When I started my medical and public health career twenty years ago, I was working to fight the HIV epidemic in countries such as Lesotho, Rwanda, and Uganda, where an AIDS diagnosis was a death sentence. The virus devastated communities, economies, and entire countries. At one point, in African nations such as Eswatini and Lesotho, upward of 30 percent of the population was infected with HIV, and AIDS deaths left a generation of orphaned children. Although treatment was available in the industrialized world, it was mostly out of reach, unaffordable, and inaccessible for the countries and the people we were trying to save.

At one point, in some African countries, upward of 30 percent of the population was infected with HIV

One of my first field jobs involved supporting antiretroviral (ARV) treatment programs in southwest Uganda, one of the first places in the developing world to introduce ARVs outside hospital or advanced health-care settings. I drove around day after day, clinic to clinic, working directly with nurses, often in single-room clinics with few medications and support, relying on paper records. Many had unstable supplies of electricity and water.

The infusion of support, improved recordkeeping, and—most important—life-saving drugs for HIV, not only pushed care at these clinics forward but also transformed patients' lives and improved morale for these frontline health-care workers who finally saw the impact of their hard work, despite the difficult environment.

I saw later, in places such as Lesotho and Rwanda, how massive support and public-private partnerships for HIV could have ripple effects on entire health systems, including improved health-care infrastructure, data and communication systems, workforce training, all while saving countless lives in the process. It was a transformative experience to witness the impact, both individual and systemic, when governments and communities are ambitious and come together around shared values of equity and fairness—and shared public health goals—to tackle a pandemic.

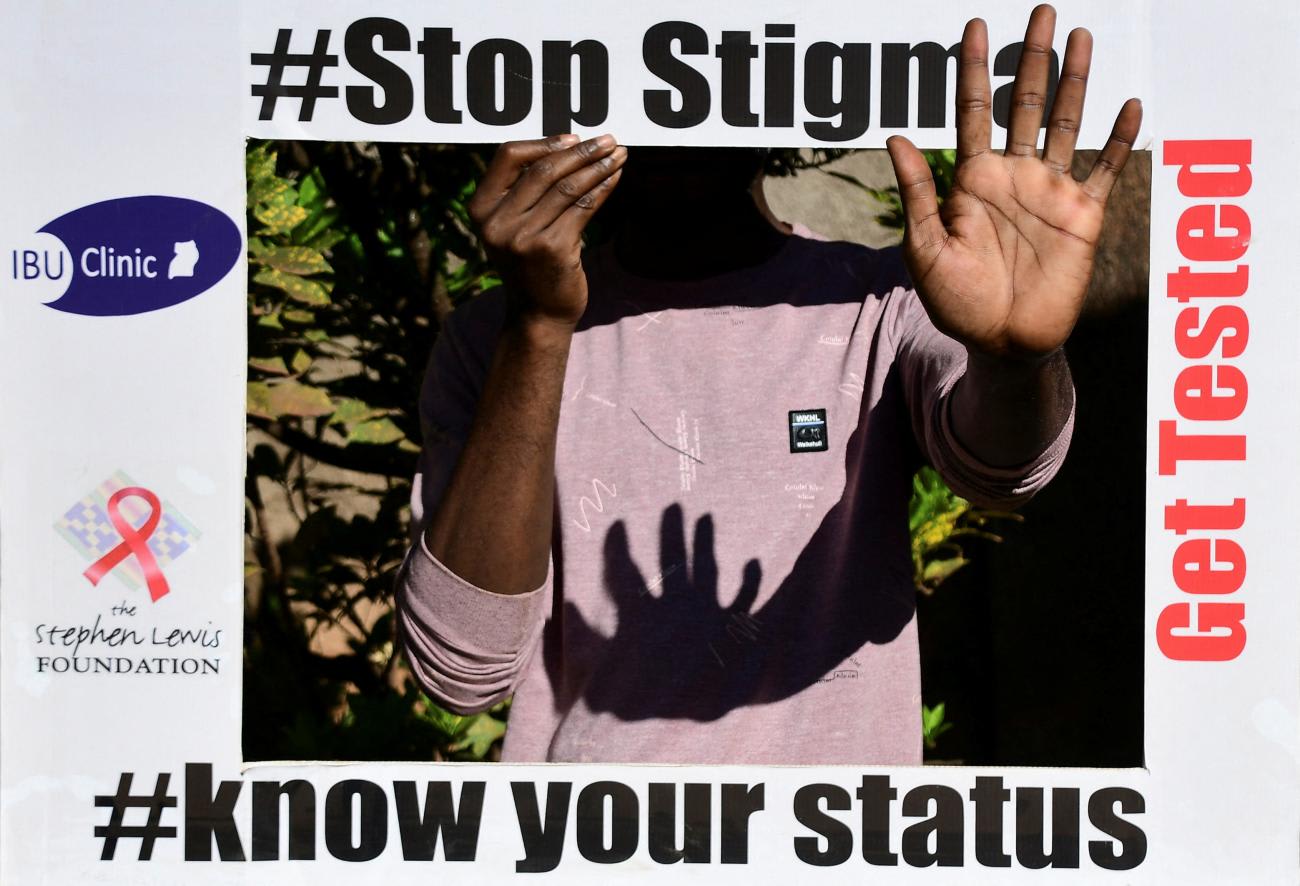

Incredibly, today, and in no small part due to this concerted global effort to fight HIV, five countries in Africa have eliminated the disease and another sixteen are close to hitting the United Nations' Sustainable Development Goals' 95/95/95 target of having 95 percent of people know their status, 95 percent of HIV-positive people receive ARVs, and 95 percent of people on ARVs have viral suppression.

