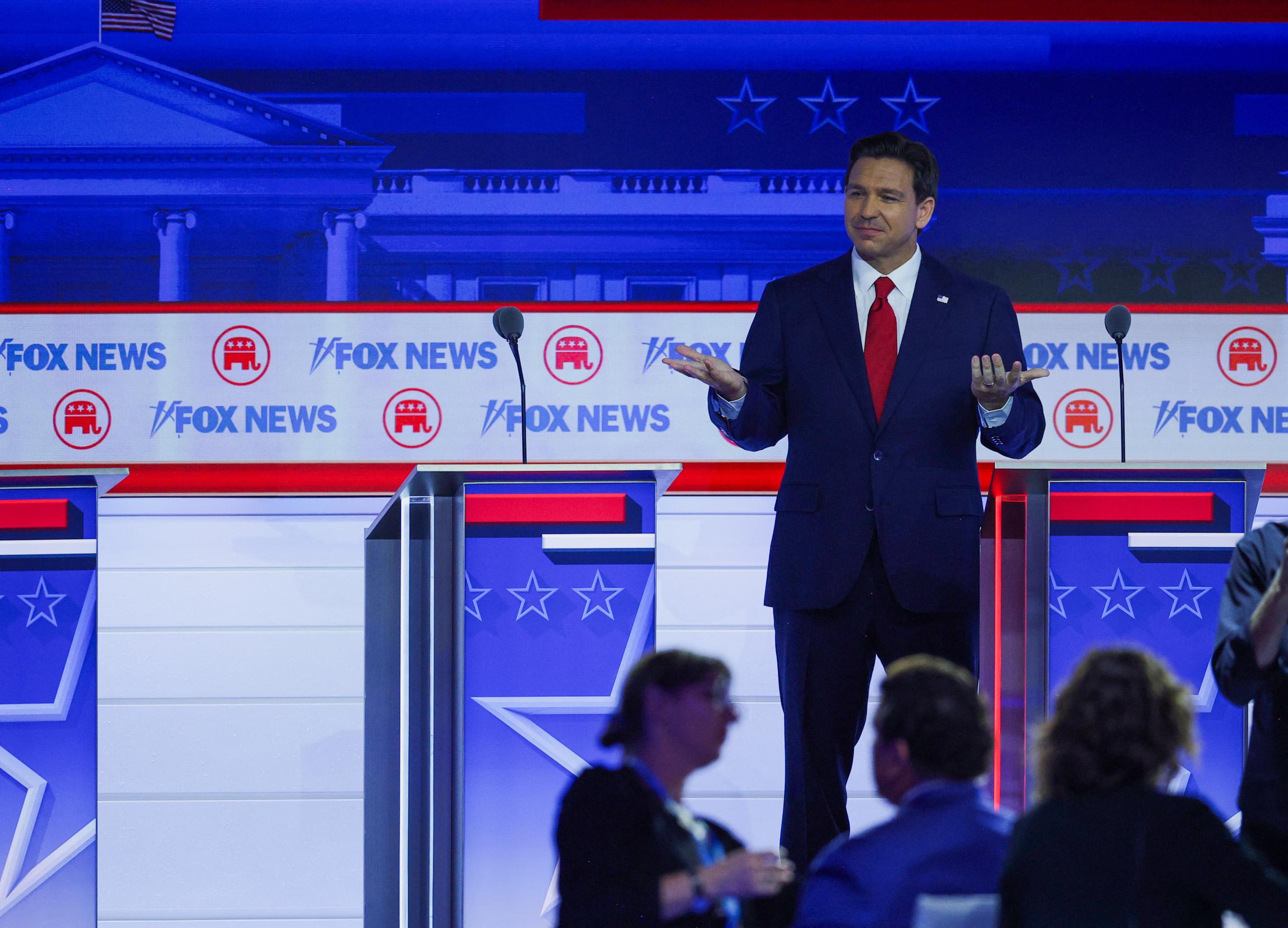

At Iowa fairgrounds, in glossy cable news interviews, and during the first debate stage of the 2024 Republican primary race, Florida Governor Ron DeSantis has made his state's COVID-19 response central to his U.S. presidential campaign.

It is a message focused on what Florida did not do during the pandemic. On the debate stage, DeSantis said,

Why are we in this mess? A major reason is because how this federal government handled COVID-19 by locking down this economy. It was a mistake. It should have never happened. In Florida, we . . . kept our state free and open. And I can tell you this: As your president, I will never let the deep state bureaucrats lock you down.

