One month after a new Ebola outbreak was reported in the east African nation of Uganda, a World Health Organization (WHO) official said this week that the outbreak is "rapidly evolving." We spoke with emergency room physician and Ebola survivor Craig Spencer, associate professor of the practice of health services, policy, and practice at Brown University School of Public Health, to learn more about the latest outbreak, which has infected sixty people and caused twenty-four deaths, according to Uganda's Ministry of Health.

□ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □

Think Global Health: What do we know about the current Ebola outbreak in Uganda?

Craig Spencer: Uganda declared an outbreak on September 20, 2022. But it's likely that Ebola was circulating for weeks or months before it was recognized and confirmed. There is no surprise that there is Ebola in Uganda again—there have been multiple outbreaks there. What was concerning was how quickly it grew. It became in the top half of all Ebola outbreaks in size just within a few weeks. Now, it seems to have slowed down somewhat. But it's not clear if that reflects the true reality of the outbreak.

Think Global Health: Is the slowing down a good sign? And are there certain regions where spread is a bigger concern at this time?

Craig Spencer: It's a waiting game to see what's going to happen with this outbreak. Five districts have been impacted so far. Health activists there have been primarily focused on Mubende [a town in the central region of Uganda]. They are working with the Ministry of Health of Uganda to set up treatment facilities, and to set up case management and tracking.

Think Global Health: Is it a multi-pronged effort or is one entity taking the lead?

Craig Spencer: WHO and other actors are setting up epidemiological tracking. It's been pretty clear the Uganda government and Ministry of Health wants to be the lead on this and is directing and is really out front.

Other groups like MSF had been in the country beforehand, so they're there building treatment centers and involved with management of disease. WHO, MSF, and the Health Ministry of Uganda are doing the majority of the work. It's been made very clear here that the Ugandan government is leading the charge.

Think Global Health: Can you talk a bit more about the government's choice to lead the charge?

Craig Spencer: Uganda has managed multiple outbreaks in the past. They have experienced Ebola before. But not just with Ebola. They've had many other infectious threats in recent history. They clearly have the experience, and many [people in Uganda] are much more comfortable having the Ugandan government manage it. Obviously, it's critical that you have local leadership and buy-in.

We've seen in most other large outbreaks that responses are coordinated by international groups. But people will say, "They're selling our bodies, using them for witchcraft, the international community is using us." Not having a big panoply of humanitarian actors at the forefront may stem some of those rumors, misinformation about the virus, and resistance [to disease prevention and vaccination] by the community.

Think Global Health: Is there a downside to the government running the response to this outbreak?

Craig Spencer: We have to recall that a militaristic response has been used in Congo, and in Sierra Leone and Liberia to enforce quarantines. So there has to be some balance between what's needed to get outbreaks under control and what's going to be beneficial to do that. But both international and local governments can make mistakes.

Uganda declared an outbreak on September 20, but it's likely that Ebola was circulating for weeks or months before it was recognized and confirmed

Think Global Health: How should the global health community get involved, if at all?

Craig Spencer: There are a couple of big things. We know there has to be community involvement. We know this: every lesson learned from every Ebola outbreak says we should have involved the community more. It needs to be understood what the socio-cultural impact of Ebola has on a community, not just the big picture [of eradicating the virus].

We also need to recognize the risk of spread to neighboring countries could be potentially catastrophic. Uganda is much more prepared for Ebola, than for example, South Sudan next door. There have been some alerts there but no confirmed cases.

Burundi doesn't have, historically, infrastructure to deal with Ebola, so they need to have the testing capacity. And testing that provides results back within a day or two, as opposed to five or seven days when you're sending tests to labs in South Africa for results. The countries that haven't scaled up yet need to be prepared to respond early.

Think Global Health: How is testing capacity going in Uganda right now?

