Exhausted mothers leaning against the hard tiles of railway station walls, cradling babies and toddlers in their arms. University students from Africa and India clutching backpacks and cell phones, trying to catch rides out of a now war-torn country. Children's faces peeking from the windows of buses and trains heading to European cities.

These are just some of the images of the more than one million people the UN says have now fled their homes, workplaces, and schools in Ukraine since Russian troops began invading the Eastern European country a week ago.

The numbers are staggering right now—they seem to go up every hour

"The numbers are staggering right now. They seem to go up every hour," says Rachel Levitan, vice president of international policy and relations for HIAS, a global nonprofit organization that focuses on protecting and resettling refugees in partnership with the Ukrainian organization Right to Protection.

Their health, safety, and relocation needs are staggering, too. There are multiple nongovernmental organizations stepping in to provide care and resources, explains Adrianna Murphy, associate professor of Health Services Research and Policy, and co-director of the Centre for Global Chronic Conditions, at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM).

"The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) will coordinate the refugee response with other UN agencies. They will work with implementing partners who will actually deliver care, including organizations like the International Red Cross, Médecins Sans Frontières, and the International Rescue Committee," she says.

Right now, humanitarian groups are focusing on providing people arriving at the borders of neighboring countries with a mix of first aid, shelter, food, and water—basic needs—and even SIM cards, so people can stay in touch with family, said Birgitte Bischoff Ebbesen, the regional director for Europe at the International Federation of the Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, who spoke at a press conference this week.

