For more than thirty years, Paul Farmer has been a pivotal figure in global public health. Partners In Health, the nonprofit he cofounded as a medical student in 1987 along with Ophelia Dahl and Jim Yong Kim, today has 18,000 staff and delivers basic health care to people across three continents. His writings, which draw on his experiences as a clinician and medical anthropologist and make arguments of crystalline moral clarity, have shaped generations of students.

No stranger to epidemics—his most recent book, Fevers, Feuds, and Diamonds, is part memoir, part history of Ebola in West Africa—he endured COVID-19 largely locked down, but was involved in public health responses both in the United States and abroad, even as he continued to advance a longer-term public health agenda around the world. He spoke about his work and life with Think Global Health.

□ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □

Think Global Health: What were your expectations at the outset of COVID-19, and how did they compare to what actually occurred?

Paul Farmer: Everything that I feared would happen has come to pass. People want me to say, “I was so shocked by the spread of COVID in communities of color and essential workers”—and I wasn’t surprised by any of it. How could I have been? I’ve spent more than 30 years thinking about, studying, responding to, and taking care of patients who face either epidemics or pandemics. What other pandemic has not followed these patterns, using social inequalities and disparities to get into the human body?

What other pandemic has not followed these patterns, using social inequalities and disparities to get into the human body?

The real shocker for me will sound very suspect in some public health circles, and that was the mRNA vaccines. The mRNA vaccines just blew me away, and they still do. We have tools that we never had before, and I'm trying, like a lot of people, to focus on their promise.

Think Global Health: The vaccines are undeniably a triumph, but I’m a little uneasy about the major success of this being purely technological. It rubs the public health person a little bit the wrong way.

Paul Farmer: I share your anxiety and discomfort. If less than 1 percent of the vaccines have gone to poor people in poor countries, we’re just screwed unless we have new ways of thinking about how to come up with billions of doses. I just think, well, what are our options? To fight on the outside, or to fight on the inside, or try and do both. And I’m trying to do both.

Think Global Health: Contact tracing is one of the foundational public health responses to infectious disease. Can you touch on your experience with it and its use during the COVID pandemic?

Paul Farmer: I actually first learned about contact tracing in Haiti, but my first job after starting medical school was as a contact tracer in Massachusetts. I was hired by Ed Nardell, a friendly professor who was also the director of tuberculosis control for the city of Cambridge and later other posts. (I still work with him). And because I spoke Haitian Creole, I was on the Creole-speaking outreach team to do contact tracing around tuberculosis.

So, when the COVID outbreak started, [co-founder of Partners In Health, and now Vice Chairman of Global Infrastructure Partners] Jim Kim was quick to say we should use the kind of public health lessons we’ve learned everywhere in the world here in the United States: contact tracing, social distancing, etcetera. And what surprised me was not the need for it, but the willingness of the governor of Massachusetts to invest so heavily in it.

I can’t say, “Wow, it was a perfect experience.” But what would that curve have looked like without contact tracing and, most importantly, an effort to provide supportive isolation? The idea that people can suddenly just stop their jobs, essential or not, and be in a hotel room for two weeks—there has to be an infrastructure for that. So, we set that up. And I say “we,” as in Partners In Health.

Think Global Health: But some contact tracing efforts that were widely touted were overwhelmed by the scale of infection going on in the United States.

Paul Farmer: No question. If you look at China, you knew that they would have a different kind of trouble, but not the same one we did. They would be able to impose a contact tracing regimen, and a distancing regimen that we would not.

I like living in the United States, but this pandemic is the kind of crisis for which the United States is uniquely unprepared. Divesting in public health, no national safety nets, and wild disparities.

So, I’ll just say I’m very proud of my colleagues for what they’ve done, not just in Massachusetts but in Illinois, in Ohio and Florida, in the Navajo Nation, in Los Angeles, in Newark. I’m really proud of them, and I can only speculate, as an American who’s seen the uniquely poor performance of the United States in responding to the pandemic, that it would have been even worse without those efforts.

