During the COVID-19 pandemic, health measurement terms flooded Americans' vocabulary. Some of those phrases, like "hospital bed capacity," fed into to a collective anxiety about care for our sick friends and relatives. Others, such as the "reproductive number" (R) sounded like mathematical magic. But one term, "years of life lost" (YLLs), or the idea that "every death represents years of potential life lost, years that might otherwise have been filled with rich memories of family, friends, productivity, and joy," described the toll of the pandemic on people's lives. The concept of YLL was developed seventy-five years ago by Mary Dempsey, a U.S.-born researcher.

"Mary Dempsey was the first that we know of who came up with the idea of measuring loss of health in units of time," Christopher Murray, the director of the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation and a professor of global health, told me. The first time I heard Dempsey's name, I was listening to a recording of a discussion between Murray and Daniel Hausman, research professor in the Center for Population-Level Bioethics at Rutgers University. They were discussing health metrics, a field that uses data science to inform health-care policies and interventions.

How is it that someone who devised such a foundational measurement has remained in the shadows of history?

I wanted to learn more about this trailblazing scientist, but a quick Google search yielded scant information: at the time of writing, Wikipedia includes no articles about her and no biography pages are to be found readily elsewhere. Little documentation exists beyond a WorldCat page collating the articles and reports she wrote. I thought, "how is it that someone who devised such a foundational measurement has remained in the shadows of history?" Thus began my attempt to preserve Dempsey's life story and achievements.

Who Was Mary Dempsey?

Mary Veronica Dempsey was born to a prominent Catholic family in 1888. She graduated from Waterloo High School in 1904, in Waterloo, New York. After beginning her undergraduate studies at Syracuse University, she eventually left New York state entirely to finish her degree in 1912 at the George Washington University, in Washington, DC.

After graduating from college, Dempsey took a job as a special agent in the newly created Children's Bureau in the Department of Labor. At the Children's Bureau, she conducted a study on infant mortality, in Brockton, Massachusetts, a town known for its single industry: shoe manufacturing. Dempsey chose Brockton for three reasons: Massachusetts had excellent birth records, the shoe industry paid high wages that allowed for a high standard of living, and the town was known for its comparatively low infant mortality rates. Dempsey concluded that, despite those perceived advantages, "the infant mortality rate should have been lower than it really was." The reason, she explained, was a lack of nurses in the community to support the prenatal care of pregnant women.

After her stint with the Children's Bureau, Dempsey transferred to the Department of Labor's Women's Bureau, where she worked for the bureau's founding director, Mary Anderson. Dempsey produced her first major report for the department in 1922, The Occupational Progress of Women, which relied heavily on the U.S. Census of 1920. She wrote an updated version of the report in 1933, and both of these reports show Dempsey's commitment to thorough investigation, clarity of presentation through graphs and tables, and rigorous mathematical assessment. During this significant time of transition for women in the U.S. workforce, as women filled the roles vacated by men who left to fight in World War I, Dempsey's optimism for women's occupational future shone through in her reports. "It seems likely that the woman in business is here to stay," Dempsey wrote.