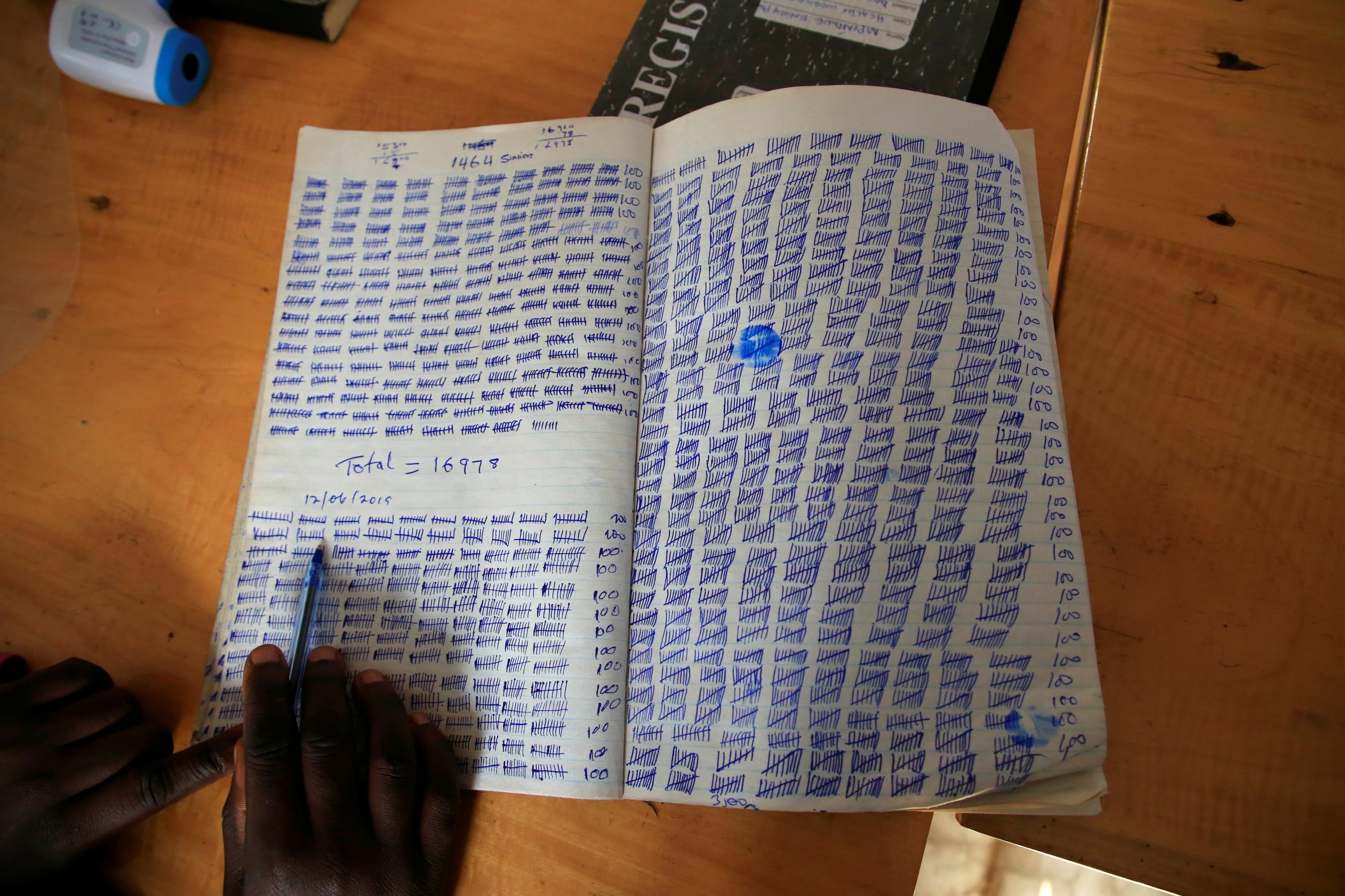

Craig Spencer: Within Uganda, it sounds like there has been an increase in testing at the central government facility and at the Ebola treatment center is in Mubende. With Ebola, we've learned you need to scale up testing more than you think. Especially swabbing all burials for Ebola. That requires a huge amount of infrastructure.