Think Global Health: It is disheartening to see the best laid plans crash on culture and governance, which seem inviolable.

Paul Farmer: Well, I think we have to fight back. What we see again and again is a strain of clinical nihilism, very much like what I started to hear in my Harvard Medical School classes in 1984: “It’s not cost effective to care for people, it’s not sustainable to care for people.”

Everything to do with care was a pie in the sky. I didn’t know back then about the history of colonial medicine, particularly in Africa—that policy in colonial medicine all along was to ignore clinical care for the natives and focus on disease control and protect investments.

I don’t see clinical nihilism that much in the United States. For example, it would be hard to say, “You’re from Brooklyn, therefore the standard of care is different for you than in Manhattan.” People do think that, but it’s hard to say and not get called out on it.

"What I saw in the United States over the last 15 months wasn’t clinical nihilism; it was containment nihilism"

But what I saw in the United States over the last 15 months wasn’t clinical nihilism; it was containment nihilism. It reached its apogee when the president himself fell sick with COVID, and his chief of staff Mark Meadows said, “We’re not going to stop COVID in the United States through containment measures. We’re going to stop COVID in the United States through medical measures and vaccination.”

And in fact, that’s exactly what happened, because things that get said in the White House have a way of becoming prophecies, self-fulfilled...it should have been different.

Think Global Health: Right now, there is the sort of prophetic expectation about the observed inequality in who has access to the vaccine worldwide. How are you fighting against that?

Paul Farmer: Partners In Health has 5,000 people working in Rwanda, and I lived there 10 years, and two of my kids were born there. There, we’ve seen firsthand what happens when a government recognizes that we should think of a health care delivery system as being both about prevention and care, and then invests 20 percent of their public budget in it—the highest share on the continent. What we’ve seen over the last 15 years are the steepest declines in mortality ever documented in any place in the world at any time.

So, when COVID hit, one of the first things I started to talk about with friends in vaccine production, public health, basic medical science—in pharma, too, when we could get them on board—is how can we start vaccine production on the continent? And what better place than Rwanda—organized, efficient, serious about anti-corruption. How can we get that up and running there?

You need financing, you need manufacturing capacity, you need tech technology transfer, you need political will. It will require not just a TRIPS waiver, but real collaboration with one of these companies that can share the wherewithal and knowhow to do it.

I just got back—I was there last week—and they’re pretty gung ho. And, at least Pfizer and Moderna aren't attempting to block that, as far as I can tell.

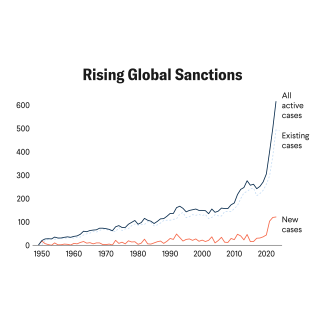

If you look at a map of opposition to TRIPS waivers and a map of colonial rule, it's the same map: every country in Africa said, “We’re for this,” and pretty much all the European countries said, “We’re against it.” And the big question to me was, what about our country? I’m pretty proud that for the first time, we didn’t go through that stupid fight that came about with HIV drugs.

I’m hopeful it’ll happen this time. And maybe not just in Rwanda. Senegal, South Africa—there are places where this could get done.

Think Global Health: You helped establish the University of Global Health Equity in Kigali, Rwanda and recently broke ground for a Maternal Center for Excellence in Kono, Sierra Leone to educate the next generation of clinicians there. What do you forecast as their impact?

Paul Farmer: When I went to Rwanda in the early 2000s, there was only one medical school, and it graduated around 60 students a year. How can that small number serve 12 million people? That’s not possible. Even just starting a second medical school focused on bringing young women into the medical workforce, that would be good enough to justify it.

