These are still pandemic times — if you're a bird.

We are currently experiencing the largest outbreak of highly pathogenic H5N1 avian influenza (H5N1) since the virus was first identified in China in 1996. This strain has infected a broader range of bird species than any H5N1 on record. Since the current outbreak was first reported in 2021, it has killed fifty-nine million commercial birds in the United States, decimated endangered wild birds, and spread to an unprecedented number of mammal species.

Although H5N1 has a history of infecting poultry and has caused isolated spillover events in humans, this strain is the first to evade the traditional containment measures of isolation and culling, has spread globally, and is now consistently killing its reservoir hosts.

Experts have underscored the importance of increasing surveillance of migratory birds and better assessing the risk for spillover to humans. Attention to how existing poultry vaccinations could be used as a cost-effective preventive measure — and how existing national policies hamper their use — is scantier, however. Some countries have been vaccinating poultry to prevent major economic losses, but outdated trade restrictions prevent major exporters such as the United States, Brazil, and the European Union from employing them. It's crucial that governments reconsider their poultry vaccine strategies.

The United States, Brazil, and the European Union accounted for 71 percent of world poultry exports in 2021

The Resurgence of HPAI H5N1

Although H5N1 is considered endemic in some countries, this is the first H5 strain to evade traditional containment measures. Since October 1, 2021, cases have been reported in at least seventy-nine countries, according to the World Organization of Animal Health (WOAH). This outbreak is unprecedented in the severity and scope of damage to avian species, but it is not exceptional: HPAI is a recurring problem and requires a sustainable policy solution.

In the last twenty years, poultry has become the most consumed livestock commodity in the world, especially in developing and emerging markets. Chickens can be raised in small spaces, in a variety of climates, reach market weight faster than any other livestock, and convert feed to meat more efficiently. Cultivating them could serve as a pathway out of poverty for people in many low-income countries. But to meet demand also requires enormous amounts of trade: the volume of poultry traded across borders is greater than any other livestock commodity and is expected to remain so over the next ten years. The three largest exporters — the United States, Brazil, and the European Union (EU) — accounted for 71 percent of world poultry exports in 2021.

Vaccination—An Effective Intervention

Some countries have embraced the use of poultry vaccines.

Last year, the EU agreed to implement a common vaccine strategy across its twenty-seven member states, lifting previous restrictions to ensure that poultry products and day-old chicks can be traded freely within the bloc. The French government — which spent €1 billion to compensate the poultry industry for massive cullings — will be the first country in the EU to begin a vaccination program. It has ordered eighty million doses and will begin vaccinating ducks this September.

Other countries are adopting this strategy as well. Mexico started emergency vaccinations last year and in Ecuador, where the virus infected a nine-year-old girl, the country outlined plans to inoculate more than two million birds in February 2023.

China has been vaccinating its poultry stock for nearly twenty years and data indicate this effort has reduced infections in poultry and spillovers to people. During the winter of 2016–17, when a strain of circulating H7N9 virus evolved into a highly pathogenic avian influenza, the government introduced a bivalent H5/H7 vaccine for poultry and rare birds in captivity. Its use was associated with a 92 percent reduction in H7 infections among poultry and a 98 percent reduction in human H7N9 cases.

The United States has been more tentative. In 2016, the USDA— whose Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service regulates veterinary biologics, including animal vaccines — developed the Policy and Approach to HPAI (Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza) Vaccination, which allows "H5 and H7 vaccines to be used as a tool for combating any potential outbreak" in the United States. In 2017, the agency conditionally approved the first DNA vaccine for chickens to prevent H5N1. In May of this year, after more than a dozen critically endangered condors died from H5N1, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) granted emergency approval for use of the vaccine. The vaccine will first be tested in North America vultures, a more common species that is genetically similar to condors, to ensure safety and efficacy, but it will not likely be approved for all affected species.

Brazil has opted not to vaccinate because it would inevitably lead to trade barriers

Even though the USDA has begun testing four vaccine candidates against H5N1 for use in poultry, its current position is that biosecurity measures such as wildlife management practices are the most effective tool for mitigating the virus in commercial flocks. Four vaccines are licensed for avian influenza H5 strains but are not approved for the strain responsible for the current outbreak. So the agency is working with state and industry partners to strengthen surveillance and rapidly identify and cull infected flocks, and has not indicated that it plans to vaccinate commercially farmed birds. Were the agency to change its approach, under ideal conditions it would take between eighteen and twenty-four months to produce quantities of vaccine adequate for commercial flocks.

