In the first few months of the global response to the COVID pandemic, policymakers and health experts feared a coming surge of opioid overdose deaths around the world, driven by lockdowns, social distancing mandates, and the closure of addiction treatment services and care. Such public health protection measures, it was believed, might be isolating and lead to riskier substance use behaviors, such as accessing drugs from less trustworthy sources, or mismanagement of drug intake in the face of inconsistent supply.

How accurate were the predictions? Many countries were spared spikes in overdose deaths. But in the United States and Canada, the synthetic opioid fentanyl and lockdowns were a deadly combination.

The synthetic opioid fentanyl and lockdowns were a deadly combination

Preliminary data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) suggests that there was a pandemic-led opioid overdose surge in the United States. Overdose deaths from all drugs—not just opioids—spiked sharply upwards immediately following lockdowns in the United States in March of 2020.

United States Opioid Mortality

Understanding how much of an impact COVID lockdowns had on the opioid overdose surge in America is difficult, though. Pre-pandemic, many addiction experts and epidemiologists were already predicting a surge for years; in many states, the rate of opioid overdose deaths had already been accelerating before lockdowns even began. Experts had warned that the increasing availability and low cost of fentanyl, which is much more potent than heroin [2mg, the size of a tiny water drop, can be fatal], would lead to skyrocketing opioid deaths. From 2013 to 2016, the rate of deaths due to fentanyl increased fivefold as its use spread across the country, while the rate of deaths due to heroin tripled over the same period.

Even before the pandemic, there was strong evidence that fentanyl had increasingly contaminated other drugs. In 2019, 76 percent of cocaine deaths and 54 percent of psychostimulant deaths involved opioids, suggesting fentanyl was involved.

In 2019, 76 percent of cocaine deaths and 54 percent of psychostimulant deaths involved opioids

Dual crises make it difficult to know where to place blame. Varied trends in opioid deaths across states paint a complex picture—patterns that COVID-19 alone cannot explain. Analysis conducted at the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, an independent global health research center at the University of Washington, shows that many states experienced a constant pattern or continuing trend that began well before the virus landed in the United States.

In California, where the CDC only provides data since mid-2019, opioid mortality was increasing before the pandemic. The same was true in New York, where deaths began to tick up slowly in January 2020. In Massachusetts, overdose deaths have remained relatively unchanged since 2018.

In contrast, there are states where overdoses surged after lockdowns began. In West Virginia, one of the states with the highest rate of opioid mortality, monthly overdose deaths nearly doubled in the months immediately following lockdowns in March 2020 before tapering off again in June 2020.

Different Trends due to COVID by State

The inconsistent trends state-to-state suggest that an overall increase in opioid deaths nationwide after March 2020 is not necessarily due to the pandemic response. Most likely, a combination of factors contributed: increasing fentanyl availability, the contamination of other drugs with fentanyl and pandemic measures.

There is no clear explanation for some differences between states. For example, overall overdose deaths in Rhode Island increased by 25 percent from 2019 to 2020, yet neighboring Massachusetts, with similar pandemic responses and socioeconomic characteristics, saw only a 5 percent increase in deaths.

A similar story follows in Canada, where nationally, there was an increase in opioid overdoses after the start of the pandemic response in March 2020.

Opioid Overdose Deaths in Canada

Yet, when we break look at regions within Canada, we see stark differences. Alberta and British Columbia see a jump during the pandemic response, like West Virginia and Kentucky in the United States. These are two of the most populous regions, so they contribute far more to the total overall national opioid overdoses. The rest of the country looks very different. In Quebec and Ontario, overdoses were on the rise pre-pandemic, while the rest of the Canadian states saw no change in overdose patterns during the pandemic.

In provinces where overdose deaths spiked seemingly as a result of the pandemic, fentanyl use was increasing. The percent of deaths linked to fentanyl in British Columbia increased from 4.4 percent in 2012 to 62 percent in 2016. In Ontario, that proportion increased from 24 percent to 41 percent over the same period. In all other regions, the fentanyl proportion of all opioid deaths remains below 15 percent.

