After facing down the COVID-19 pandemic and shouldering the massive logistical challenge of bringing a vaccine to 7.5 billion people—not to mention the ongoing difficulties of aging populations, rising health-care costs, and falling development assistance for health, all amid chronic workforce shortages—health workers finally seem to be getting the attention they deserve. We see outpourings of thanks and applause for health workers, and greater recognition of their sacrifices.

But in order to be better prepared for the next crisis, the health workforce needs more than just appreciation. Health workers obviously deserve decent pay and safe working conditions but their industry also needs systemic change, including less hierarchy and more decentralization of power within the health workforce. A greater valuation of the nursing profession provides one pathway towards equity in health-care leadership and systems that truly deliver for people.

Power hierarchies in health care are common to every health system, in every country.

Whether in vaccination programs, outpatient clinics, or hospitals, health care is delivered by teams of providers. Yet, the power distribution on most health-care teams is far from equal and tends to mirror inequities that are embedded in the larger health and social environment. Doctors are seen as being in charge, while nurses and paramedical staff are expected to follow their lead. Without intentional policies to flatten hierarchies and promote collaborative practices, these power dynamics limit quality of care and the accountability of health care to communities.

Power hierarchies in health care are common to every health system, in every country. Although intended as a functional structure for training and practice, they can quickly become dysfunctional. Decision-making authority within health-care organizations is formally ranked by level and type of training. These distinctions are reinforced by gender stereotypes associated with specific roles and discrimination that limits career progress for women in particular, both of which are persistent in the health professions. Further compounding this, physicians, nurses, technicians, and other health providers are trained in siloed environments, and develop parallel professional cultures, languages, and communication methods. As a result, many new providers enter the workforce without sufficient experience in communicating with other disciplines and navigating power relationships. Studies by the Joint Commission, which provides accreditation and patient safety standards for health-care organizations, have found that communication failures among health-care professionals are a leading root cause of unanticipated patient death and injury in health care. Fear of questioning superiors can result in failure to challenge incorrect clinical decisions or follow safety protocols.

Interprofessional collaboration (IPC) skills for health-care providers are designed to improve communication and help dismantle harmful hierarchies in the provision of health care. Education in IPC often involves simulation training: a patient-actor experiences a medical emergency that requires the team to make a decision under pressure, or an individual faces an instance of disrespectful communication in a professional interaction. During simulations and subsequent debriefings, participants of all disciplines and training levels are encouraged to freely share their perspectives, and junior members of the team may need to disagree with senior colleagues. This type of training emphasizes the non-clinical aspects of team-based care, including mutual respect, overcoming power differentials, and prioritizing the patient's perspective. Teams trained in IPC not only have improved patient outcomes and efficiency, but also greater career satisfaction among individual team members.

Nursing education generally includes teamwork and learning to work in collaborative environments. Nursing schools, in particular, emphasize IPC training because nurses are reliant on these skills. Nurses are often responsible for translating between patients and members of the health-care team. A nurse is often the first to respond to changes in a patient's health status. Interprofessional training programs led by nurses are increasingly being introduced in medical schools to promote collaborative practice-ready physicians. Studies have shown that physicians and nurses often view this collaboration differently, with physicians, especially older physicians, undervaluing IPC.

Teams trained in IPC not only have improved patient outcomes and efficiency, but also greater career satisfaction among individual team members

In 2010, the World Health Organization (WHO) identified IPC as "an innovative strategy that will play an important role in mitigating the global health workforce crisis." The WHO noted that structural factors influence the development of an interprofessional workforce; management practices, selection and promotion of collaborative leaders, and the laws governing health professions have the potential to transform health systems and enable interprofessional education and practice. Just as the IPC-trained health-care team responds more effectively to critical patient-care situations, these human systems adapt to emerging crises that challenge the resources of healthcare globally, such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Nurses, with their particular expertise in IPC, are critical stakeholders in reenvisioning health systems and building and empowering collaborative workforces. Nurses are playing, and will continue to play, vital roles in the pandemic response and recovery.

There are 27.9 million nurses globally, accounting for 59 percent of all health professionals. The vast majority of nurses—more than 70 percent—are women. The WHO's State of the World Nursing Report 2020 highlights the need for more investment in nurse training, and better salaries and working conditions for nurses. This means promoting and empowering nurse leaders, and tackling the barriers to women in health-care leadership in general.