President Biden recently said, "We are within striking distance of eliminating HIV-transmission." A remarkable statement, and a realistic one. One that I would never have imagined twenty years ago when I started my journey in public health.

This progress is largely thanks to the U.S. President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, or PEPFAR, a program started by President George W. Bush with ironclad bipartisan support twenty years ago, which distributed life-saving ARVs and ensured that the most vulnerable people in the world had access. PEPFAR represented the best of American leadership on the global stage, galvanizing unprecedented support from the American people as a part of the global community, to fight a common scourge on the frontlines.

It reminded us of where the United States and the Global North were just ten years earlier in the 1990s, when hospitals were filled with young people dying from AIDS and before ARVs were available. U.S. elected leaders demonstrated through PEPFAR that they knew the United States was not isolated and that the nation's ability to address global challenges has impacts here at home.

In New York City, cases have fallen by 72 percent since 2001

PEPFAR coincided with massive gains in our fight against HIV domestically. The United States poured resources into a range of proven interventions from testing and outreach to treatment, and this helped us drive down the number of new infections. In New York City, where I serve as health commissioner, cases have fallen by 72 percent since 2001.

But concerning news has emerged showing that the reauthorization of PEPFAR is at an impasse in Washington.

First PEPFAR, then Domestic Public Health?

Since it began in 2003, PEPFAR has saved an estimated twenty-five million lives around the world, making it the most pro-life U.S. health policy abroad.

Significantly, the program has provided treatment for millions of orphans suffering from HIV. It has also protected more than five million children from contracting the disease in the first place by providing 82 percent of HIV-positive pregnant and breastfeeding women with ARVs.

PEPFAR, in other words, has helped get the world to the precipice of turning AIDS into a painful memory in some places and a rarer disease that can be effectively treated and controlled in others. Unfortunately, it has come under partisan attack from some in Congress who object to the program's funding of AIDS and HIV treatment organizations that also provide reproductive health care.

Without a fully funded PEPFAR, the globe would not just see progress stall. It would see instead an increase in infections and, ultimately, deaths, at the very moment when the end is in sight.

Threatening PEPFAR is part of a broader environment where HIV and sexual health care are being undermined here at home. More than $400 million in cuts to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to fund frontline disease detectives and outreach workers is making it harder to address sexually transmitted infections (STIs), HIV, and other communicable diseases here and abroad. Taken together, we are seeing major gaps emerge in a system that was helping our country and our world fight AIDS, treat other related diseases, and prevent epidemics.

This trend is having local consequences. Here in New York City, CDC cuts included in the Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023 have resulted in the city's health department losing more than $16 million for sexual health services, leaving us unable to provide essential care for sexually transmitted infections and support to more than 2,500 New Yorkers a year. This is happening in the midst of STI increases in New York City and nationwide despite knowledge that rising rates of STIs also increase the risk of HIV transmission. This retreat on PEPFAR and on sexual health care here at home is the wrong approach at an especially wrong time.

Also, because PEPFAR has helped build health infrastructure where it did not exist, the world has been better prepared for health threats such as COVID-19, SARS, and Ebola. Scaling it back would mean rolling back those gains, being less prepared for global health emergencies, and needlessly losing lives to known and unknown infectious diseases worldwide.

This retreat on PEPFAR and on sexual health care here at home is the wrong approach at an especially wrong time

In a matter of decades, AIDS has gone from being a death sentence to a treatable and often preventable disease. It is the kind of miracle public health professionals dream of. But rather than fighting to finish the job, we are on the verge of throwing away our progress because some pro-life politicians refuse to prioritize life over politics. It is hard to think of a policy less pro-life than defunding PEPFAR, as former President George W. Bush said.

In today's hyperpartisan world, and entering an election year when, despite increasing trends of insularity and nationalism, foreign policy remains a major issue for voters, Americans should remember recent history on HIV. It is a much-needed story of people coming together to end a deadly disease, the last great global pandemic before COVID-19. Because of this global movement, and because of leadership from the United States, we have saved millions of lives, and eliminating AIDS—once an unimaginably optimistic goal—is truly within reach. But legislators need to help.

Congress has an opportunity to come together again to end AIDS once and for all, and it can do this by reauthorizing a fully funded PEPFAR. Nothing would be more pro-life—particularly at a time when the end of this scourge is so close.