Opioid Overdose Deaths in Canada by Province

What About the Rest of the World?

Currently, the best source of information on opioids and other substance use disorders outside of North America is the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. Their COVID-19 trendspotter report—similar to the preliminary data from the United States—presents early data of opioid overdose trends in Europe and the impacts of the pandemic.

While final data on overdose deaths in Europe is not yet available, early hospital data show a decrease or flat trend in drug-related emergency admissions in some European countries. Daily emergency admissions in a hospital in Mallorca, for example, decreased by 50 percent during the first three months of the pandemic. In Norway and Ukraine, early mortality data show little change in mortality among opioid users during the lockdown period. This may be due in part to policies that were introduced or enhanced specifically to help the opioid-using population.

Daily emergency admissions in a hospital in Mallorca decreased 50 percent during the first three months of the pandemic

Methadone, an opioid agonist treatment, is often restricted to usage under a physician and requires an in-person interview to access. Policy changes were intended to reduce the friction and contact required in these cases by loosening restrictions on take-home doses of agonist treatments, greater use of telehealth, and a more proactive approach to clients with mobility issues by working with community-based services to connect with those in-need.

In the Czech Republic, Germany, Ireland, France, Italy, and Luxembourg, demand for substitution treatment—the use of drugs such as methadone and buprenorphine to help people withdraw from opioids— increased during the pandemic. Researchers suggest that supply chain issues made it harder for people in Europe to access their usual illegal drug supplies. At the same time, these governments loosened restrictions on treatment. These two factors may have contributed to more people seeking out treatment. In Ukraine, the Ministry of Health's strong policy response and quick transition to take-home doses of opioid agonist therapies may also have been a key factor.

Countries in Asia may have difficulty in ascertaining the true impact of the pandemic on opioid overdoses or any other substances due to a lack of data. The same is true for many regions of Sub-Saharan Africa and in North Africa and the Middle East, where data sparsity has long been an issue

