Many observers have compared the health and economic damages caused by COVID-19 in the United States to the 1918-19 influenza pandemic and World War II. However, these comparisons fall short in demonstrating the significance of the pandemic. COVID-19 is the greatest public health threat the United States has ever faced. Against this pandemic backdrop, citizens, politicians, and legislatures across America have vilified public health officials, opposed public health measures, and weakened public health agencies. Such reactions to a killer pandemic imperil the ability of local, state, and federal governments to prepare for and manage future public health emergencies.

A Public Health Meltdown

The terrorist and anthrax attacks in September 2001 prompted national and state governments to enhance the authority and ability of public health agencies to respond to emergencies. Many state governments adopted all or part of the Model State Emergency Health Powers Act released in December 2001. These legal reforms dovetailed with efforts to strengthen public health and empower agencies to address emerging infectious diseases.

COVID-19 has proven to be a substantial threat to the United States. The country has experienced more than 81 million confirmed cases and nearly a million deaths tied directly to COVID-19. These staggering statistics represent approximately 15 percent of global cases and deaths—despite the United States accounting for only 4.25 percent of the world's population. During the pandemic, COVID-19 became the third leading cause of U.S. deaths after heart disease and cancers. COVID-19 has claimed more American lives in just over two years than annual influenza would claim in thirty typical seasons.

COVID-19 has claimed more American lives in just over two years than annual influenza would claim in thirty typical seasons

COVID-19 is not the only cause of pandemic-related mortality. U.S. deaths from opioids, alcohol, and vehicular collisions all spiked during the pandemic. Life expectancy among Americans fell from 78.9 years in 2019 to 76.6 years in 2021. Mental health disorders have also sky rocketed.

Such grim consequences did not arise from a "perfect storm" created by an unforeseeable convergence of unavoidable forces. Many other countries have controlled infections and limited deaths more effectively than the United States despite lacking comparable resources and health-system capacities. The pandemic has revealed domestic policy failures, public health weaknesses, and economic and social disparities. In such a powerful country claiming to be a global health leader, the pandemic has been nothing short of a public health meltdown necessitating comprehensive reforms.

Who's to Blame?

