Monkeypox infections in Nigeria are on the rise. In June and July alone, the country confirmed more than 130 cases—more than six times the number of infections recorded in the first five months of 2022. While official figures are likely undercounts due to challenges health authorities in Nigeria have had monitoring disease transmission, what is more concerning is Nigeria's difficulty containing the spread of the virus and providing care for patients.

Alongside the recent monkeypox outbreak, Nigeria is still managing the repercussions of the country's COVID-19 health crisis. The underfunded public hospitals across the nation are struggling to cope with an influx of patients in a country where malaria, HIV/AIDS, and Lassa fever continue to spread and challenge the health system. To make matters worse, less than a year after a two-month strike, some physicians are threatening to stop working at a time when the country's 40,000 doctors are already unable to adequately cater to its 200 million people.

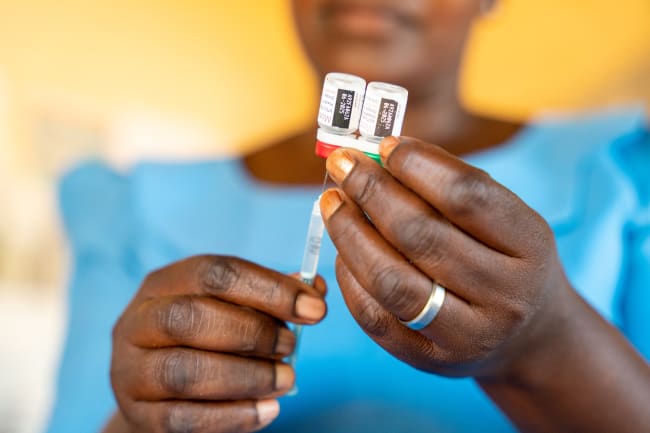

Combined with Nigeria's overstretched health systems, poor monkeypox surveillance and limited access to monkeypox vaccines could create a public health disaster as infections continue to climb. The total number of confirmed cases in the first seven months of 2022 is higher than the number of confirmed infections during the previous four years—from 2018 to 2021—combined. And the West African nation's vaccine program is one of the weakest among countries battling monkeypox outbreaks.

Overstretched health systems, poor monkeypox surveillance, and limited access to monkeypox vaccines could create a public health disaster

Since the United Kingdom discovered its first case in early May, it has procured about 130,000 monkeypox vaccine doses for at-risk persons. Just last week, the European Commission's Health Emergency Preparedness and Response Authority (HERA) said 109,090 doses of monkeypox vaccine had been procured since the outbreak began, with Spain receiving 5,300 doses. In that same time period, the United States has shipped more than 602,000 doses of Bavarian Nordic's JYNNEOS monkeypox vaccine—with the hardest hit areas receiving more than 100,000 doses.

Here, in Nigeria, no such measures have been reported. Currently, there are no monkeypox vaccines or antivirals available in the country. Speaking at a public health conference in June, John Oladejo, director of Health Emergency Preparedness and Response at the Nigeria Centre for Disease Control (NCDC), said the agency had begun "active surveillance" and that new cases were being "treated immediately" with patient contacts being monitored for symptoms. But there have been reports of outbreaks in communities where official figures show only one or two confirmed cases.

The NCDC has reported 413 suspected cases and 157 confirmed cases from twenty-six states between January 1 and July 31. But unlike in Europe and the United States, Nigeria's monkeypox outbreak didn't begin this year, it started in 2017. And if you sum up the number of cases in the last five years, it amounts to about 925 suspected cases and 383 confirmed.

"The actual figures are likely much higher than what has been officially recorded considering the fact that surveillance hasn't been too effective, especially in conflict areas," said Collins Anyachi, a physician with the Department of Family Medicine at the University of Calabar Teaching Hospital in Nigeria's southeastern Cross River State. "Because of challenges with surveillance, monkeypox infections could be growing in some communities and no one knows anything about it."

The challenges with surveillance are clear. Health-care workers are unable to reach affected areas due to armed bandits and militants, and the reluctance of families and communities—especially in rural areas—to report suspected cases to authorities for fear of stigmatization. These factors all contribute to a deceptive case count. Along with extenuating social circumstances, the COVID-19 pandemic also drastically reduced the surveillance of monkeypox. With more cases going unreported, public health officials fear that once the disease infiltrates the country's poorest neighborhoods, overcrowding and poor sanitation could cause rapid community transmission. This, combined with the slow and unorganized responses by local governments could create a public health disaster.

If vaccinations don't begin immediately, it may become very difficult to implement vaccination in the future due to bandits and terrorists who continue to expand their operations across the country, said Anyachi, who has worked as a physician in conflict-hit north-central Nigeria in the past. "The longer it takes [to roll out vaccines], the more people get infected and that could be disastrous."

But even if Nigeria were to improve its disease surveillance and procure monkeypox-specific vaccines and treatments, it is unclear whether citizens would be willing to get vaccinated. Since the monkeypox outbreak began in Nigeria, there has been widespread disinformation surrounding its actual origin and fake news about children being administered harmful vaccines by health authorities. Similar disinformation has spread about COVID-19, affecting vaccination against the virus in Nigeria, and only 11.6 percent of the population is fully inoculated.

The international outbreak of monkeypox has highlighted the disease as a public health threat, and has brought much-needed attention to the smoldering monkeypox outbreak in Africa. If nothing is done to improve access to vaccines and treatments across the continent, Nigeria, Africa's most populous nation, could experience a monkeypox disaster.

EDITOR'S NOTE: Follow our monkeypox timeline for the latest developments in the 2022 monkeypox outbreak.