We started the University of Global Health Equity by training people in what we call global health delivery. So those folks were sometimes doctors, sometimes nurses, sometimes managers. We had done that for years in Rwanda, so by the time we launched the university, we had much greater ambitions: how can we serve the surrounding communities? How about Uganda, Kenya, Ethiopia, the Congo, Burundi, and Tanzania? So the idea was always to be a global university. And we’ve had American students take a master’s degree there or Canadians or people from the Middle East. But the idea was just to start with young Rwandans, mostly women—70 percent.

This year, for the medical school class, we are interviewing people from five or six countries. And I say “we” as if I’m doing the interviews. I’m not. They don’t trust me to do the interviews because I would admit everyone.

Think Global Health: What does it mean to focus on equity, in the curricular sense? Because you’re stating that as a very basic, fundamental principle. What does that mean and how does that change education?

Paul Farmer: If you look at the national AIDS plan of Rwanda, it’s very heavy on gender equity, social equity, food security, jobs, and focusing on what they call the bottom quintile. I never heard that in medical school.

I knew—we all knew—the poor, the marginalized, always bear the brunt. And not just of epidemic diseases but pretty much everything. So, to have the Rwandans focus on the bottom quintile—rural over urban, poorest over richest—explicitly, and weave that into their policies, was pretty amazing. They focus on the poor, on genocide survivors, widows, orphans, other marginalized people, and refugees.

These medical students at the University of Global Health Equity, even though they’re just starting their clinical rotations next year, they’ve already spent time in refugee camps, that’s part of their curriculum. Not just visiting, but actually working with refugees and those who help manage the camps. So, I’ve seen how it can work its way into the curriculum for every student as opposed to just those like me who self-identified as interested in these matters.

And I’m telling you, these kids—because they’re very young—will come out of their long medical training with a keen awareness of how social disparities influence not just the distribution of disease, but the therapy or preventatives that are required for it. So I’m really convinced that having this seep its way into every year, every rotation, is a big deal.

"A clinical desert is pretty scary, but there’s always a way to irrigate the desert"

Think Global Health: You’ve described the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) as perhaps the United States’ greatest global health achievement of the century. What should be the next PEPFAR? What should the United States be thinking about doing, aspirationally, on the global stage for public health?

Paul Farmer: The first thing that came to mind was COVID vaccines because it’s so obvious. The United States has a big role in addressing vaccine apartheid. But I was calling the White House today to nag and I realized after five minutes of speaking with a very highly placed official: they don't need my nagging. They just need help figuring out the cold chain, distribution, which vaccines. [Later that day, President Biden announced the United States would purchase and distribute 500 million doses to 100 countries over the next year]. So that’s a big deal—but let’s just say that is not the next great thing, because the United States should and could, and I believe will, do that.

The toughest part of the work of Partners In Health is getting people to invest in health system strengthening. That’s dull to talk about; who wants to hear about something that sounds so boring? We should call it “Beyonce” or something. It’s very important; it’s the basis of epidemic- or pandemic-preparedness, of responding not just with control but with care.

I believe the United States actually knows how to do it. And we can also prove that when you take care of people with AIDS, instead of dismissing them as not cost-effective, not feasible, not sustainable, but say that the standard of care should be the same in rural Haiti as at Harvard, then you open up this space to strengthen other vaccination programs, family planning, tuberculosis control, primary care, and health and wellness.

Of the 12 countries which I’ve gone to again and again or lived in for long periods of time like Peru, Haiti, Rwanda, Malawi, Lesotho—in each of those places, using those vertical programs to strengthen a basic health delivery system is the biggest thing the United States could do.

It’s been a while since I had been in such a desiccated clinical desert as Sierra Leone, or Liberia, for that matter. And you’re just reminded anew, as I was in Haiti in 1983 and Rwanda in 2000, that a clinical desert is pretty scary. But there’s always a way to irrigate the desert.

EDITOR’S NOTE: This interview was conducted via Zoom and has been edited for length and clarity. The article was updated on June 24, 2021 to include a map on TRIPS waivers.