The COVID-19 pandemic has forced a reexamination of the global trade system. This scrutiny involves assessing what the pandemic revealed about the strengths and weaknesses of the system, including its ability to operate during worldwide health crises.

So far, the conversation among policymakers has prioritized how COVID-19 produced adverse commercial consequences by causing shortages of critical products and disrupting supply chains, transportation services, labor forces, and the flow of goods. These discussions acknowledge that the trade system needs improvement.

In this reevaluation, policymakers rarely question how international health law fits into the rule-based international trade regime. The pandemic demonstrates that commercial adjustments to a disease crisis do not lead to better trade or improved health outcomes. After COVID-19, it is not enough to assert, as some have, that "trade policy is health policy." Instead, now is the time to ask: Should the trade system more seriously embrace international health law?

Should the trade system more seriously embrace international health law?

A Primer on Trade and Health

The relationship between international trade law and health has a long, often contentious history. Trade rules demand that health measures, such as food safety regulations, not restrict trade without justification. Health advocates worry that these constraints unduly limit how governments protect health.

In balancing these interests, international trade law offers two principal solutions. The law recognizes a country's right to protect health but requires that health measures be based on science and not restrict trade more than is necessary to address risks. In addition, trade agreements include exceptions that allow a country to violate trade-liberalizing rules, such as the prohibition on export bans, when necessary to protect health.

Intellectual property (IP) rules in trade agreements also have a direct impact on health regulation. International trade law requires countries to protect IP, including patents. In the past, such obligations created health concerns because patent protection can limit access to drugs and vaccines. Here, too, trade law offers exceptions by recognizing a country's right to override patent protections through, for example, a compulsory license to increase access to a patented pharmaceutical, such as antiretrovirals for treating HIV/AIDS.

In both the general principles applicable to imports and exports and in the IP context, trade law exceptions accommodate urgent health-based regulatory moves by governments to get medicines, medical equipment, food, and vaccines to their people.

