We tend to think of poor countries as rural places and more economically advanced nations as places that are more urbanized. That impression influences the way local politicians and foreign aid donors discuss and design programs to address the health care, infrastructure, and other social and economic needs of impoverished people.

Click on a promotional video for a global health charity or flip through a glossy brochure for an international development NGO and you will find they tend to feature the same sort of images: hopeful children and grateful parents in a dusty, rural village under a big blue African (or South Asian) sky. Cities and towns don't fit that picture. Aid programs in sectors such as water, sanitation and hygiene historically have not been designed with the needs of the urban poor in mind. There has been less international assistance for health conditions prevalent in urban settings, such as noncommunicable diseases and pollution-related illnesses, relative to the diseases and conditions more generally associated with the rural poor.

A new harmonised method estimates that the world is 74 percent urban, while the UN estimate is 55 percent.

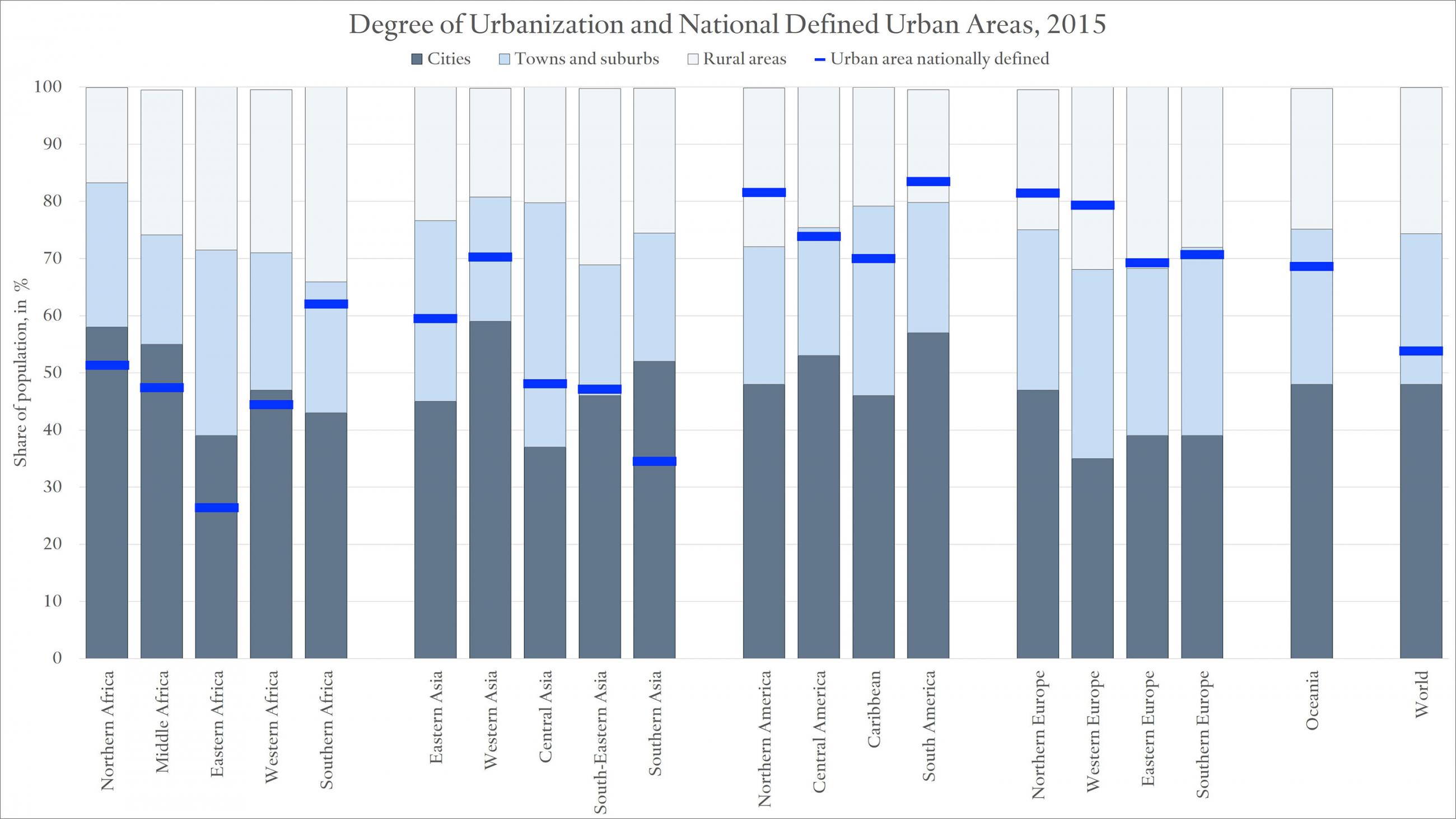

New research from the European Commission (EC) and several international organizations suggests, however, that the United Nations (UN) World Urbanization Prospects, long considered the authoritative measure of global urbanicity, has grossly underestimated the share of people in Africa and Asia who live in towns and cities. Using a combination of high-resolution satellite imagery, remote sensing, and census data and a new method called the Degree of Urbanization, a team of researchers led by Lewis Dijkstra, estimates that East Africa and Southern Asia are roughly twice as urban as the UN data indicate. In