The most effective strategy that can enable ending the pandemic and reinvigorate the economy is vaccinating as many people as quickly as possible. By early April, more than 567,000 Americans had died of COVID-19, a toll that exceeds the number of soldiers killed in World War II. Now, several universities and the state of New York have mandated COVID vaccinations, a move that legal scholars argue could likely be legal. But these organizations and others will need tools to verify a person's vaccine status, a proposal that has become mired in partisan controversy.

Research my colleagues and I conducted in cancer care shows that health-care innovations can exacerbate disparities because socio-political factors often curtail access to these innovations, a process we described as the "direction of diffusion." This creates two sets of patient populations: those with access and those without. These inequities in access are frequently concentrated in underserved communities, and can be difficult to overcome unless a proactive approach is pursued. Our research is relevant to mitigating inequities in COVID-19 vaccination campaigns because politicization of vaccine verification efforts will negatively impact access in underserved communities.

By early April, more than 567,000 Americans had died of COVID-19, a toll that exceeds the number of soldiers killed in World War II

Developing a means of assessing COVID-19 vaccination status will require contributors from multiple disciplines, and it is incumbent that it be focused on producing equitable health outcomes. It will hinge on more effective messaging, incorporating ideas from behavioral economics, and building equitable access programs.

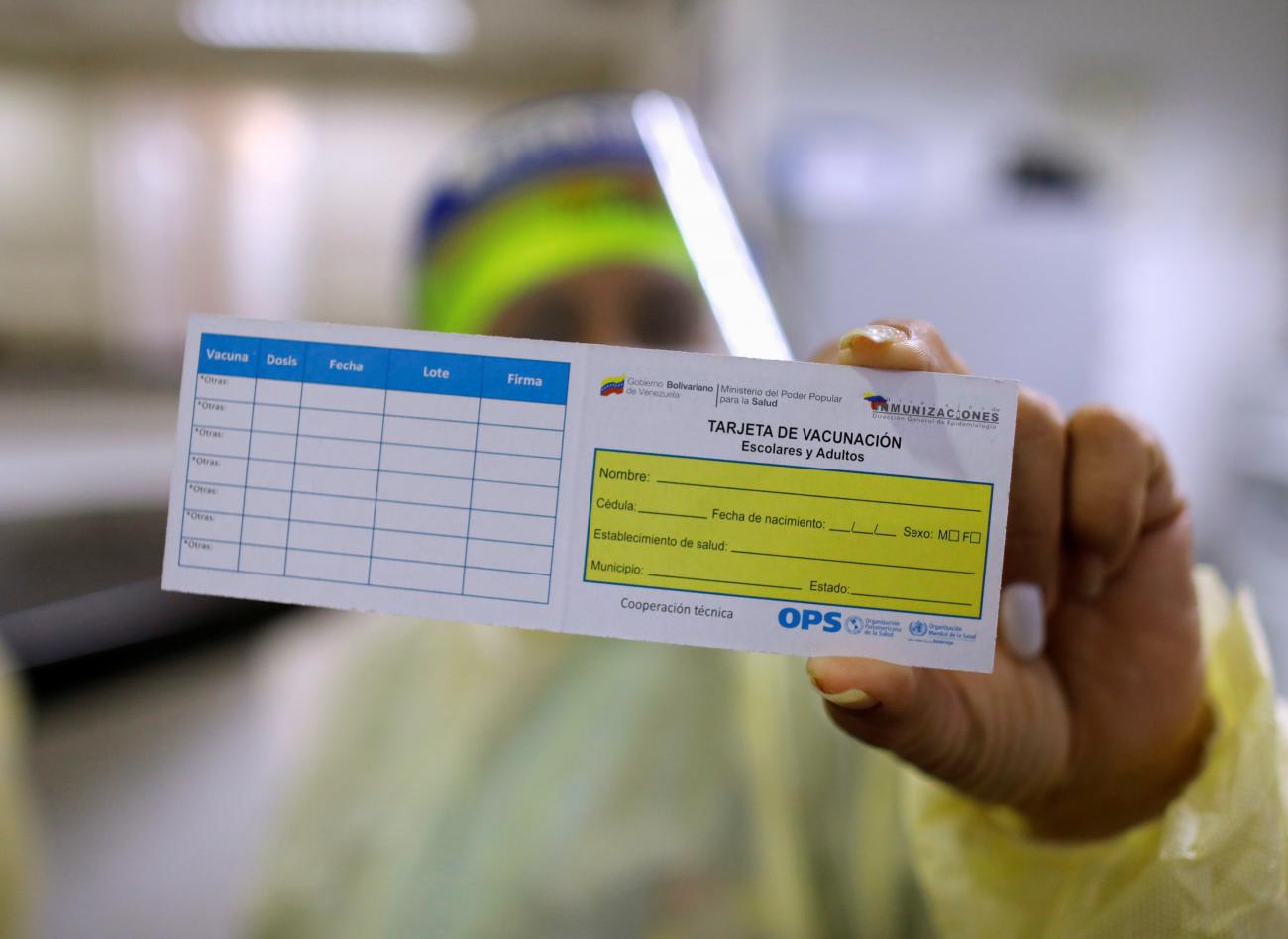

Whether a physical credential or a digital one presented via a mobile application, proof of vaccine status will need to be marketed creatively. Unfortunately, the terms "vaccine passports" and "health passes" have already been severely politicized and misused — predictably so, since these terms can be perceived as governmental overreach. Instead, these services should be promoted as tools of "vaccine verification" that enable a return to normalcy and prevent the spread of the infection. There is evidence for this language modification: in a recent survey conducted by the de Beaumont Foundation, 40 percent of respondents said they were more likely to get the vaccine if the term "verification" was used for vaccine confirmation, followed in preference by the term "certificate" (22 percent).

Similar tools are already in broad use. The World Health Organization has long required proof of vaccination against Yellow Fever for international travel, and public schools in the United States have mandated vaccines against polio and measles. Since last year, various organizations and services—including airlines—have required customers to produce COVID-19 test results to enable access. Given the safety concerns around the spread of infections, most people intuitively understand why these policies make sense and would not label them as un-American.