In short, DeSantis argues that "Florida got it right and the lockdown states got it wrong." His promise as president would be "to make America Florida" when the next pandemic arises.

DeSantis is the only major U.S. presidential prospect still campaigning on how best to protect lives and livelihoods in the pandemic

In recent months, DeSantis has been the only major U.S. presidential prospect still campaigning on how best to protect lives and livelihoods in a pandemic. But that may be changing. This week, President Donald Trump and Governor Nikki Haley each pushed back against school districts encouraging mask-wearing in response to an uptick in infections and COVID-related hospitalizations. As the next Republican debate approaches, Florida's record against COVID-19— including its use of public health mandates—deserves renewed attention.

Data from a recent peer-reviewed study in The Lancet shows that Florida performed well in the pandemic relative to many U.S. states if one adjusts for age and other relevant biological factors. Yet the reasons for that performance are not the ones that DeSantis has highlighted in his campaign.

Florida did well because it adopted early aggressive nursing home policies, testing, and gathering restrictions to slow the spread of the virus—at a higher rate than even most states led by Democratic governors—and promoted vaccination among the elderly. These early policies encouraged Floridians to continue to stay home, get vaccinated, and wear masks at a higher rate than the residents of most other U.S. states even after Florida lifted its health mandates.

However, signs are worrisome that Governor DeSantis's recent embrace of vaccine skepticism may be taking its toll in the state. Pediatric immunizations in Florida have declined since the pandemic started and medical exemptions have spiked to one of the highest levels in the nation. Adult seasonal flu vaccination rates for Floridians have likewise fallen. Those trends threaten to make the Sunshine State more vulnerable when the next pandemic strikes.

An Oranges-to-Oranges Comparison of Florida's Record on COVID-19

As outlined in a recent CFR.org interactive, the health disparities among U.S. states in the pandemic were so large that they seemed more like comparisons of nations. For most of the pandemic, some states, such as New Hampshire and Washington, posted COVID-19 death rates comparable to high-performing Scandinavian nations. The death rates of other states, including Arizona and Mississippi, rivaled those of Russia, Bulgaria, and Peru—the worst performing countries in the pandemic.

Where Florida falls on that spectrum depends on whether the comparison adjusts state-level differences in biological and demographic factors that were outside government officials' control when the pandemic began. On deaths, these factors include age and preexisting rates of health conditions that made COVID-19 outcomes worse. Florida's population is among the oldest in the country and has high rates of cancer, cardiovascular disease, and chronic respiratory illness. The state is also relatively urban; population density thus had a modest effect, especially on boosting U.S. infection rates.

Florida's Ranking on Preexisting Health and Demographic Indicators

Without standardizing for those biological and demographic factors, Florida is in the bottom quartile of states on COVID-19 deaths and nearly the worst state in the nation on infections. In an oranges-to-oranges comparison that standardizes for factors outside states' immediate control, the Sunshine State is in the top quartile on COVID-19 deaths and looks a bit better on infections.

Ranking of Florida's COVID-19 Outcomes

From January 1, 2020-December 15, 2021

Florida Set the Tone Early with Mandates and Vaccination, Floridians Followed

Nearly all states, whether governed by Republicans or Democrats, instituted protective health mandates during the pandemic, including gathering restrictions, mask mandates, and closures of bars, restaurants, and gyms. Most states had such mandates in place between March 2020 and June 2020. The biggest difference among states occurred in November 2020 with the emergence of the Delta variant. At that point, more Democratic-leaning states than Republican-leaning states reinstituted health mandates. Almost no states employed mandated measures after July 2021.

The above figure, based on data from The Lancet study, presents the overall use of mandates across the fifty states. Florida adopted more mandates than most states—even Democratic-leaning ones—early but never reimposed them once lifted. DeSantis expanded testing early, and also isolated and prohibited visitors to COVID patients in nursing homes, avoiding mistakes that some other states had made. In the uncertain early weeks of the pandemic, DeSantis closed public schools and kept them closed for the rest of that academic year. He ordered Floridians to stay at home and closed nonessential business on March 29, 2020, urging Floridians to stay "spiritually together, but to remain socially distant."

DeSantis was one of only four governors to reopen schools in the fall of 2020, but Florida was still otherwise slower to lift gathering restrictions and bar and restaurant closures than most Republican-led states. DeSantis gradually lifted gathering restrictions and bar and restaurant closures in May and June of 2020, but permitted the most populous counties in Florida — Broward, Miami-Dade, and Palm Beach — to opt out of that initial reopening and proceed at their own pace.