Brazil has taken a similar approach, opting not to vaccinate because it would inevitably lead to trade barriers. The country, which exports poultry and poultry products to more than 130 countries, has reported eight cases in wild birds. Close to $10 billion in exports would be at risk if the virus were reported in commercial flocks. Brazil's meat trade lobby, the Associação Brasileira de Proteína Animal (ABPA), last month stated its support for vaccine efficacy studies. Brazil has taken on a growing role in the global supply of poultry and eggs, and importers ban chicken and turkey meat from countries reporting virus in commercial flocks. ABPA has also expressed its opposition to trade barriers on countries that adopt a vaccination strategy.

Given that poultry vaccines have been shown to work, why aren't more countries using them?

Outdated Trade Restrictions

Although vaccines are protective, they make it more complicated to identify outbreaks because one must differentiate whether a bird is infected or has antibodies against influenza due to prior vaccination. Some countries have resisted vaccination because they worry that trading partners will impose barriers on their exports. For example, during the H5N1 2015 outbreak across twenty-one U.S. states, fifty countries banned all U.S. poultry products at various points in the outbreak. Countries free from the virus would not want to import an infected bird and risk subsequent spread to commercial poultry or wildlife.

Countries are also concerned that vaccines that confer partial protection from infection of new viral strains could still allow birds to transmit infection without clinical presentation of illness, and that vaccination campaigns could induce a false sense of security among farmers, who might then relax other biosecurity practices. Countries that have decided to vaccinate their poultry products do so mainly to protect and maintain domestic supply chains, not trade.

However, several advances in vaccine technology can address these concerns and should be considered alongside strong surveillance programs as countries revisit and update vaccination policies and strategies. Policy change may be under way. On May 21, WOAH Director General Monique Eloit recommended that governments consider vaccinating free-range poultry against bird flu, mainly ducks, a contrast from the organization's long-standing approach of culling infected flocks. However, a WOAH survey showed that only 25 percent of its member states would accept imports of products from poultry vaccinated against HPAI, an indication that advances in vaccine and surveillance strategies need to be more widely socialized.

Recommendations

It is imperative that current trade policies are evaluated and revised to reflect the new scientific reality. This can only happen if more people understand that vaccines are safe and effective and that vaccinated birds can be distinguished from infected ones. Change, particularly to strengthen public health, is possible.

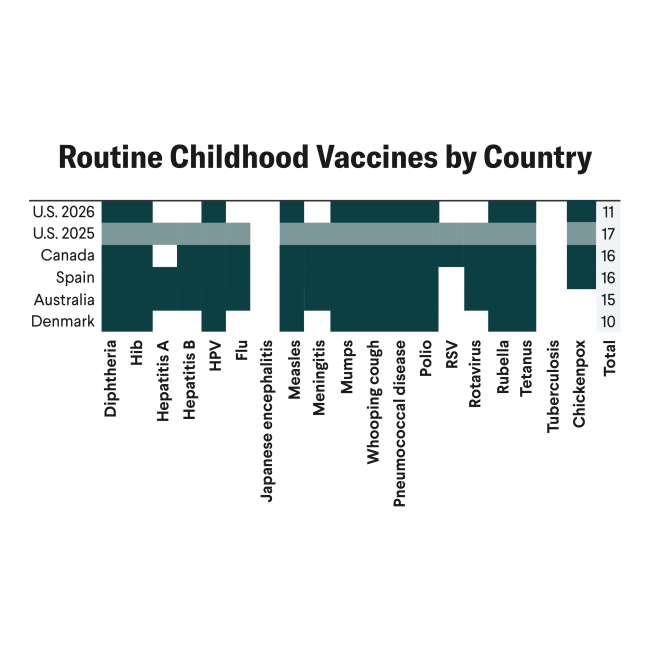

Seasonal influenza vaccinations for humans are routine and recommended by the World Health Organization. Poultry, particularly in the United States, receive several vaccinations in the first days of their lives and are treated with antibiotics before going to market. The United States should use this outbreak and changes to national vaccine policies to learn and to advance our approach. It is obligated to gather data on the efficacy and safety of current vaccine platforms to protect avian species, provide a safe mechanism for meat and egg production, and contain a highly pathogen virus that has spilled over to an unprecedented number of mammals including humans. Trade negotiations and educational outreach focused on making poultry importers comfortable with products from vaccinated poultry would be a major win for global health. The science should inform discussions on policy review and hopeful revisions to both ensure global food security and contain a highly pathogenic avian pandemic.