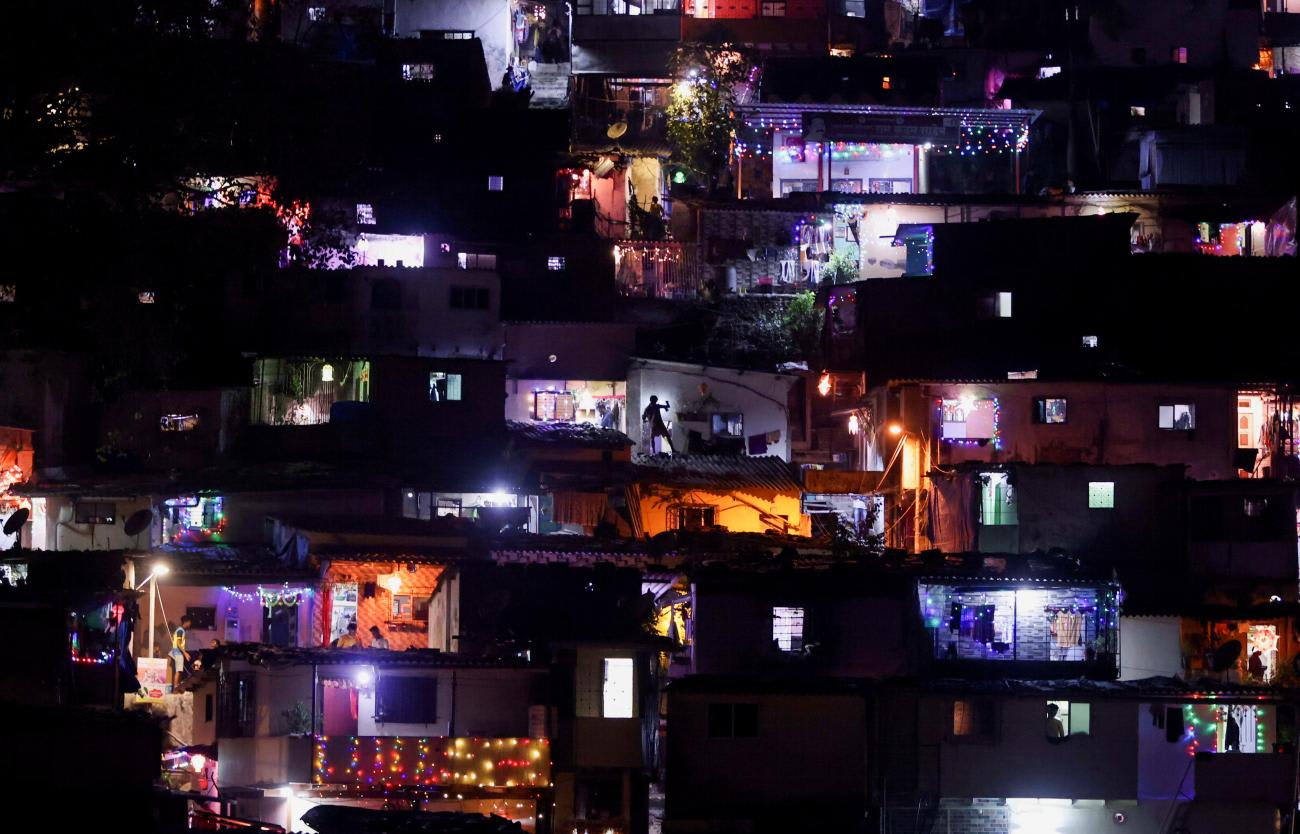

It was my first job after graduating from medical school. I worked as a pediatrics house officer in a primary care hospital serving the Bandra slums of Mumbai during the COVID-19 pandemic in India. One night during a late-night shift, I received a call from a delivery room nurse that a post-term mother, gestation age of 42 weeks, had been admitted and was taken for an emergency Caesarean section.

When pregnancy is carried beyond 40 weeks, the risk of fetal and newborn complications, including stillbirth and respiratory problems, rises. The baby was born at 11:30 p.m. He had a faint heartbeat but was not breathing. I, along with other members of the resuscitation team, tried to revive the baby by supplying oxygen through a tube down the throat, multiple adrenaline injections, and chest compressions. The baby died at 11:48 p.m. It was the first time I witnessed a newborn death; I was disheartened and shocked. The senior anaesthetist tried to comfort me and exclaimed, "One dead Muslim, one less terrorist in the world."

