Social media lit up—including the accounts of many a public health professional—earlier this week after U.S. President Joe Biden said in an interview with 60 Minutes that the COVID-19 pandemic is "over." We asked Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) Director Christopher Murray whether he agrees. Plus, we tapped into his expertise as a physician and global health professional for his take on the new omicron-variant COVID-19 vaccine, including who should get it and when, and what flu season might hold this year.

□ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □

Think Global Health: Let's start with President Biden's comment on 60 Minutes, that COVID-19 is over. What are your thoughts on that? And what is your own answer to the question?

Christopher Murray: That's an easy one. I wrote an article in The Lancet nine months ago that said the pandemic was over then, so I agree with the President. It's about what do we mean by a pandemic. What I meant, and what I think the President means, is an era of extraordinary emergency measures—not that the disease is going away. Because it's not.

We can think of it as endemic—that's probably the right way to think about COVID at this point

We were just looking at the data. In the United States, for example, there are very few mandates after February 15 [2022]. There were one or two states that kept the mask mandates on for a couple of weeks after that. But after that, we've basically had nothing. Europe's been a little slower to get rid of them all, but it's been a pretty steady shift away from an emergency view of COVID. If that's what we mean by a pandemic.

Now, WHO has a legal definition of a pandemic, which is a disease that's spreading all around the world, which COVID still is. But to the extent that we have infection everywhere, don't expect it to go away. We can think of it as endemic, and that's probably the right way to think about COVID at this point.

Think Global Health: Is there anywhere on the planet where it feels like there is still a pandemic?

Christopher Murray: China. Overwhelmingly China, because they are pursuing their zero-COVID strategy, and they have a population over eighty that has relatively low vaccination rates. And so what happened in Hong Kong can easily happen in mainland China, even with omicron. So that's the place where the emergency measures are in place and are likely to stay that way.

There are a bunch of countries that are still pursuing some measures, like mask mandates and screening travelers.

Think Global Health: Can you give a couple examples?

Christopher Murray: I just was recently in Peru and they have mask mandates in place. They have various testing requirements and quarantine requirements.

Think Global Health: What's the outlook for COVID-19 in the United States right now?

Christopher Murray: What we're expecting is that starting sometime in October, infections will start to go back up driven by two factors—one is immunity wane. So, we've got an omicron BA.5 wave through the summer, and that protection against repeat infection will start to wane. And now we know that immunity against infection wanes quickly, whether from vaccination or infection.

So [this fall and winter] we will have more and more people available to be infected coinciding with people being indoors more in fall and winter. So, we expect infection to go up.

The good news is that protection from severe disease and death lasts much longer, and so we don't expect an equivalent increase in severe disease and death, added to which there's Paxlovid [the COVID-19 antiviral] available. So that also has a moderating influence.

Think Global Health: How will the numbers look in the United States?

Christopher Murray: The numbers will look scarier to some because we still are struggling in this country to distinguish people going to hospital and dying with COVID from people going to hospital and dying from COVID. And so, we will see numbers that will make a lot of people anxious in the fall and winter. But maybe there will be more pressure to separate those two categories out. Maybe we'll start to get a better sense of who's actually dying or severely ill from COVID.

The [Paxlovid] trial was in people who were unvaccinated and never infected. And that group of people doesn't exist anymore, except in China in certain cases. So we don't know one hundred percent about the incremental gain from effects of Paxlovid in those with some immunity. Probably, it'll start to come out from researchers doing studies with real world evidence—studies from medical records—one would hope.

In some ways, we know less right now than we did a year ago, because the data is getting harder and harder to interpret.

Think Global Health: Is it possible COVID-19 hospital admissions will be lower in the months ahead?

Christopher Murray: Yeah, people think of hospital admissions as a measure of severe disease, but right now, it's not. It's actually just a measure of community transmission. We actually have some pretty compelling evidence of that in the U.K., where they know true infection rate because they do every-two-week surveys. They are the only country in the world that has really great data about infection because they go out and measure it. We could have done this but we haven't. If you just draw their infection curve through the whole pandemic, and then put it on top of the curve for hospital admissions, the curves almost perfectly match. And that's because there, at hospital admission, everyone's required to be tested when you get to the hospital. Hospital admission becomes a measure not of severe disease but of transmission in the community.

I was recently in Peru and they have mask mandates in place. They have various testing requirements and quarantine requirements