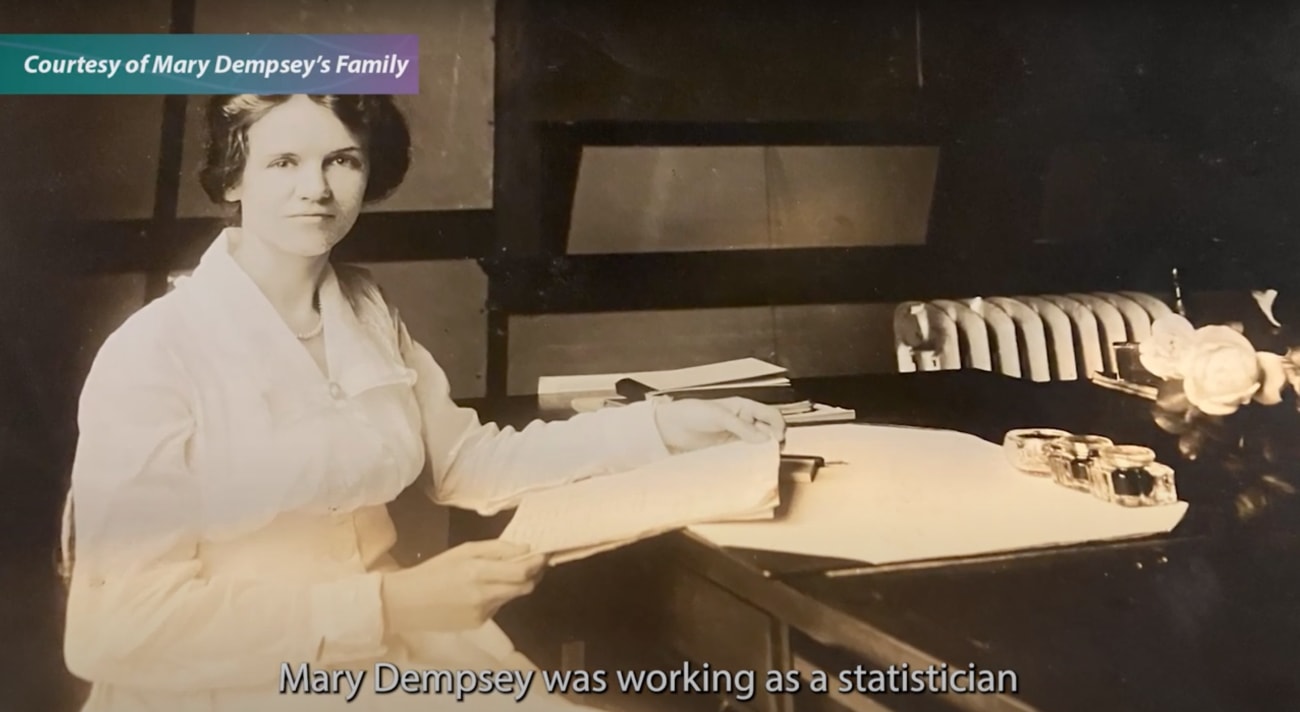

Between the 1930s and 1940s, Dempsey became a statistician for the National Tuberculosis Association (later renamed the American Lung Association.) During this period of her career, in 1947, Dempsey invented the concept of Years of Life Lost in her short article "Decline in Tuberculosis, The Death Rate Fails to Tell the Entire Story."

Changing the Health Metrics Landscape

In the "Decline in Tuberculosis," Dempsey showed that traditional measurements of mortality can be skewed toward diseases that most affect older people. But when years of life lost are accounted for, researchers are able to better understand which diseases — including tuberculosis — affect younger populations.

When Dempsey compared mortality rates among leading causes of natural death, heart disease presented itself as more than seven times more lethal than tuberculosis and cancer as more than three times more lethal. But when she presented years of life lost by these three causes, she found that heart disease remained a leading cause of death, but cancer and tuberculosis were much closer together in the "all group" category.

Potential years of life lost by cause in the United States in 1944

This new way of measuring health also helped researchers better understand health disparities in a population. When potential years of life lost are taken into account, it becomes clear that people of color are disproportionately affected by the disease. In fact, Dempsey showed that tuberculosis was the leading driver of loss of health among people of color in the United States at that time, referring to it as "the most serious public health problem." In conversation, Murray noted that "[Dempsey] is starting out a whole tradition . . . pointing out disparities, and saying that the metric you use changes how big those disparities [are]."

Dempsey's article, like the reports she wrote earlier in her career, was written to inform policymakers of not only the problem, but also where interventions are necessary. Dempsey made clear in "Decline in Tuberculosis" that success in the fight against the disease had been made, but that continued interventions were needed, especially for communities of color. Further, the tool that she designed, YLL, foreshadows the many other health measurement tools that were to follow. Policymakers and government agencies use YLLs regularly, along with other health measurements, to help inform interventions that lead to a healthier society.

In my conversations with Murray about Mary Dempsey, he reminded me why this project about Dempsey is worthwhile. "It's really important, from my point of view, to get intellectual history right," he said. "We should understand where our ideas come from and who played this critical role." I was also reminded that Dempsey is one of many woman researchers whose contributions have been overlooked. Dempsey's contribution to global health, and more broadly to the sciences, could have easily slipped by us. This article is just one attempt to bring to life a narrative that could have been left to the margins of history to live only in our bibliographies and footnotes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS: The author thanks Katherine Leach-Kemon and Annie Chan for their invaluable feedback, support, advice on charts, and edits; Tim Exton for bringing the story to life through video; Laurent Grosvenor for conducting a sensitivity reading; Rebecca Sirull for fact-checking the piece; and Professors Christopher Murray and Emmanuela Gakidou for their support of the project. The author would also like to thank Mary Patricia Fry, Richard Keller, and Jennifer Sheehy for sharing their family photos and documents.

EDITOR'S NOTE: The author is employed by the University of Washington's Department of Health Metrics Sciences and is a member of the Organizational Development and Training Team at the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). IHME collaborates with the Council on Foreign Relations on Think Global Health. All statements and views expressed in this article are solely those of the author and are not necessarily shared by their institution.