I worked as a pediatrics house officer in a primary care hospital serving the Bandra slums of Mumbai during the COVID-19 pandemic in India

The health-care crisis due to the pandemic had converted most government or public hospitals in the region into "COVID-only" hospitals. These hospitals were not permitted to care for or admit patients who were COVID-19 negative; you could not enter the hospital if you did not have a recent laboratory report showing the virus in your nasal or oral cavity. During this crisis, my hospital became the only public "non-COVID" hospital in the region.

Bandra, one of the most affluent areas in India, is home to movie stars, powerful politicians, and multinational companies such as Deloitte, Accenture, and Infosys. Among these affluent societies, there are massive slum areas neglected by the city's redevelopment projects, which serve as waste dumping grounds by the city. During my eighteen months of service in the hospital, I discovered that most so-called "slum dwellers" were Muslim immigrants from other parts of India and other countries, including Bangladesh and Sri Lanka. People living in these areas suffered from inadequate housing and sanitation, lack of social security, and severe poverty.

The UN framework for the immediate socioeconomic response to COVID-19 stated: "The COVID-19 pandemic is far more than a health crisis: it is affecting societies and economies at their core. While the impact of the pandemic will vary from country to country, it will most likely increase poverty and inequalities at a global scale." Apnalaya, an NGO empowering the urban poor in Mumbai, conducted a rapid assessment to study the impact of COVID-19 and the lockdown on a slum community. They found that 91.8 percent of people who had paid work before the lockdown were unemployed during it, and 87 percent reported no income source. They did not have social security, and the lack of income jeopardized peoples' access to food, water, health care, transportation, and other basic needs. In addition to these social challenges, their health care conditions deteriorated during the lockdown.

The slum community's antenatal care was poor and worsened during the lockdown as pregnant women feared attending the hospital and the risk of COVID-19 infection. Many were unable to attend due to a lack of public transport. We often had women coming to the hospital in the final stages of their labor who had not received prenatal care. As a result, it was not uncommon to have complicated deliveries and neonatal problems after birth.

The demands on our hospital increased as we became the only public non-COVID hospital in the region. The non-COVID illnesses thrived as they did before the pandemic. However, the government did not proportionately increase the supply of essential resources such as medications, oxygen cylinders, and personal protective equipment. Health-care staff were asked to work overtime without a proportionate increase in their pay. They felt dejected that they were not being rewarded for risking their and their families' lives. There was an air of burnout and frustration among the staff in the hospital.

When our hospital's administration requested additional funds and resources, they were denied as the requirements of dedicated COVID-19 hospitals (DCH) were prioritized. Indian health care went through an oxygen shortage during the pandemic, and hundreds of patients died in DCHs. Our hospital also had an oxygen shortage problem. There were only two oxygen cylinders in the newborn and pediatric wards. One oxygen cylinder would last around 30 minutes or less when used in the high-flow setting.

I was staggered after hearing that inappropriate remark by the anaesthetist. One of the nurses agreed with him and said, "One oxygen cylinder was wasted on a lost cause." She continued, "That Muslim woman already has six children. Why does she want one more if she cannot take care of the baby properly?" They blamed the mother for coming late, not getting antenatal care, and lack of family planning. As the newest and most junior team member, I nodded while fighting back the tears of sadness and anger.

Often, women who had not received prenatal care came to the hospital in the final stages of their labor

Research has shown that many non-Muslims, especially in the West, label Muslims as violent individuals who support terrorism. Chandra and his colleagues analyzed tweets during the COVID-19 outbreak and found a growing association between the Muslim community with the COVID-19 pandemic. The Indian media raised questions about the intentions of a Muslim gathering in Delhi, the Tablighi Jamaat, held before the lockdown was imposed. This negative media coverage of Muslims led to the public, and social media, labeling them as "COVID super-spreaders" and accusing them of spreading COVID-19 in India to infect Hindus. The dynamics of the Hindu-Muslim relationship have been complicated since India's partition in 1947.

The pandemic-instigated Islamophobia and discrimination against Muslims significantly influenced public health. Islamophobia has been associated with poor mental health, suboptimal health behaviors, and unfavorable health care-seeking behaviors. Islamophobia was a potential source of adverse health outcomes and health inequalities during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The following day, I went to the postnatal ward to talk to the 22-year-old mother and inform her of what had happened to her child. I introduced myself and asked her what she already knew. She told me her baby died because she came late to the hospital. The nurse had a chat with her before I arrived. I asked her about antenatal care and family planning. She told me that Anganwadi workers (health and social care workers) used to visit her community weekly to inform her about antenatal visits and childcare, however, they had stopped coming after the lockdown. Her husband worked as a construction worker in the Middle East and could not travel back because of the lockdown. Therefore, she did not have anyone to take her to the hospital for antenatal check-ups. I asked her not to blame herself as it was not she who failed her child but the health system.