Fentanyl is a Growing Global Threat

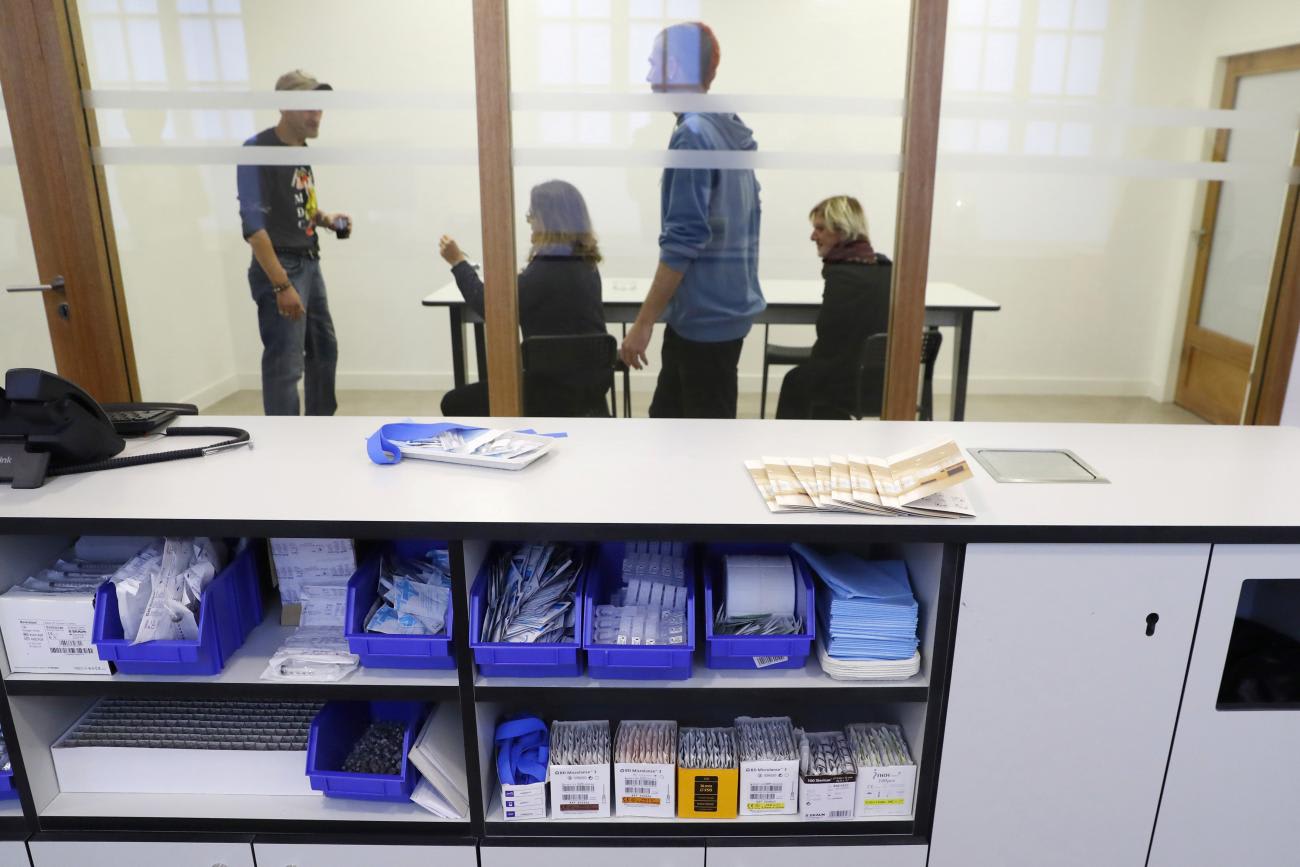

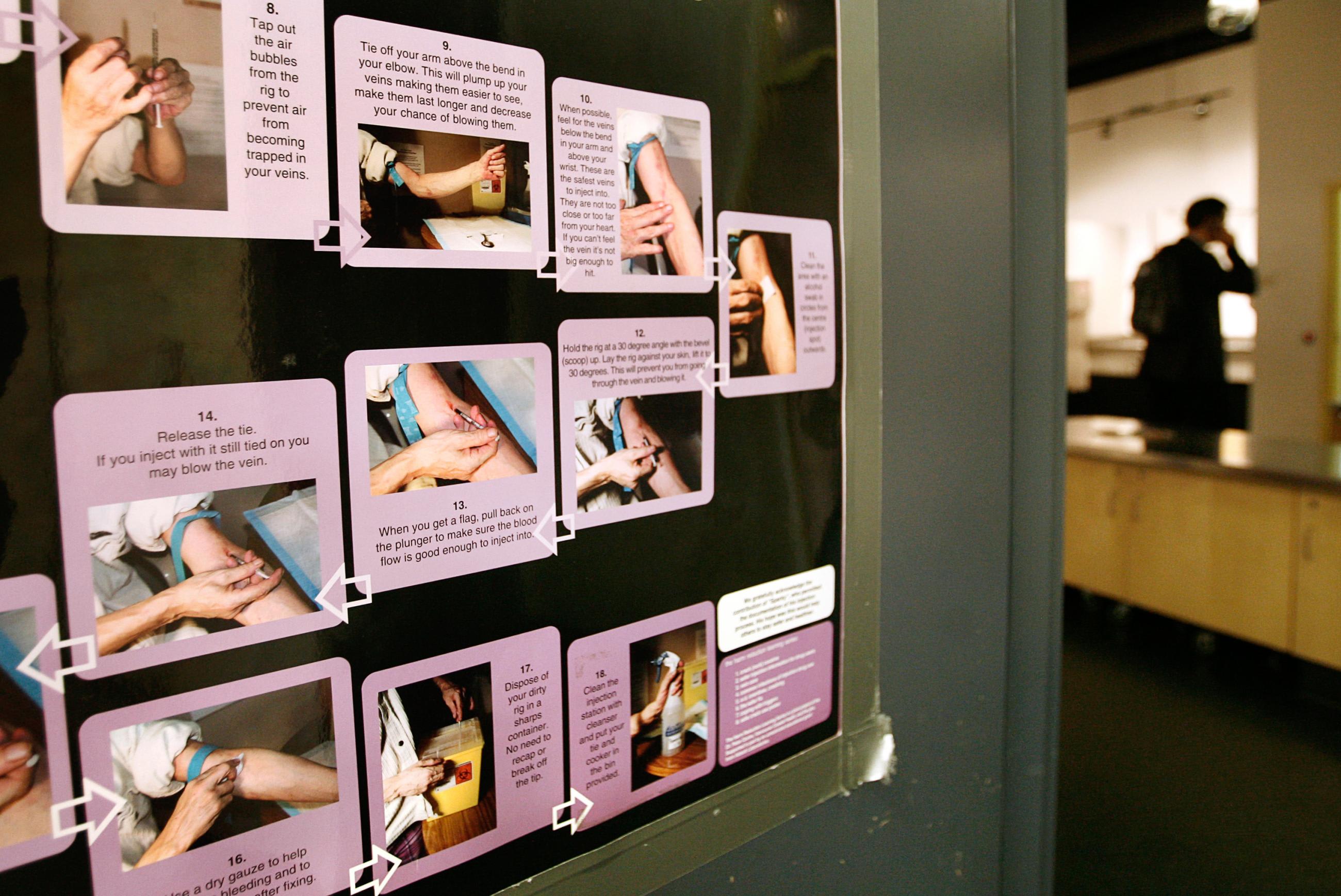

Although there was early concern that the pandemic would increase opioid and fentanyl use and reduce access to treatment, increases in deaths were not seen in many locations around the globe. To help untangle the roles of fentanyl supply, policy changes in countries, and reporting challenges in many nations, it is crucial to better monitor fentanyl use and better understand its role in driving up opioid deaths. Fentanyl is here to stay, and countries such as the United States and Canada need to address the issue by implementing bolder policies, such as safe drug consumption sites or drug content testing. At the very least, funding for improved data infrastructure around drugs would improve surveillance of the continued spread before a surge in overdose deaths occurs.

The rest of the world should be concerned with the trends observed in North America. At the moment, Europe is still a small market for fentanyl compared to the United States, with only 0.4 percent of opioid users entering treatment and listing fentanyl as the primary type of opioid they use. Australia, however, may be the country of the most concern due to its large population of heroin users. If its main heroin supplier, Myanmar, reduces its output, a transition to greater use of fentanyl or more fentanyl-laced drugs is a grave possibility. There is a real threat that fentanyl will enter the supply of heroin in Australia and spread quickly before a policy response can be enacted.

Increases in deaths were not seen in many locations around the globe

While most of the world has escaped a huge spike in opioid overdose deaths in 2020, there are lessons to be learned. In assessing the trajectory of opioid mortality, the biggest concern is that policymakers will blame the increase in opioid overdose deaths on the pandemic, but as noted, the surge was well underway before COVID-19 emerged. People with opioid use disorder—or any substance use disorder—will continue to need treatment.

The COVID-19 pandemic has revealed the dangers of indecision when public health decisions are required. The early opioid death data out of Canada and the United States should push policymakers around the world to act quickly to prevent the spread of fentanyl use in their own countries in order to save lives.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: The author would like to thank Dr. Liane Ong and Tim Exton for their feedback on this post, and Professors Christopher Murray, Stephen Lim, and Theo Vos for providing input on the analysis. The author would also like to thank Professor Brandon Marshall at Brown University for his thoughts on the opioid and COVID-19 situation.

EDITOR'S NOTE: The author is employed by the University of Washington's Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). IHME collaborates with the Council on Foreign Relations on Think Global Health. All statements and views expressed in this article are solely those of the individual author and are not necessarily shared by their institution.