DeSantis was at Tampa Bay Hospital to cheer on the first COVID-19 vaccine supplies when they arrived in Florida and when the first dose was administered to a frontline health worker. Florida prioritized individuals older than sixty-five for early doses, even to a greater extent than CDC guidelines recommended. For a time, Florida led the nation with its Seniors First campaign to vaccinate this vulnerable age cohort. When looking at the sixty-five-plus population, Florida had similar, and sometimes faster, ramp-up of coverage of the initial two-dose regimen than in California and New York, according to CDC data.

Vaccine Uptake in California, Florida, and New York for People Aged 65+

Percentage of population with a completed primary two-dose series

What happened next has been well reported (in the New York Times and Vox, among others) and has become the focus of DeSantis's presidential campaign. In the spring of 2021, DeSantis embraced a "medical freedom" agenda in interviews, refused to advocate for booster shots and vaccination of individuals under fifty years old, and later hired a surgeon general known for discouraging COVID-19 vaccination in younger age cohorts.

When the delta variant struck and Florida hospitalization rates surged, DeSantis declined to reintroduce gathering and business restrictions, or to promote vaccination or mask wearing among working-age adults—moves that some other Republican-led U.S. states embraced. Florida closed its state-run testing centers and reduced the frequency of its COVID-19 and death reporting. The same day that the federal public health emergency for COVID-19 was set to expire, DeSantis signed into law a ban on government agencies, businesses, and schools from requiring COVID-19 testing, vaccination, and masks for entry or employment. Its restrictions could apply to emergency use authorization of pandemic-related vaccines more broadly.

What is less well reported, however, is that Floridians continued to maintain the same protective behaviors even after the state-level mandates were lifted. In most states, longer adoption of protective health mandates (such as gathering restrictions, mask and vaccine mandates, and closures of bars, restaurants, and gyms) during the pandemic is associated with higher rates of the associated protective behavior (staying home, more mask wearing, and higher vaccine coverage).

Florida is somewhat of an outlier in that regard. It was actually in the middle of the pack among states in its use of lock-downs—bar and restaurant closures and stay-at-home orders—but ranked low on mask requirements and mandate use overall (mandate propensity). Nevertheless, it ranks in the top quartile of states in The Lancet study for reduced mobility (a measure of people staying home relative to pre-pandemic levels) and better than most states for mask use and vaccine coverage. This may be due, in part, to the continued vigilance of Florida businesses, schools, and cities in maintaining such policies.

Florida's Ranking on COVID-19 Pandemic Policies and Protective Behaviors

In other words, Florida should not be used as evidence that masks, stay-at-home orders, and vaccines did not matter in this pandemic when the reality is that Floridians continued to adopt them even after DeSantis turned away from them.

Medical Freedom and Its Toll on Florida's Future Pandemic Preparedness

Floridians may not be able to rely on the same level of public vigilance when the next health crisis emerges. DeSantis's advocacy of medical freedom, especially for younger populations, may be taking a toll on public health more broadly in the Sunshine State.

Between 2020 and 2022, Florida had one of the largest jumps in the nation in its pediatric vaccination exemption rate for students attending school. Before the pandemic, the state was already below the national average for leading pediatric vaccinations. It has since fallen further to a ten-year state low for kindergarten and seventh-grade vaccinations, however. During the pandemic, U.S. seasonal influenza vaccination rates for adults increased nationally to nearly 50 percent but fell in Florida to 40 percent—one of the lowest rates in the country. If these trends persist and extend to other public health measures, the state will be less safe. That is worrisome in a state vulnerable to climate-related health threats, including outbreaks of locally transmitted malaria and dengue fever.

Pandemic Politics and the 2024 U.S. Presidential Election

Governor Ron DeSantis is running for president on his record during the COVID-19 pandemic. It is good and important that he is doing so.

Doing better when the next pandemic strikes depends on elected officials' being held accountable by voters and the press for how they performed in the most recent crisis. Without that electoral and public accountability, the health benefits of living in a democracy fall away and efforts to pandemic-proof the future will drift back into pre-COVID levels of complacency. Accordingly, the same scrutiny being applied to DeSantis should extend to all 2024 U.S. presidential candidates, a roster stocked with current and former U.S. officials who oversaw aspects of America's pandemic preparedness and COVID-19 response, presidents and governors alike.

In the case of DeSantis, voters will need to decide themselves which version of his leadership is most likely to manifest in preparing for and responding to the next public health crisis. It seems reasonable to assume it is the one on which he is running.