Insights from behavioral economics can guide development of means for verifying vaccination status. Getting vaccines should be framed as doing something for the benefit of broader society, as behavioral economics research shows people are more likely to participate in an activity when they see certain actions as a public good. To the greatest extent possible, people should voluntarily self-disclose their vaccine status rather than be required to do so. Vaccine delivery programs (such as mass vaccination sites) should encourage—not mandate—people to display their vaccine status, similar to how voting stickers are used.

Getting vaccines should be framed as doing something for the benefit of broader society

Targeted marketing can also be developed using behavioral economics, such as highlighting stories of people who had a recent positive experience with the COVID vaccination to take advantage of the availability heuristic, a cognitive bias where people overestimate the likelihood of an event when they can vividly recall an example of the event. Messaging techniques could also be reframed to underscore the increased risk of contracting and spreading the coronavirus infection for those who avoid vaccination, applying the principle of loss aversion, another cognitive bias where people show increased reluctance to suffering a loss compared to a gain of similar value.

Vaccine delivery programs must also be explicit about incorporating equity as a goal. As highlighted by our research, it is not enough to improve access to health-care innovations: delivery programs must place increased focus on communities who are at higher risk. The ongoing pandemic has already revealed the disproportionate burden of COVID-19-related deaths on underserved and historically marginalized communities. As access to the vaccine improves, delivery programs need to develop mechanisms to prioritize those at higher-risk of contracting the infection. Emphasizing equity as a goal will send a strong signal to underserved communities that their concerns are being taken seriously, which in turn will enhance the trust in vaccination campaigns. COVID-19 is a reminder that none of us are safe until all of us are safe.

Lastly, people should also be assured that vaccine verification solutions will not be used against them in any way. It was a positive step when earlier this month the White House announced that the federal government would not issue, track, or store, the information related to an individual's vaccine status. At the same time, there are real threats to securing herd immunity against the virus, particularly misinformation about vaccines and longstanding mistrust in the health-care organizations. According to a recent poll, 25 percent of Americans would refuse to get vaccinated, and another 5 percent are unsure.

COVID-19 is crushing health systems in Brazil, India, and Europe. Countries like France and Canada have reinstated strict lockdowns. Vaccines provide the safest method to avoid these setbacks. In the United States, policymakers should learn from past mistakes and exhibit thoughtful leadership. With viral variants threatening to extend the pandemic, efforts at the community level—such as masking, physical distancing, hygiene, and now vaccinations—continue to be the core practices in curbing their spread. Vaccine verification solutions will augment these efforts.