At September's UN General Assembly (UNGA), Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and Syrian Interim President Ahmed al-Sharaa met to discuss implementing the March 10 agreement.

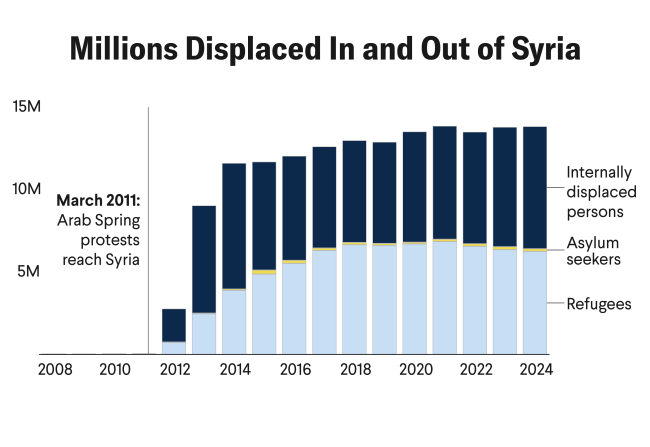

Signed by al-Sharaa and Syrian Democratic Forces Commander Mazloum Abdi, the agreement could shape the nation's efforts to rebuild after more than a decade of war, displacement, and political division. The agreement contains eight points that include guaranteeing the rights of all Syrians regardless of their ethnicity to representation and participation, rejecting calls for division and hate speech, and calling for a ceasefire on all Syrian territories.

Notably missing from its text, however, is any reference to health care despite caretaker government claims to prioritize health-care stabilization, and the UNGA negotiations did not include Kurdish representatives. At a moment when Syria's health system lies in ruins and minority regions face particularly acute shortages of medical staff and supplies, these omissions reveal a critical divide between political symbolism and the practical needs of postconflict recovery.

Kurdish people could play an indispensable role in successful postconflict recovery

In northeastern Syria, Kurdish Rojava's health system—which was largely rebuilt during the war—could serve as model of success. Its decentralized, community-based programs are often led by women and feature co-chair system councils. Although Rojava's health system is a bright spot in Syria, integrating it into the new government without legal protections for health care could risk reversing hard-won gains in maternal health, epidemic response, and trauma care.

Kurdish people could play an indispensable role in successful postconflict recovery. Unless their governance structures, people-oriented health systems, and war roles are recognized by the new government, any process of recovery will be incomplete and transitory.

Responses to a Fragile Situation

In Rojava, the collapse of state health services was met with determined local action. Years of war, embargos on medicine, fuel, and humanitarian aid by Turkey, the Syrian government and restrictions from the Kurdish authorities in Iraq, and targeted attacks hollowed out the system—destroying hospitals, fracturing supply chains, and triggering a mass exodus of doctors and nurses.

Communities built parallel structures to continue delivering care. One of the most visible examples is the network of Ari Clinics, run by the women's organization Weqfa Jina Azad a Sûrî (WJAS). Operating in five locations, these clinics provide low-cost primary care for women and children who cannot afford private treatment. In Heseke, staff treat around 500 patients a month for conditions such as diarrheal disease, leishmaniasis, and chronic malnutrition.

Most medicines and medical supplies are purchased through donations from aid organizations and partnerships with local and international humanitarian organizations, the supplies often sourced from neighboring countries such as Turkey and Iraq before being transported to the clinics. Medicines are dispensed free of charge, and services include gynecology, pediatrics, and psychosocial support.

A small naturopathy center within the clinic produces herbal remedies for chronic illnesses, preserving local knowledge while filling pharmaceutical gaps. Now, following the overthrow of Bashar al-Assad's regime, this network faces growing risks because of the new government's political and ideological hostility toward autonomous and women-led initiatives. The changeover has led to threats of funding cuts and services in gynecology, psychosocial care, and community health as well as to tighter control or outright closure. Despite these pressures, the organization gets medicines from local producers, small deliveries from across the border, and donations from aid groups and private supporters.