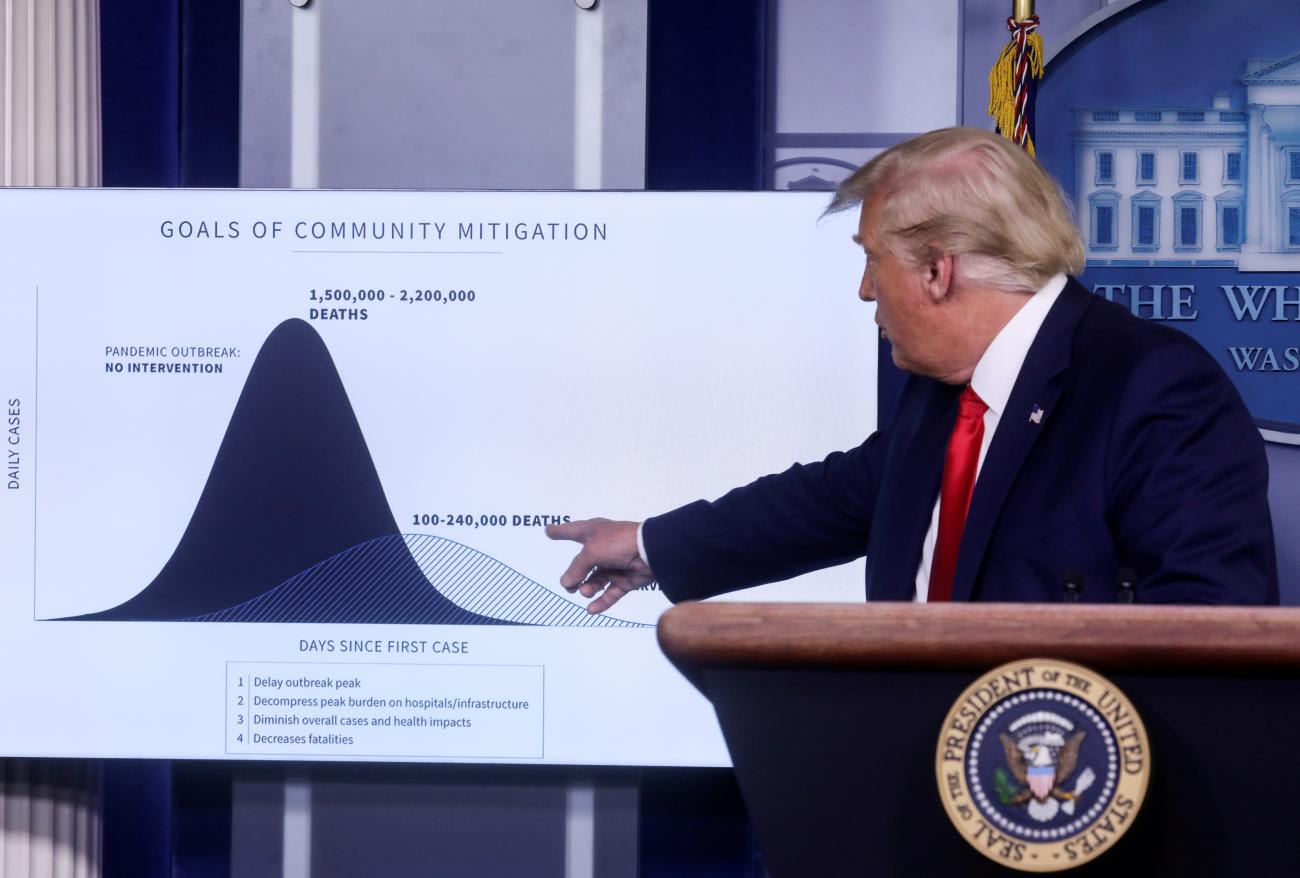

Slinging blame for the U.S. coronavirus catastrophe seems easy. Ineffective initial responses by the administration of President Donald J. Trump, coupled with a U.S. legal system that seemingly places most public health powers at the state level, contributed to failed approaches to control disease spread and obviate avoidable illnesses and deaths.

At subnational levels, however, early legal and policy responses looked promising. Every U.S. state, most U.S. territories, and countless local governments declared states of emergency by April 1, 2020—a first in U.S. history. Local, state, and territorial governments instituted an extensive series of social distancing measures, including business and school closures, travel restrictions, and stay-at-home orders.

Within mere weeks of their implementation, however, Americans began to contest such "draconian" interventions. Fueled by the anti-public health rhetoric of political leaders, Americans voiced their objections. Groups stormed capitol buildings in several states. Thousands of lawsuits challenged the exercise of public health emergency powers. Responses to COVID-19 were politicized as threats to the American way of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness rather than treated as measures to protect national security, the economy, and individual and community health.

Hundreds of thousands of Americans died during delta and omicron variant waves because they refused to practice social distancing or wear masks