Think Global Health: Why are burials sites of concern?

Craig Spencer: Every single person that died in West Africa, we swab. They are given an Ebola test to make sure they haven't died of Ebola. In West Africa, we saw burial practices are a big spreader of Ebola. "Witch doctors" were big spreaders.

Ebola is often called a very contagious disease, but it isn't. But if you're preparing someone for burial and cleaning them, that's dangerous. WHO has been sure to monitor burials.

Think Global Health: How can people in Uganda and other countries avoid infection?

Craig Spencer: The majority of things we do [hygiene-wise] on a daily basis work. If you just wash your hands, you're going to be quite safe. It's contagious in certain settings: burial settings especially.

Also, being a health care provider, especially without gloves, is dangerous. And making sure health care providers use personal protective equipment (PPE) is critical. PPE aren't helpful unless they're used correctly and correct use is going to cut down on the majority of transmission. There has been a big focus by the international community, by the United States, to be sure there is enough PPE. And then it's a question now of how variably and well-implemented they are.

Think Global Health: You've had personal experience with Ebola. Are you concerned about reinfection?

Craig Spencer: I had Ebola Zaire in 2014. We cannot say for 100 percent certain, but I've never heard of someone being infected by Ebola twice. We believe being infected once provides long-term protection against reinfection against the same species of the virus. It's extremely unlikely, if not impossible, that I would be infected with Ebola Zaire again. Would I be infected by Ebola Sudan, the species in Uganda right now? It's reasonable to expect Ebola Zaire antibodies don't work for Ebola Sudan.

We often had people who recovered and helped take care of other sick people. And we have seen that a very small number of people who have previously been infected can harbor the virus for a long time, and later have re-emergence of the disease. This is what lead to a new outbreak in Guinea recently.

Think Global Health: Are certain types of patients more at risk for death from Ebola?

Craig Spencer: Kids don't do well. In my experience, it was basically a death sentence in children under five with Ebola Zaire. But, among the last cases in Guinea a newborn survived—we don't know why. If we saw a kid under five or someone over sixty, your baseline mortality was already really high.

Think Global Health: What is the status with Ebola vaccines?

Craig Spencer: We know that the two vaccines used against Ebola Zaire were quite effective. In populations that were exposed to the virus, the vaccines were incredibly successful. But it has been a challenge to get those vaccines to people.

In terms of the vaccine candidates for Ebola Sudan, the Sabin Institute is working on one and there are one hundred doses available, and the hope is that they can scale up to the thousands in November. For the few candidates that do exist, we don't have as much safety and efficacy data on them yet as we would ideally like.

Think Global Health: The U.S. said earlier this month saying that all travelers coming from Uganda would need to enter through one of five airports and be screened. Should travelers worry about Ebola?

Craig Spencer: People who are very sick with Ebola likely aren't going to be traveling. I'm less concerned about our capacity to respond here in the U.S. Gloves, hygiene, etcetera, will help prevent Ebola in any of our institutions. I was a little disappointed in the travel screening notice—that it wasn't accompanied by what we're already doing in Uganda and should be doing in other places—providing material and logistical support.

We saw a lot of stigmatization with earlier outbreaks. We saw from the last Ebola outbreaks, that we need to fight this at its source. Travel bans aren't going to help if this thing isn't addressed in communities.

We're giving funding and U.S. support in terms of logistics and resources. But this is a different species of the virus. The one thing I always try to focus on is we've fought many outbreaks before Ebola, yet we often repeat the same mistakes over and over again despite the fact that these outbreaks are happening again and again. We focus on biomedical imperatives versus social phenomenon. Community engagement is often not at the forefront of our responses. In those initial weeks, the contact tracing and testing is really important. But having anthropologists, trusted community leaders, and religious leaders, can help. Ebola was stopped in Liberia because communities took matters into their own hands

There's been a lot of concern over the past few years about how we'll respond to another COVID-19 pandemic—or the next pandemic. I think the way we respond to Ebola outbreaks is indicative of that.