In the rural area southwest of Kobane, Rojava, health-care services are expanding under projects such as the new Qena health center, which is set to serve 50 surrounding villages with free primary and maternity care. The expansion is mostly funded by local communes, international solidarity networks, and Kurdish diaspora organizations, but receives some support from humanitarian NGOs working there. Based on local council data and NGO assessments, these facilities are often the sole point of health-care access for tens of thousands of people. Any disruption could mean a complete collapse of care for the local population.

In Raqqa in April, a first-ever burn treatment operating room opened at the national hospital. This specialized facility addresses severe burn injuries, marking a significant step toward restoring surgical care capacity in the region.

Farther west, in Al-Tabqa, the Youth and Sports Authority is building an inclusive and broad understanding of health across all age groups by organizing lectures and seminars on mental health. This effort is also raising awareness about the growing risks of suicide among youth, focusing on the challenges facing the younger generation. Yet, under the new government, such programs are at risk of defunding or suppression, as their inclusive approach to mental health conflicts with the regime's political and ideological priorities.

International solidarity, though limited, has had an impact. A partnership between the Kurdish Doctors' Association in Germany and a hospital in Dêrik has delivered new dialysis machines and medical supplies; meanwhile, civic groups support water and education projects.

In fragile situations, however, those partnerships are at risk of being dismantled by new violence and a more fragile situation for volunteers: Because crossings to Turkey are limited, the Semalka border remains crucial but has often been shut down in times of conflict or political dispute. International solidarity and political pressure could play a decisive role in reopening border crossings by pushing both local authorities and regional powers to guarantee humanitarian access.

Separately, the absence of reliable data on water services reflects the same structural weaknesses that have crippled medical systems, leaving communities vulnerable to waterborne diseases such as cholera. In late 2024, after a series of Turkish military operations and blockades targeting water infrastructure, further restricted access to clean water, cholera cases surged, more than 1,400 suspected infections being reported within months. Poor data and fragile infrastructure have made tackling these outbreaks a challenge. The World Health Organization quickly launched an emergency response to stop the spread, focusing on clean water, sanitation, and hygiene. Unless the government prioritizes health care, these outbreaks could continue.

Syrian Minorities on the Brink

For minority communities including the Alawites and Druze, the caretaker government's reluctance to renounce its authoritarian, Islamist agenda [PDF] coupled with the health care's omission from the March 10 agreement, is cause for concern. In March, fighters linked to the Syrian National Army and Hay'at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS)—a militant group that split from al-Queda—and tribal forces are reported to have killed more than 1,500 Alawites, most of them civilians. These killings create a climate of fear and insecurity, adding fatal consequences for mental health to the physical harm caused by injuries and deaths.

The government's Islamist agenda is also visible in new education and social policies. Curriculum reforms have removed references to ancient gods, national symbols, and secular subjects, replacing them with stronger Islamic content and religious terminology such as substituting law of justice with Allah's law. At the same time, new dress code rules have imposed stricter modesty standards, including calls for women to wear burkinis on public beaches.

In July, a brutal wave of violence erupted in Sweida, a predominantly Druze region in southern Syria. The attacks claimed the lives of hundreds of Druze civilians. Hospitals, already operating under strain, received patients who were reportedly shot in their beds. Wards became overwhelmed, and medical staff were pushed to their limits. Testimonies reveal that hospital staff were forced to kneel at gunpoint, were interrogated, and had their faces photographed by militia members. Bodies were left to decompose in hospital corridors, and the stench of death clung to the compound for days. For many in Sweida, the hospital, once a symbol of care, became a site of terror, marking the collapse of even the most basic protections under international humanitarian law.

The situation in Kurdish Rojava is equally tense. Threatening gestures from the Turkish side and minor skirmishes at the Tishrin Dam, as well as in predominantly Arab-dominated areas such as Deir ez-Zor, are creating an unpredictable climate and renewing fears conflict and displacement. Communities already weakened by years of violence now face the prospect of once again losing their homes, security, and access to essential services.

Although implementation of the March 10 agreement is imminent, recent violence in Kurdish neighborhoods such as Sheikh Maqsud and Ashrafiya in Aleppo has further deepened mistrust, showing that genuine inclusion and protection for these areas have yet to materialize. Without explicit protections from central authorities and external political pressure, health professionals fear a repeat of these events.