I am a physician, an epidemiologist, and a mother from Windhoek, Namibia. This is a snapshot of my week.

Sunday:

Dad gets admitted with COVID-like symptoms to a private hospital. He has underlying chronic kidney disease and a gastrointestinal stromal tumor and has not been vaccinated. We wait for five hours at the emergency unit before he is admitted. His attending physician does not give any feedback. When I contact her, she says she is too busy to talk. The next day, she hands him over to another doctor. We find out from a colleague that dad's COVID test is positive.

Monday:

A friend is unable to get a contraceptive shot at the primary health-care clinic; it is out of stock. I buy it at a private pharmacy and inject her but wonder about all of the other "COVID babies" who are now on their way.

Our household goes into quarantine. My husband moves out; a German colleague is visiting, and he does not want to transmit the virus to him.

Tuesday:

The daughter of a friend has a motorcycle crash and a traumatic amputation of her forearm. My husband, a spinal surgeon, arranges a helicopter lift, first to the capital where blood flow is restored and bones grafted, and then onward to Cape Town, South Africa, for nerve repairs. She survives. Her arm does not.

Dad gets discharged into isolation at our house. I am now the single caregiver of three small kids and an invalid, cooped up inside. We have not been vaccinated.

Wednesday:

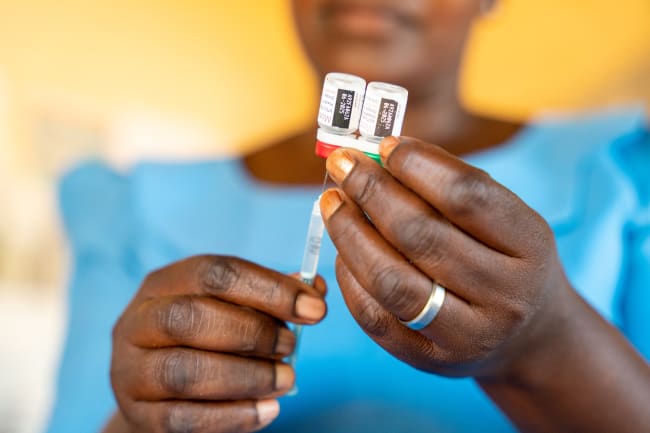

A friend goes for the COVID vaccine at the public hospital. She can choose between AstraZeneca and Sinopharm. I recommend Sinopharm since we have a variant in the region against which the AstraZeneca vaccine is reportedly not as effective. Hours later, the media reports Europe will not let individuals who had the Sinopharm shot travel this summer.

Mom gets admitted to a private hospital with an infection from her dialysis catheter, and possibly COVID. We wait for two hours at the reception area of the first hospital, then get told they do not have a "COVID bed," even though she tested negative two days ago. We move to another private hospital where we wait another two hours. The nurses are "handing over" to the next shift. I set up the IV-line to get her antibiotics and pain medication running.

Thursday:

An employee on my brother's farm goes to the primary health-care clinic—he's had a chronic cough and weight loss for more than three weeks. He is sent home with paracetamol (acetaminophen). My brother takes him to the private general practitioner (GP) in town and a chest x-ray shows he has pulmonary tuberculosis (TB). He starts on treatment at the public hospital but does not have bed linens or food. His wife and children are not screened for TB. Neither is my brother.

I submit a fellowship application. My children's screen time is up to three hours a day.

Friday:

Mom goes back to the first no-COVID-bed hospital in an ambulance for dialysis. But the ambulance does not leave until her medical aid confirms she has health coverage.

In the news, we hear that the Biden administration reports their support for waiving international patent protections for COVID vaccines.

Dad gets an intravenous iron infusion at a private GP. The GP asks why I am still not doing any clinical work—only research—even though I trained to be a clinician. I respond, asking if he knows how many clinical epidemiologists we have in country, but wonder quietly to myself if I am a cop out.

Saturday:

I pick up Dad's prescription at the pharmacy and overhear a conversation between a pharmacist and a client. The client complains about a loss of taste and smell, and general malaise. The pharmacist prescribes paracetamol and an antihistamine. She does not refer him for COVID testing.

The African Union reports the procurement of around 400 million doses of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine for African countries. Only five countries have placed an order and submitted their deposit. Our country is not one of them.

I submit a COVID seroprevalence survey protocol and a TB response plan for a mining company.

Reflections on My Week and Health Care

My head is spinning between the dual responsibilities of being a mother and a doctor—taking care of my children and my parents, and making sense of it all as a researcher—and processing the daily overflow of pandemic information.

There are numerous issues in ours and other developing countries that demand attention: collectively, we have to isolate and not transmit this virus. As a state, the continuity of primary health-care services during the pandemic and the procurement of vaccines is pivotal. And the contrasts between the private and the public health-care systems (although neither are particularly effective) need to be addressed.

And who cares about those of us who are supposed to care?

Who cares about those of us who are supposed to care?

I did not write this either to shame or to blame, but rather to highlight—through my own personal experiences—the challenges we know exist in our health and social systems, which have been put into stark relief by the pandemic. Women in particular are currently facing an extraordinary number of responsibilities and, simultaneously, barriers to health care and good health.

The two places that require focus in order to bring about improvements to health care: inequality, including gender, health, and economic inequalities; and insufficient capacity, in the health-care sector, in households, and in social systems. On a philosophical level, both challenges can be addressed by creating freedom of choice. On a pragmatic level, it means women, minority groups, and the poor need to be empowered to be able to make their own informed decisions without being constrained by external parties.

A strong base for empowerment is education, but good education is not enough. It needs to be founded in rights-based policies for health, education, and economic sectors. In addition, rights-based policies, especially during but not exclusive to the pandemic, need to be anchored in community awareness, so that we realize we are also responsible for those around us.

Although international support would be of paramount importance to overcome current and long-term effects of the pandemic, we must use our internal individual and collective resources fairly, ensuring good governance and transparency. Inequality and disparity will only be addressed if those who are disproportionately advantaged join the conversation.

The views expressed in this article belong solely to the author and do not reflect the opinions of her employers/affiliate organizations.