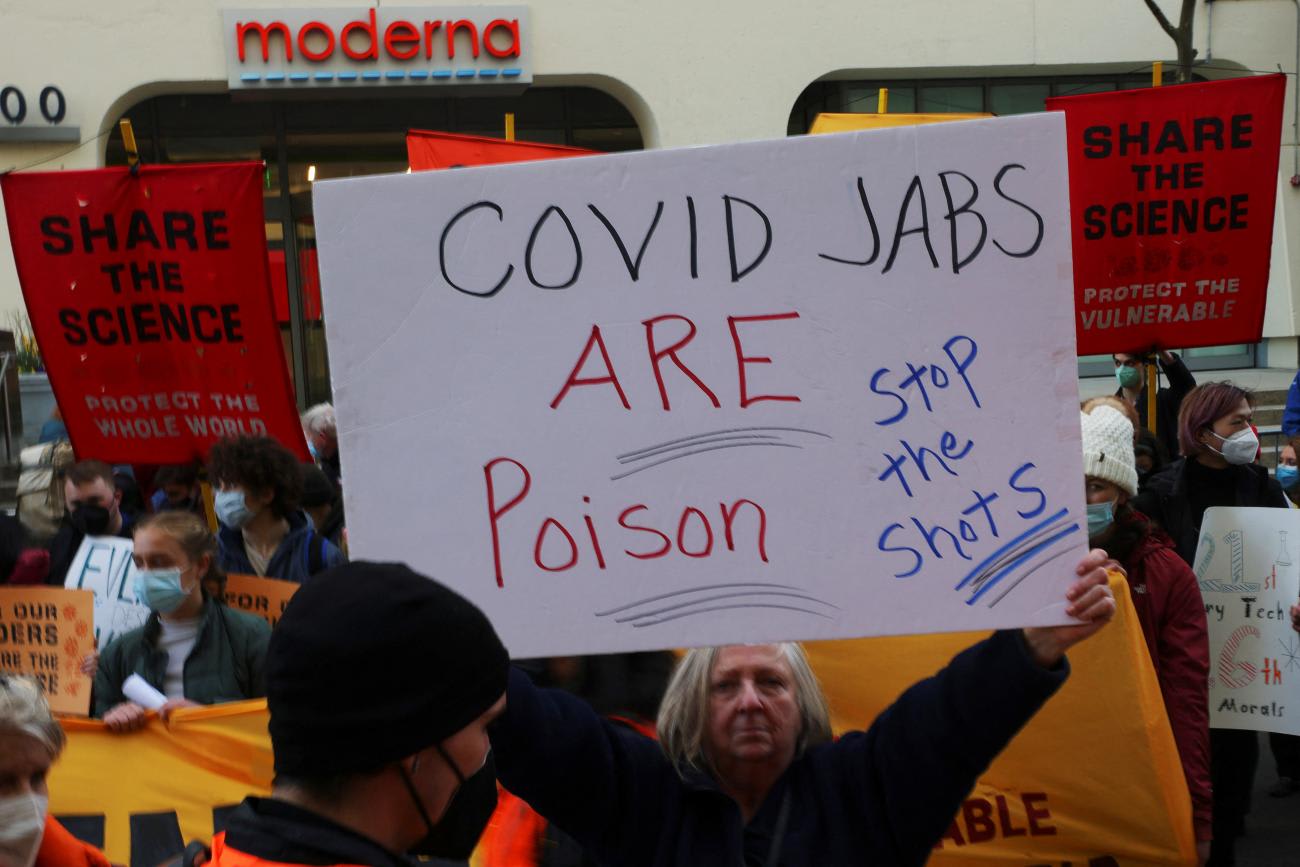

Consequently, multiple states dropped extensive social distancing measures too soon despite evidence of their effectiveness. Schools and businesses were re-opened without recommendations from epidemiologists. Travel restrictions were lifted. Masks were shunned. Even as effective vaccines became available, millions of Americans rejected them, politicians questioned their safety, and vaccine misinformation spread. Hundreds of thousands of Americans subsequently died during delta and omicron variant waves because they refused to practice social distancing, wear masks, or be vaccinated.

A Tsunami of "Denialism" Legislation

The divisive politics of the pandemic also produced a wave of "COVID denialism" in the United States. Politicians introduced thousands of bills in state legislatures to curtail the authority of public health agencies. Anti-public health proposals dominated legislative agendas and threatened to undermine governmental duties to protect and promote population health.

Central themes of state bills centered on:

- Limiting the duration of formally declared public health emergencies;

- Diminishing coextensive emergency powers of state and local health agencies;

- Controlling governors and public health agencies through excessive legislative oversight;

- Curtailing closures of businesses, schools, and especially religious entities;

- Inhibiting mask requirements in schools and businesses;

- Disavowing vaccine mandates or passports; and

- Subjecting perceived deprivations of individual liberties caused by public health measures to judicial "strict scrutiny," which few governmental actions survive.

Some of these themes resonated with the model Emergency Power Limitation Act that the conservative American Legislative Exchange Council issued in 2021.

In several jurisdictions, legislative proposals were tied to limiting executive public health powers. Legislators in Michigan introduced numerous bills to strip emergency powers from the governor and the state health department. Governor Gretchen Whitmer (D) vetoed several bills, but subsequent judicial challenges stripped her office of some emergency powers.

In Ohio, the legislature challenged gubernatorial powers through Senate Bill 22, which established a legislative health oversight committee, limited emergency declarations to ninty days, and empowered legislative rescissions of emergency actions by the executive branch. Governor Mike DeWine (R) vetoed the bill in March 2021, but the legislature quickly overrode his veto.

All Is Not Lost

The actions to limit state and local public health powers amid the worst communal health event in U.S. history are troubling. Politics in the United States have radically changed since the bipartisan efforts to strengthen public health during the first decade of this century. The pandemic has exposed a transformed political context rife with the rejection of science, distrust of government, proliferation of disinformation, and expansive claims of individual freedom. In this environment, limiting public health powers has become a potent rallying cry.

COVID-19 has illuminated the subjugation of state and local governments to federal authority during public health emergencies

Public health consequences may seem dire. Governors and public health agencies could be prevented from implementing effective interventions in the future. Local governments may be preempted from engaging in novel approaches. Preventable illness and death could worsen in future outbreaks because public health powers have been slashed by political actors hostile to the role of science and government's responsibility to protect the public's health.

Anti-public health, "denialist" approaches, however, could have limited effects. Most of these state legislative bills are either unenacted or vetoed. The potential impact of passed bills is also somewhat muted. Numerous enacted laws sunset when the COVID-19 pandemic ends. The language of some laws is so vague that it is unlikely to survive subsequent constitutional reviews in courts. Some laws focused on limiting a particular public health power (for example, emergency closures) fail to constrain use of different authorities—such as public health nuisance abatement—to achieve the same end. In some jurisdictions, the governor's intact powers to waive conflicting statutory provisions in declared emergencies can override the very legislation designed to inhibit such executive branch responses.

More importantly, many of these laws and legislative proposals are premised on state governments' control over responses in future public health emergencies. This may be a false conclusion. COVID-19 has illuminated the subjugation of state and local governments to federal authority during public health emergencies. Multiple state-based reforms are directly subject to federal preemption, overrides, lawsuits, or spending limitations.

For better or worse, the pandemic demonstrates how the federal government is increasingly "calling the shots" in public health emergencies that are characterized as threats to national security. In the future, state and local governments might exercise their public health powers under policies and rules they do not make or control.