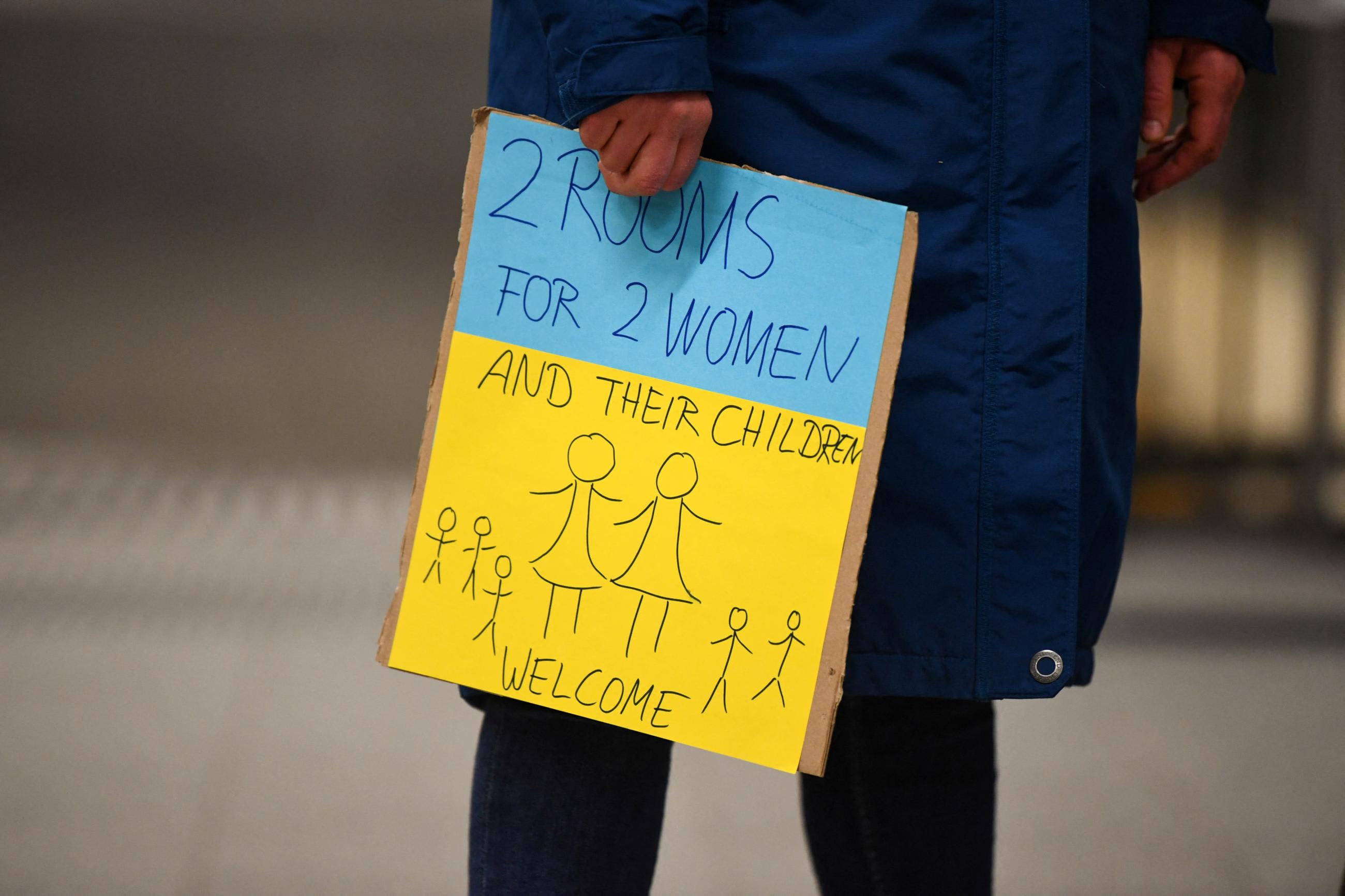

At the borders, she said, "Our special focus will be on unaccompanied minors, single women with children, and seniors." She noted though that they also have volunteers currently in bomb shelters assisting people still in Ukraine.

But despite immediate needs being met, the situation is "incredibly tense, dangerous, and distressing," said Martin Schüepp, regional director for Europe and Central Asia at the International Committee of the Red Cross, who also spoke at this week's press conference. Some of the most vulnerable are the hardest hit.

"Our Red Cross team is reporting people in despair… there is significant emotional distress and trauma," Schüepp said.

In the days ahead, the Red Cross and other humanitarian organizations hope to open up humanitarian corridors—which Ukraine and Russia have agreed to—where people fleeing and the injured can move or be moved safely.

"What these refugees are facing, it's really just the beginning of the journey," says Talia Inlender, deputy director of The Center for Immigration Law and Policy at the UCLA School of Law.

Flooding to Ukraine's Borders

Bordering Ukraine to the west and south are Poland, Slovakia, Hungary, Romania, and Moldova—all of which are taking in refugees. Poland has by far the most people pouring across national lines, says Kristof Veres, a senior researcher at the Hungarian Migration Research Institute (Migrációkutató Intézet), who is also currently an Andrassy national security fellow at the Center for Immigration Studies, in Washington, DC. The UNHCR reported close to 650,000 arrivals at the Polish border as of March 3, with Hungary receiving the second largest number of people, at 144,738.

Refugee Arrivals from Ukraine to Bordering Countries

Among the crowds seeking refuge in nearby nations are many who are not from Ukraine— including students, workers, athletes, and visitors from Africa, Asia, and the Middle East—but who were in the country when war broke out. There are 18,000 students from India alone in Ukraine. So far, 4,000 have crossed into nearby countries, escaping the Russian invasion. A fourth-year medical student from India tragically lost his life in Kharkiv when he left a shelter to buy food for others.

Thousands of students from Africa study in Ukraine, as well. The African Union published a statement this past week on the reported ill treatment of Africans trying to leave the embattled nation, calling for everyone to have "the same rights to cross to safety from the conflict in Ukraine, notwithstanding their nationality or racial identity."

Red Cross staff and other humanitarian organizations now working in Ukraine border countries were prepared for this emergency. Mesfin Teklu Tessema, senior director of health at the International Rescue Committee (IRC), says Poland had been readying for a possible influx over recent weeks.

"We have been monitoring the escalation of this conflict since early February, so we had a team deployed in Poland early in the first week of February to monitor as well as prepare," he says.

Doctors Without Borders/Médecins San Frontières has also been setting up emergency response activities in border nations, dispatching teams to Poland, Moldova, Hungary, Romania, and Slovakia.

American officials estimate that ultimately, up to five million people from Ukraine may seek protection in neighboring countries in the coming weeks and months, and they say U.S. troops are now in Poland helping Polish forces establish processing centers for those arriving.

Reaching the Border, Then What?