The COVID-19 Conundrum for Trade

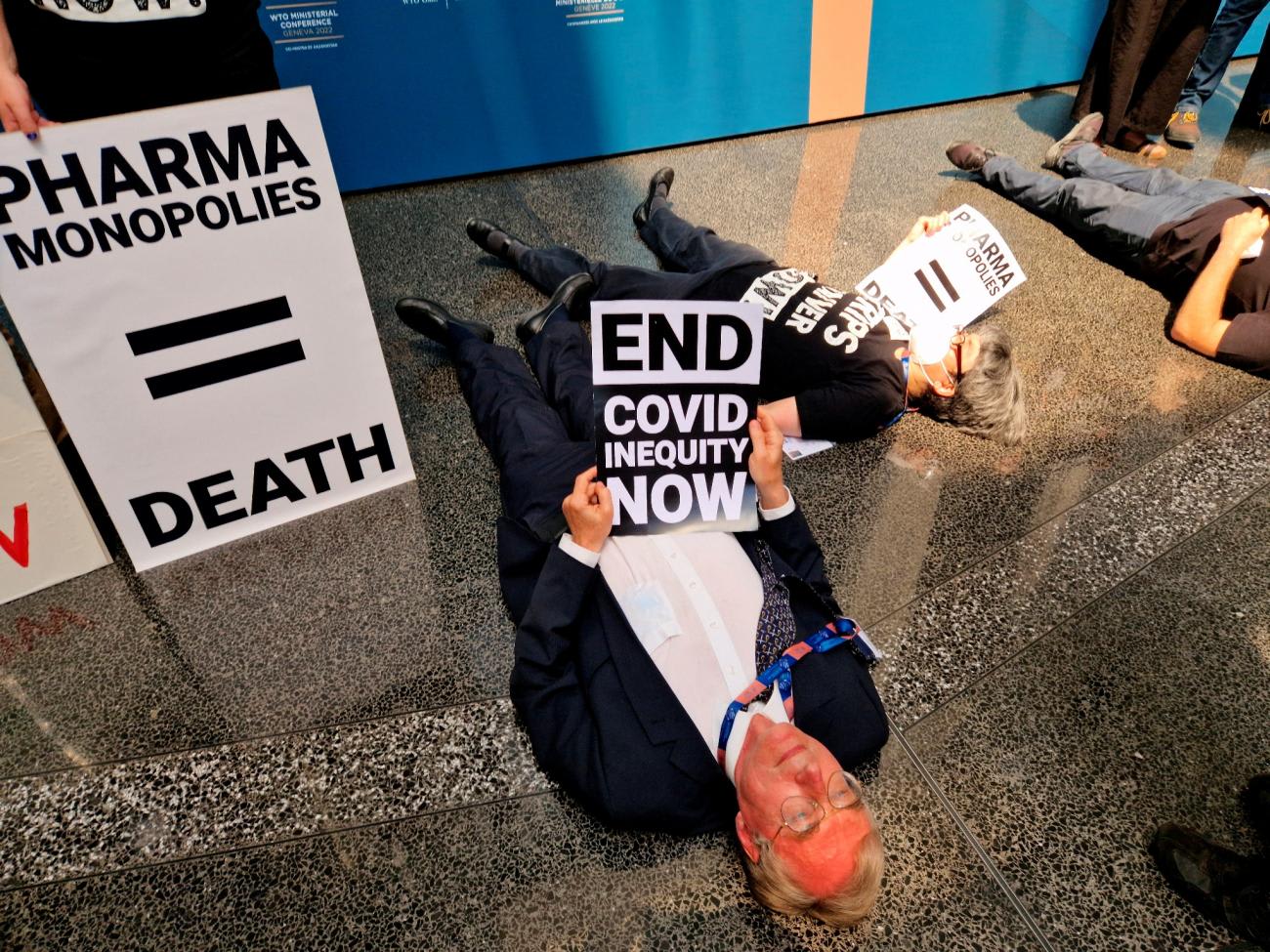

During COVID-19, many countries responded to the pandemic by deploying exactly the type of policies that the trade rules prohibit but for which the exceptions arguably were designed. For example, some governments restricted or banned the export of critical health goods. Inequitable global vaccine access also sparked IP controversies and a push within the World Trade Organization (WTO) for a waiver of IP protections for vaccines.

In both contexts, reliance on the trade system's exceptions proved suboptimal. Export restrictions harmed COVID-19 responses by other countries and international organizations. The WTO only reached agreement on an IP waiver after global vaccine scarcity was no longer a crisis.

In addition, the damage that COVID-19 inflicted has prompted many countries to consider improving national preparedness for pandemics by strengthening supply chains through onshoring, near-shoring, or friend-shoring manufacturing and distribution capabilities. This trend is likely to continue, and it creates a conundrum for the trade system: How do states maintain an international rules-based system designed to liberalize trade while building national capacities that support greater domestic crisis preparedness and response?

Answering this question is difficult. For many policymakers, COVID-19 underscored the need to create resilience and eliminate vulnerabilities at home, including those created by trade-restrictive measures that other states take. Being more health-protective frequently involves more protectionist approaches. By contrast, trade liberalization advocates want more free trade with tweaks to exceptions to address crisis exigencies, such as vaccine manufacturing and distribution. In sum, the foundational principles of free trade and the political demands of crisis preparedness do not easily align, and the trade system's regime of exceptions cannot resolve this problem.

If the trade system better reflected international health law, countries could better prepare for, and mitigate, the next shock

Another Way to Align Trade and Health

In the wake of COVID-19, a different approach would involve integrating express international health law commitments into the trade system. The exceptions regime allows governments to breach the rules, but the exceptions do not guide governments in preparing for and responding to pandemic or other systemic shocks. Similarly, IP rules do not direct governments on strengthening health resilience. If the trade system better reflected international health law, countries might be more prepared for, and able to mitigate, the adverse consequences of the next shock.

Trade law already contains precedents for such an approach. Since the Cold War ended, the system has expanded into areas once outside the trade sphere. For example, bilateral and regional trade agreements often contain rules designed to protect labor and the environment. These provisions require the parties to adopt and implement regulations consistent with internationally recognized labor and environmental obligations. Some trade agreements directly incorporate obligations found in multilateral labor and environmental conventions.

Putting these obligations in trade agreements has a further benefit that these areas of international law lack—binding dispute settlement with penalties for countries that do not comply. Such positive and enforceable commitments go beyond the maintenance of exceptions for regulatory actions that uphold labor rights and environmental protections. They set standards and guide governments to achieve a threshold level of policymaking.

Should the trade system follow this path with international health law?

The most relevant health treaty is the International Health Regulations (IHR) adopted by member states of the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2005 to address disease events that might constitute public health emergencies of international concern. The IHR share trade law's normative orientation toward minimizing burdens on international commerce. The similar logic of these regimes makes it likely that parties to economic disputes will refer to the IHR, opening the door to trade litigators pronouncing on their scope and interpretation.

But rather than ask trade law experts to discern the contours of a health-based exception, a task for which they likely lack the expertise or mandate, governments could take more meaningful steps toward prioritizing positive health commitments. Integrating IHR obligations, such as on disease surveillance and maintaining certain national public health capabilities, into trade agreements could be a first step. The pandemic offers an opportunity to imagine what trade institutions would look like if driven at least in part by health-law values.

More broadly, COVID-19 demonstrated that pre-pandemic global health governance was likewise inadequate for handling such dangerous disease events. The IHR have no provisions on supply chains, IP rights, or sharing pharmaceuticals and other health goods during outbreaks. In response, WHO member states recently agreed to revise the IHR and negotiate a treaty to strengthen national and international pandemic preparedness and response.

Whether the revised IHR and the pandemic treaty will have provisions that the trade system could constructively incorporate remains to be seen, but those conversations could and should begin now. Otherwise, health exceptions will continue to reinforce the view that health and trade rules are insufficiently flexible to allow states to confront these problems effectively.

Cross-fertilization between international law on trade and health requires governments and international organizations to take up this project whenever and wherever possible. Multilateralism is important in building norms, but, as happened with international labor and environmental law, bilateral and regional trade agreements might be best suited for exploring and experimenting with how to address the trade-health issues that COVID-19 generated.

A New Trade and Health Moment

COVID-19 has opened the door to a possible realignment of trade law and health interests. For the trade system, this moment offers the possibility for new forms of economic governance and careful integration of more issues into international trade law. Policymakers should take this opportunity to protect health and trade more effectively given the likelihood of future pandemics and other health shocks.