contrast, these researchers find the national definitions of urbanicity in the Americas and Europe differ little from those produced with the geospatial data. The same is true for cities with more than 300,000 inhabitants—both the UN and this new method produce similar numbers.

The gap between this new harmonized method and UN data estimates comes down to their differing classifications of smaller cities and towns, primarily in Africa and Asia. But, the people in these smaller settlements add up to large numbers. Overall, the new method finds that the world is 74 percent urban with 5.4 billion living in towns and cities, while the United Nations estimates that the global share of city and town dwellers is 55 percent and includes 1.3 billion fewer people than this harmonized estimate.

What is a City?

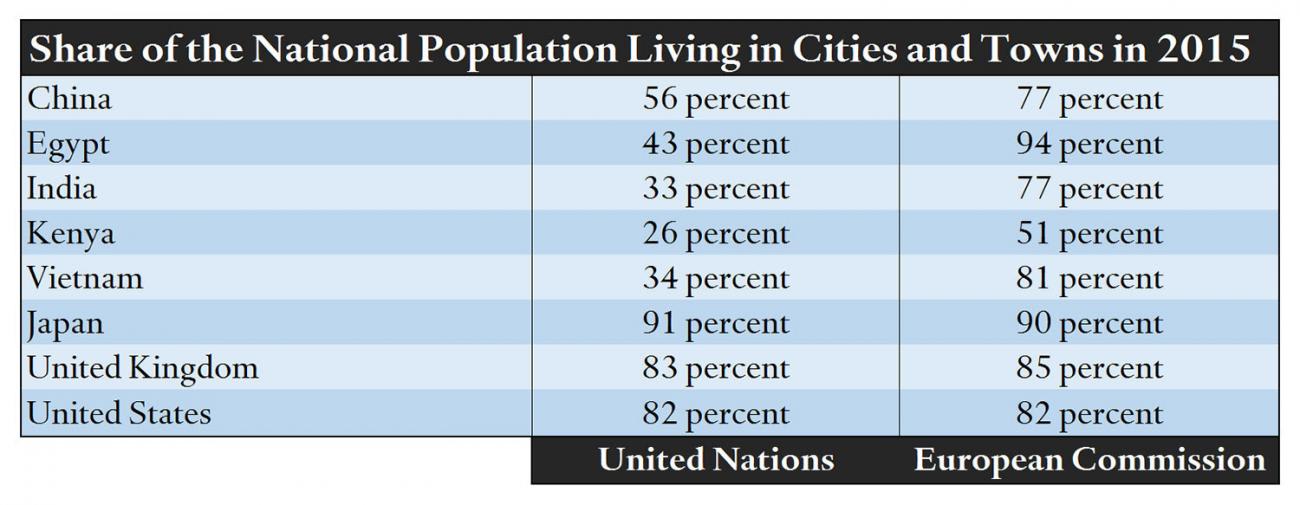

What explains the differences between the UN and European Commission classifications of smaller cities and towns? The UN World Urbanization Prospects relies on data that countries self-report based on their own national definitions of urban settlement, and those definitions vary widely from country to country. Most countries have administrative designations for the boundaries of cities, which do not necessarily reflect the on-the-ground demographic reality of those urban settlements and cannot be compared across countries. Some nations supplement these administrative designations with other statistical requirements. For example, India defines an urban area as a settlement of 5,000 inhabitants where at least 75 percent of males are not working in the agricultural sector. While the United States starts classifying settlements as urban when they exceed a population threshold of 2,500, China and Egypt set their minimum threshold for their cities at 100,000.