At the borders, there are miles-long queues—mostly women and children. It can take up to two days to get through. Many need health care by the time they reach the front of the line, after long treks in cold weather. The elderly and other vulnerable people are especially at risk for health complications.

"The immediate health needs of refugees generally, and of Ukrainians, are those things that require regular access to health care—antenatal care, treatment of chronic communicable diseases like TB and HIV, and that of chronic non-communicable conditions like hypertension or diabetes," says Murphy.

Safety is also a major focus for humanitarian groups. "We are trying to make sure there is adequate space, that there is no risk of gender-based attack—especially for women and girls," says IRC's Teklu Tessema.

For the most part, Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia have completely opened their borders to refugees from Ukraine, says Veres. After identification checks are made, people are registered, given phone numbers for agencies that can help, medical care, food, hot tea, and blankets, and then they await transportation to major European cities, Veres says.

In Hungary, people can travel for free on a train reserved for refugees to Budapest and when they arrive there, government agencies and NGOs will help, first determining if they have relatives or know someone in Hungary, and if not, connecting them with relatives and friends in any other EU country and arranging transportation. If they don't have contacts, then agencies arrange accommodations for them.

"It was a totally different process before the war," says Veres.

COVID-19 transmission is of deep concern to global health experts. LSHTM's Murphy said this refugee crisis is unique because it is happening while Eastern Europe is still in the midst of the pandemic.

"Before Russia invaded, Ukraine was seeing 25,000 new cases each day. Only 40 percent of Ukrainians are vaccinated and many refugees are traveling in crowded buses, trains, or other vehicles. It's possible that the COVID-related care will become important," Murphy adds.

COVID-related medical supplies and oxygen are critical, says IRC's Teklu Tessema. "The country was running out of supplies, and the World Health Organization (WHO) and others have actually donated quite a lot. I think we saw that oxygen supply arrived in Poland to be shipped to Ukraine. So that's the kind of thing that is needed so that people who need medical treatment can get it so they don't have to die of preventable causes," he says.

Longer-Term Health After Displacement

In forced displacement crises, people are often traumatized, says Levitan. "From listening to Ukrainians in the last couple of weeks, it was clear that people were not expecting this. They did not have their bags packed. Many now feel like they're reliving the traumas that their parents and grandparents experienced during the Second World War," she says.

Among those displaced due to the ongoing conflict between Ukrainians and Russian-backed separatists in the eastern region of Donbas, as of 2019, between 17 to 32 percent suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, and anxiety, Murphy said. And almost three-quarters of those were untreated.

Mental health and psychosocial support will be critical not just for people who've left Ukraine, but for people who are still there, including humanitarian staff who will have witnessed Russia's full-scale attack on Ukraine, which has targeted civilians, neighborhoods, hospitals, and university buildings, among other locations.

Teklu Tessema is extremely concerned about supply chain disruptions and the massive upheaval of health services there, including the medical care that will be needed for the wounded.

"These are some of the health challenges that we are looking at and we think health services should be protected in these times of crisis to make sure that people continue to receive care," he says, noting that attacks on hospitals are a violation of international humanitarian law.

Medications to treat the most prevalent conditions and diseases in Ukraine—hypertension, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease—will be needed. "Untreated, they can cause severe health consequences, or death," Murphy says.

"The longer this drags on, the more widespread and intense the need is going to get," says Judy Twigg, professor of political science at Virginia Commonwealth University. If this crisis stretches out, she adds, listening to health personnel on the ground in Ukraine and at the borders is going to be critical.

"Listen to what they need and where they need it. And work with established organizations," says Twigg, who notes that sending cash to verified humanitarian organizations can buy what they need, when they need it, and it is more useful than collecting and donating blankets.

WHO has a long established, important presence in Ukraine and will be doing a lot of coordinating, serving as an information clearing house for things that are needed. Whether or not WHO should cut ties with Russia is being debated by many leaders and health experts.

Twigg says, "WHO should reassess its relationship with Russia immediately, especially some of its higher-profile partnerships like the WHO European office on non-communicable diseases in Moscow."

EDITOR'S NOTE: Relief organizations from around the world are on the ground in Ukraine and neighboring countries. Established organizations accepting donations include: the International Committee of the Red Cross, International Rescue Committee, Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières, and Ukraine Humanitarian Fund.