Nurses are more likely than physicians to be trained to communicate with multiple stakeholders in promoting quality and safe care for patients. Nurses, compared to doctors, are more likely to be thought of as peers by other non-physician providers and by patients. They are embedded within their local communities, sharing cultural traditions, norms, and values with their patients. Their communication skills, interaction, assessment, and recommendations are critical to the health care team and larger community.

The COVID-19 pandemic is testing the interprofessional communication capacity of health teams, and nurses are filling the gaps. As a New York Times documentary revealed, nurses are spending long, isolated hours at the bedsides of critically-ill patients, keeping physicians informed and contacting families who are not permitted in the intensive-care wards. In other cases, nurses have been required to move among different health teams, adapting constantly throughout the pandemic. Matthew Crecelius, a U.S. based intensive care unit travel nurse, said, "As guidelines for the treatment of COVID-19 have evolved since spring of 2020, communication between critical care teams and bedside nurses has been frequent and direct."

As we enter a new and more hopeful chapter of the pandemic, we have an opportunity to do better by our nurses and the health teams that rely on them

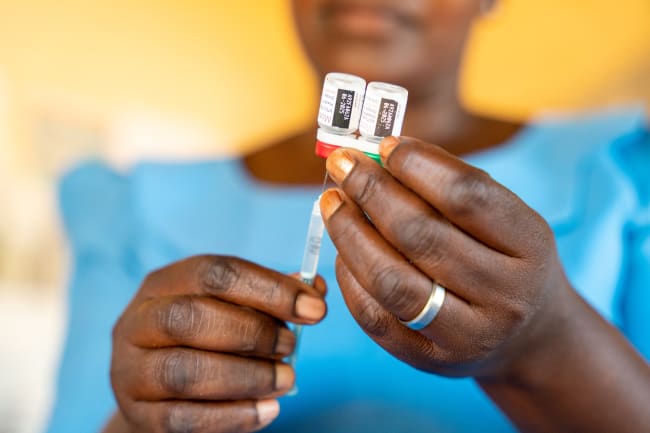

In the United States, many nurses are modeling public health communication about the COVID-19 vaccine. In an appeal to communities disproportionately affected by the pandemic, nurses and other health-care providers of color have often been the first to be vaccinated, signaling to their communities that the new vaccines are safe, effective, and needed to suppress the vicious cycle of grief and despair being felt by millions. This is true of nurses around the world, who are working at the primary levels of care and are responsible for dispelling misconceptions about the virus and vaccine, and for bringing health information to marginalized communities. As we continue to roll out vaccines to the public at large, communication and a collaborative lift from all health cadres will be essential in changing negative perceptions about the vaccine, expanding roll out, and turning "vaccines into vaccinations."

To manage the pandemic and strengthen health systems to meet ongoing and emergent challenges, interprofessional health teams with nursing and other diverse leadership should be at the center of the health policy agenda. Interprofessional collaboration—including communication that transcends medical hierarchies and advances patient-centered care—should be considered an essential leadership competency, and education in IPC, a requirement for all health professions, including physicians. Policies in public health departments, hospitals, and other care settings, should be reexamined to ensure that they better support nurses, women, and other underrepresented health providers in leadership roles and strengthen collaboration among professions.

Those with interprofessional training and ties to communities—including nurses, midwives, and community health workers—must be invited to advise on existing and new policy and regulation that influences their decision-making authority and compensation, and impacts care delivery. None of this can be implemented without a strong foundation of basic protections for health workers' rights, among them equitable COVID-19 vaccine distribution and gender transformative policies that prevent discrimination and harassment and ensure safety and quality of life in and outside the workplace.

In an effort to recognize the unique roles that nurses play in various healthcare settings, the WHO dubbed the year 2020 the "Year of the Nurse and Midwife." The tragic irony that the celebratory year was marred by a pandemic— one that has taken the lives of thousands of nurses and other frontline workers globally—was not lost on the nursing community. As we enter a new and more hopeful chapter of the pandemic, we have an opportunity to do better by our nurses and the health teams that rely on them. Raising the profile of interprofessional collaboration and communication—and the nurse leaders who embody these skills—is essential in ensuring that health care providers and systems survive and thrive post-COVID-19.