The practical differences in these national definitions were well-illustrated when Dijkstra and his European Commission colleagues sought to match the national self-reports of urbanicity with their estimates of population density, which were generated with high-resolution satellite imagery and national census data. To match India's self-reported level of urbanicity (33 percent), these researchers had to apply a minimum population density threshold of 16,705 people per square kilometer—a high level of urban density that many global cities (such as my city of Washington, DC) do not meet. In contrast, a population density threshold that is seventy-five times lower (222 residents per square kilometer) reproduced the U.S. self-reported level of urbanicity—82 percent.

An effort to develop a more globally consistent definition of cities and settlements…

In 2016, European Commission researchers, working with the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the World Bank, launched an effort to develop a more globally consistent definition of cities and settlements. Their project layers a global population grid on top of geospatial census data, using satellite imagery and remote sensing to detect buildings and estimate population size and density. The European Commission applies a global definition of settlements to a global population grid with one square kilometer cells, based on the following criteria:

- Cities have the majority of their population in urban centers, which are defined as having a total population of at least 50,000 and consisting of contiguous grid cells with a density of at least 1,500 inhabitants per square kilometer.

- Towns and suburbs do not meet the thresholds for being cities, but have a majority of their population in urban clusters, which are defined as having a total population of at least 5,000 and consisting of contiguous grid cells with a density of at least 300 inhabitants per square kilometer.

- Rural grid cells have the majority of their population outside of urban clusters.

This standardized global definition produces substantially different results than those of the UN World Urbanization Prospects. Overall levels of urbanization in many African and Asian nations are not much different from Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

Note: Numbers in the table above comes from UN Urbanization Prospects and European Commission data.

There are limitations to these results. The European Commission researchers acknowledge that their results may be less reliable in areas where census data are of poor quality because remote sensing and satellite imagery cannot confirm census counts. In an email communication to me, Dijkstra pushed back, however, on critiques of the European Commission results that argue cities cannot have higher levels of farm employment or croplands "because agriculture also occurs outside rural areas… [and croplands] are normal features of peri-urban areas." In 2020, the UN Statistical Commission is expected to consider formally recommending the Degree of Urbanisation to be used for international comparisons.

A Global Definition of Cities Means Better Understanding of Local Urban Health

While small cities and towns of Africa and Asia have not been "lost" to their inhabitants and governments, when classified as rural, these urban settlements have been missing from the data that drive our understanding of health, social, and economic consequences of urbanization in these low- and middle-income nations. When these small cities and towns are included in those analyses, a better picture of the drivers and consequences of urban-rural differences emerges.

A forthcoming report by Vernon Henderson, Vivian Liu, Cong Peng, and Adam Storeygard uses these geospatial data on urbanization to assess the differences in health, education, and fertility outcomes in rural areas, towns, and cities in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. This analysis is based on demographic health survey data for these regions, which are also linked to GPS coordinates for the clusters of survey respondents.

Some of the results from this study align with the expectations of health researchers. In sub-Saharan Africa, urban households are three times as likely to have access to safe water and electricity and twice as likely to have access to improved sanitation as their rural counterparts. Except for piped water, where provision is not keeping up the rapid population growth in African cities and towns, access to essential infrastructure is improving on most measures.

Obesity rates were 2.3 times greater and fertility was 50 percent lower in sub-Saharan Africa cities.

Some of the study results, however, are more surprising. There were only modest differences between rural and urban settings in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia on many traditional measures of global health: infant mortality, deaths from diarrheal disease, and vaccination rates. When controlling for individual and household levels of education, gender, and age, those differences largely disappeared, suggesting that urbanization is neither the cause nor solution for those conditions. In contrast, obesity rates were 2.3 times greater and fertility was 50 percent lower in sub-Saharan Africa cities than in rural areas, and controlling for educational, age, and gender differences did not fundamentally change those results.

Global Health is Urban Health

There is one area where the UN and this new harmonized approach agree: the share of population in cities and towns globally is growing and likely to continue to do so. The United Nations projects the population of city dwellers globally to grow by 2.5 billion by 2050, with nearly 90 percent of growth occurring in lower-income nations in Africa and Asia. The UN Sustainable Development Goals include targets for making cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable. It is past time that the international aid programs adapt their rural-focused programs and narratives to reflect that objective. The residents of the hidden cities of Africa and Asia deserve the same lifesaving support afforded to those children in that rural, dusty village.

EDITOR'S NOTE: This story was updated from an earlier version to reflect the larger group of organizations that collaborated on the new harmonized approach to a globally-consistent definition of cities.