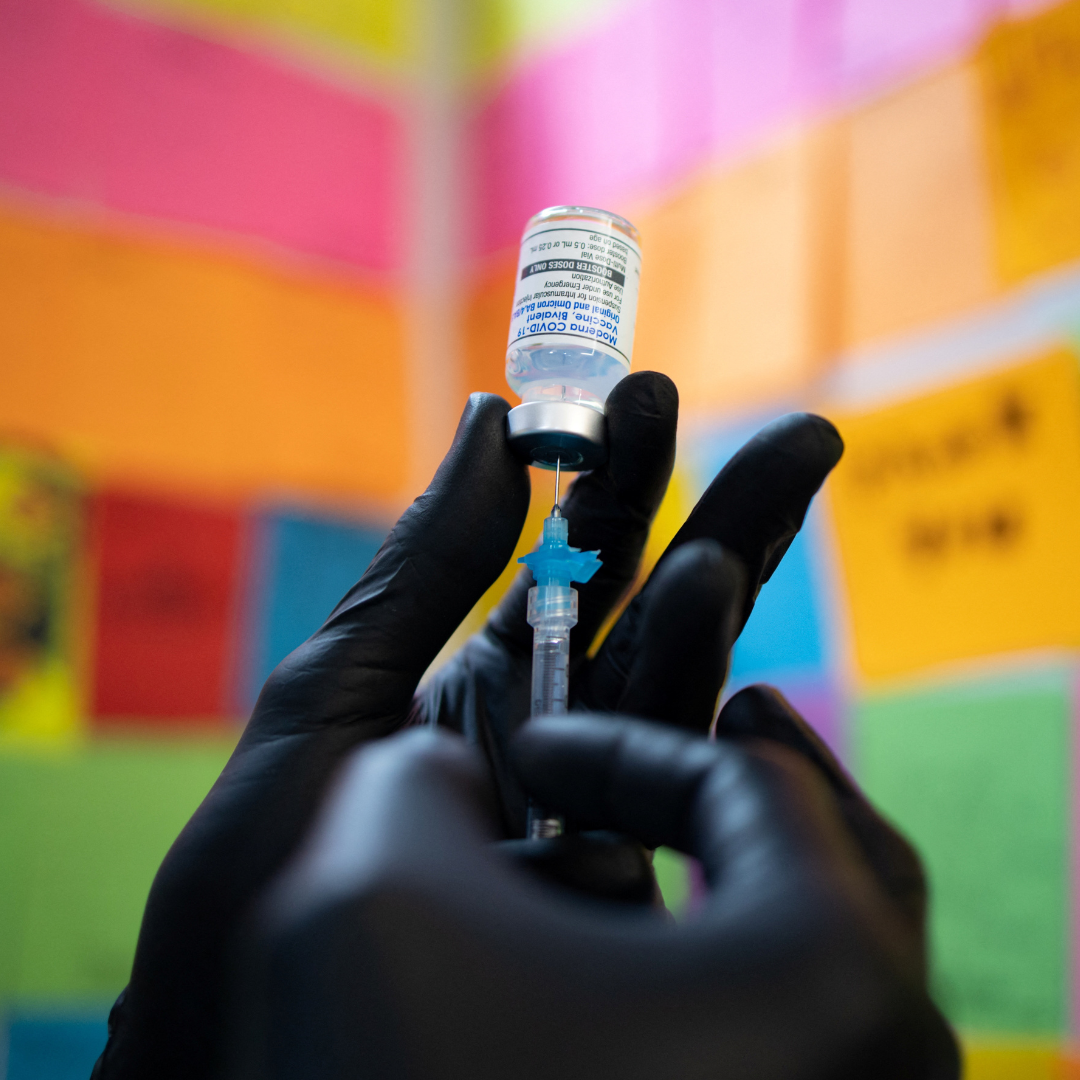

Think Global Health: Let's talk a little about the new omicron vaccine. What is your recommendation for when to get it?

Christopher Murray: We had a vaccine that was designed for the ancestral variant. The mRNA vaccines are focused just on the spike protein. It's not a broad target. Some of the other vaccines, like AstraZeneca, are broader. But the ones that we use are focused on spike protein. The spike protein is mutated multiple times. Fortunately, we're still getting good protection from severe disease for delta.

Re-engineering the vaccine to reflect what's in the circulating variant—at least the circulating variant from over the summer—is likely a very good thing. It will give protection against those variants, or better protection. And hopefully, by having both in there [in the new vaccine], it will continue to have some protection if we see some delta lineage subvariant emerge or somehow become a threat.

Think Global Health: Do you recommend everyone who qualifies to go get the omicron vaccine?

Christopher Murray: I would recommend people who have not been infected with BA.5 in the last two or three months to get it. And then for those who have been infected more recently, just wait for that window where you could probably get a pretty decent infection—then get the new vaccine.

Think Global Health: Can you get a flu vaccine and a COVID-19 vaccine together?

Christopher Murray: I know of nothing that says you shouldn't get them together—no actual data. People have opinions, but we don't really know anything about that. Flu vaccines aren't great [protection-wise]. Unlike COVID vaccines—which are great, incredible protection against severe disease—the flu vaccine averages in the last decade maybe 35 to 40 percent protection. It's better than nothing, but it's not a game changer for flu. Lots of the flu experts have been expecting a bad flu season after these almost nonexistent flu seasons, so it would not surprise me if we have a bad flu season.

Think Global Health: Any final parting thoughts?

Christopher Murray: I tend to think these days that we need to be planning for two cases. The case where we see maybe new omicron subvariants that may or may not have some immune escape, like BA.5, but where we won't see a huge impact or anything that'll trigger behavioral change or policy response. It will be a question of keeping up vaccination and making sure antivirals are available. So that's probably the dominant scenario—what we hope for and expect to see because of immunity waning. This [COVID] is a permanent thing where it's probably just going to be around forever because the immunity just isn't sustained.

And then the other scenario is where a variant comes along that is more severe—not necessarily more transmissible—but more severe. And it has immune escape, meaning it can infect people who have been recently infected or vaccinated. And that's a much lower probability scenario. But if it occurred, suddenly we would be in a very different situation, where probably some governments would be intervening, not just managing it through vaccination and antivirals.

To prepare for that lower probability scenario, there's a lot we should know. We shouldn't be caught surprised, right? We should keep up surveillance. We should have a playbook that says, if it happens, here's what we'll do. Planning for that lower probability scenario is super important so that we don't repeat the mistakes of the past.

Think Global Health: Do you think we're going to do that?

Chris Murray: I don't. I fear we won't. I think people are so caught up in the moment and so many people have moved on from COVID to other topics. I fear we are not learning the lessons we need to, including which part of what we did worked. Which of the mandates that we put in place worked? Which ones had the greatest impact? What sort of testing regime was useful? All those things—we should be doing a very detailed retrospective to understand what should be in our future playbook. The federal government should be taking a lead and then helping states and counties have a plan for when a bad variant shows up. And if we never use it, so be it. But it's better to be prepared than caught either napping like we were for delta, or perhaps over-responding like we did for omicron.