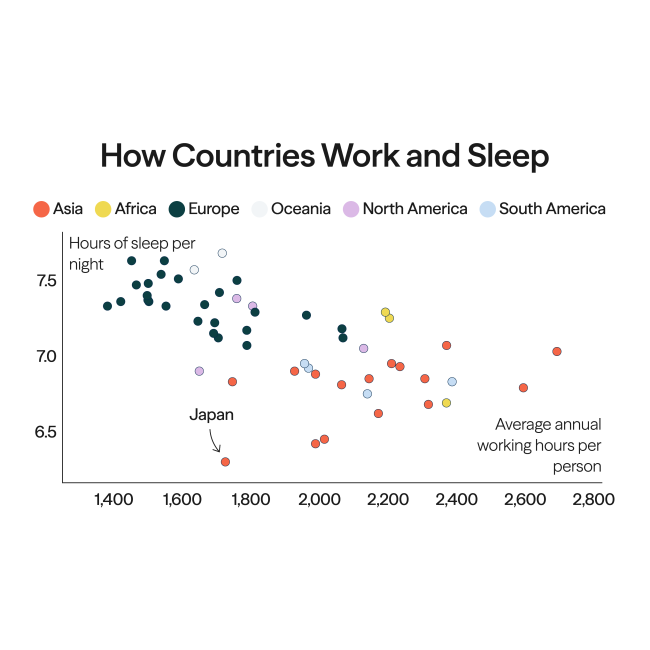

New York City's COVID-19 surveillance is a case in point. Even after the World Health Organization declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern on January 30, 2020, the city failed to ramp up testing for COVID-19. Throughout February, clinicians could not order a test without authorization from the state Department of Health, in strict accordance with case criteria set by the CDC: only symptomatic patients with significant travel history, or those who had close contact with a laboratory-confirmed case of COVID-19, could be tested. During this period, the number of New Yorkers with influenza-like illness presenting to emergency rooms and urgent cares was increasing while true influenza cases were decreasing—data indicating the potential presence of COVID-19 transmitting in the community.

Many frontline providers recognized these trends and wanted to test patients but were caught in a catch-22. We could not test patients with flu-like symptoms who did not have the prerequisite travel history unless they had close contact with a confirmed case—nor could we confirm a case without first testing our patients. By the time a nurse returning from Iran was diagnosed at Mount Sinai Hospital on March 1, 2020, the city's first recorded case, only ten people had been tested for COVID-19 in New York City. Ten people, in the country's most populous metropolitan area, an international transit hub with multiple flights arriving daily from countries already known to be experiencing community transmission of COVID-19.

One year later, we continue to live with the consequences

The gaps in our surveillance created by the case criteria lead to further disconnects in contact tracing, masking, and physical distancing. If a patient did not qualify for testing based on the case criteria, then they were not considered persons under investigation for COVID-19—which meant they were not isolated, their contacts were not quarantined, and their clinicians were not advised to wear personal protective equipment. Even after the CDC amended the case criteria on March 4, 2020 waiving travel requirements and expanding testing to a wider group of the population at risk, emergency physicians and nurses in New York City were routinely treating patients presenting with chills and body aches and sore throats without using masks or respirators. And after our busy shifts, we would leave the hospital and board the subway, hoping to find a seat amid rush hour crowds on the long ride home to our families. One year later, we continue to live with the consequences.

These repeating and compounding errors related to the case criteria originated in a failure to communicate. The patterns emerging in New York City during February of last year, which were raising alarms along the front lines, were also recognized at the highest levels of our public health institutions—Dr. Redfield acknowledged being worried about the rise in flu-like illnesses even as true flu positives fell. Yet there was little to no communication about these shared concerns between our top public health officials and our frontline providers. As a result, there was no change in the case criteria, and patients remained untested. By the time the World Health Organization declared a pandemic on March 11, 2020, we were already in widespread community transmission of COVID-19 in New York City. Later, other bottlenecks in testing emerged, such as a lack of available and reliable testing kits, insufficient laboratory capacity, and a scarcity of personal protective equipment, but these were not the initial barriers to our pandemic surveillance in New York City.

By the time the WHO declared a pandemic, we were already in widespread community transmission of COVID-19 in New York City

Asked how to better prepare for the next pandemic, Dr. Redfield suggested that local health systems like Mount Sinai Hospital be ready to develop and deploy their own tests. This illustrates another fundamental disconnect between our larger public health institutions and the realities of frontline medicine. Implementing a testing strategy that even partially subverts guidance from the CDC would be difficult to rationalize let alone operationalize. If not explicitly stated in the case criteria, it would be hard for any hospital to justify testing beyond what is recommended by the CDC.

Dr. Redfield also advocated for greater investments in public health. This is the correct answer—but for the wrong question. Yes, we need to restore funding to our local health departments, improve our testing and contact tracing capacity, and invest in vaccine and treatment innovations. These recommendations are all necessary but insufficient for meeting the immediate challenges of an emerging pandemic, and they fail to address the breakdown in lines of public health communication.

Out of necessity, frontline providers found a solution to this communication breakdown: talking to each other. In New York City, emergency physicians are collaborating on improving our pandemic preparedness by revisiting our experiences with the first wave of COVID-19 and re-envisioning a health system capable of withstanding the next. We meet weekly to discuss previous and current challenges, and to share best practices on how to effectively manage our COVID-19 patients. We also convene on social media groups with other emergency physicians across the country and around the world in order to get and give clinical guidance, and to support each other. Through these networks we also have a heads up on potential hotspots when we see warning signs of an oncoming surge. Essentially, we have created a powerful COVID-19 surveillance tool for ourselves.

We are looking back, learning from our mistakes, grieving our losses, and moving forward together

These support mechanisms are crucial now more than ever as hospitals continue to face severe budgetary shortfalls and cutbacks in their emergency departments—in effect, decreasing our frontline capacity in the middle of a pandemic. Emergency physicians will make do as we always have, but it requires multi-level, multi-sector collaboration, and clear, consistent communication within and across our health systems. One year from the front lines in New York City, this is the greatest change we have made to our practice. It is making a difference in the lives of our patients—and also our fellow providers. We are looking back, learning from our mistakes, grieving our losses, and moving forward together.

EDITOR'S NOTE: The author would like to thank the following frontline providers for their contributions: Marwah Abdalla, Albert Arslan, Nita Avrith, Nicholas Caputo, Cheryl Chang, Makini Chisolm-Straker, Louis Cicatelli, Jennifer Fernandez, Tsion Firew, Tamer Kamash, Marc Kanter, Ben McVane, Nina Ragaz, Karin Rhodes, Les Roberts, Charles Sanky, Fereshteh Sani, Elizabeth Singer, Craig Spencer, Deepti Thomas-Paulose, Ben Wyler, and members of the Emergency Medicine All Threats group.