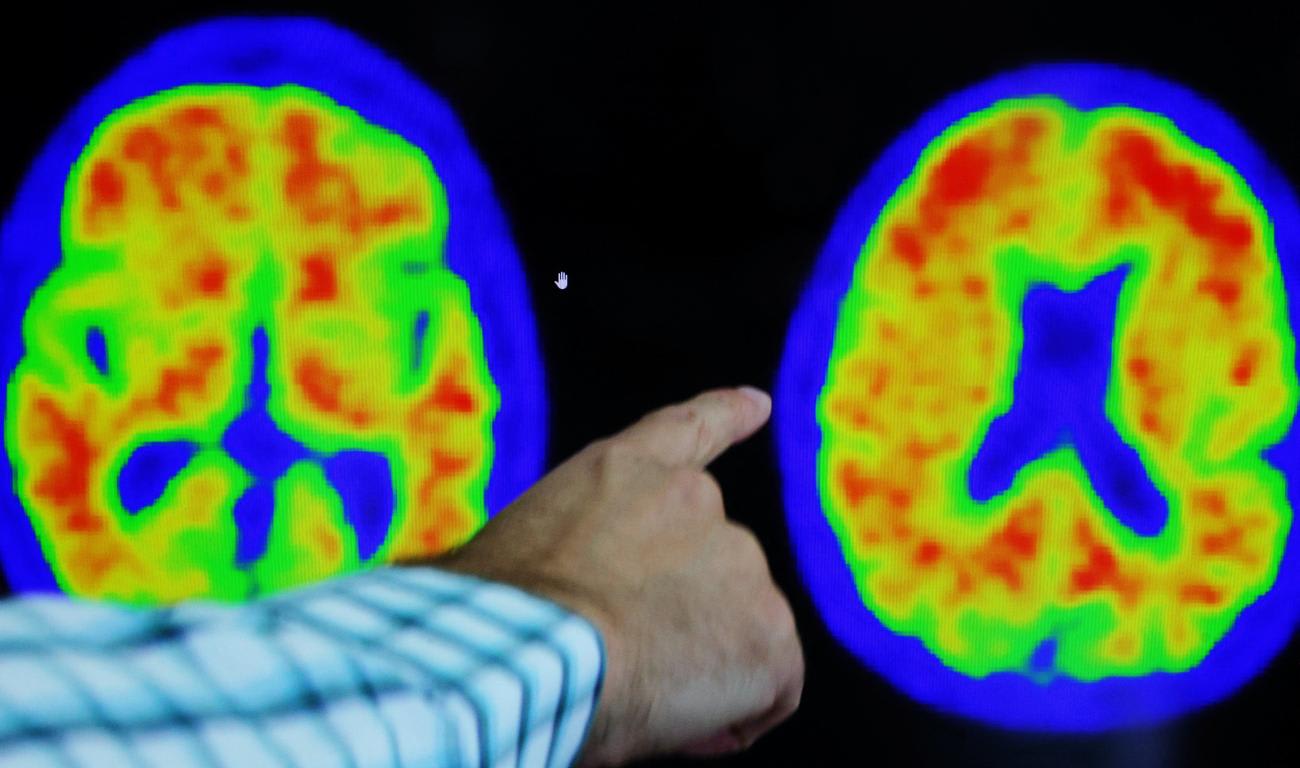

On July 6, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration granted full approval to Leqembi, a promising new therapy clinically proven to slow cognitive decline in people living with early-stage Alzheimer's disease. On the same day, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services pledged to cover the drug's cost, paving the way for people to gain access to the treatment.

This was momentous for the Alzheimer's community, providing hope to millions of people who could benefit from the treatment. The medicine holds the promise of delaying disease progression by one to two years, which will provide meaningful additional time with family and friends and enable longer independence while lowering caregiving expenses and reducing time spent in nursing homes.

But will the arrival of this treatment mark a turning point in the battle against Alzheimer's? Or will the potential fade as the grim toll of the disease continues to mount?

The answer depends on whether governments across the globe step up to match the scientific and medical progress by marshaling a fully coordinated, adequately funded effort on the scale needed to address this escalating challenge, one driven inexorably by the aging of the world's population.

Fifty-five million people already live with Alzheimer's, and population aging means ten million new cases annually

Even before Leqembi won FDA support, European news reports raised questions about the impact new Alzheimer's treatments will have on government health-care budgets, and experts suggested that high prices would likely restrict their use. These concerns are understandable but shortsighted. It's time to start fully weighing the cost — financial, human, and societal — of a world without new treatments, where hope of altering the course of the disease is minimal at best.

Fifty-five million people already live with Alzheimer's, and population aging means ten million new cases annually. Without a robust portfolio of disease-altering therapies, vastly improved testing and diagnosis, and widespread adoption of prevention behaviors, a projected 139 million people will be living with Alzheimer's by 2050.

Today, it is wealthy nations like Japan, Italy, and Finland where large shares of of the population are older than sixty-five and therefore at risk. But the World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that by 2050, about 80 percent of the world's older people will be living in low- and middle-income countries. A study in The Lancet projects that dementia cases will rise by 367 percent in North Africa and the Middle East and by 357 percent in sub-Saharan Africa by mid-century.

The coming wave of people suffering from Alzheimer's will not simply bankrupt millions of individuals and families. It will also imperil government health-care budgets around the world.

In the United States, average Medicare spending on someone with Alzheimer's is nearly three times higher than spending on other seniors. In fact, in 2023, Medicare and Medicaid will spend $222 billion to provide care to people with Alzheimer's and other dementias, according to the Alzheimer's Association. That's nearly triple what the federal government spent on education ($76.4 billion) and exceeds the $184 billion paid to all U.S. military personnel. By 2050, this Medicare spending is projected to hit $1 trillion.

These figures don't even include the indirect, society-wide costs of Alzheimer's — the loss in productivity and diminished quality of life of family members turned unpaid caregivers. In 2022, more than eleven million family members and friends provided eighteen billion hours of caregiving, valued at $340 billion.

Globally, estimates from 2018 pegged the economic burden of Alzheimer's at $1.1 trillion per year, a figure that will double by 2030.

Unlike COVID-19, which emerged abruptly, the coming Alzheimer's crisis is entirely foreseeable. There's no excuse for inaction. Yet the WHO found that only one-quarter of the world's countries have a national policy, strategy, or plan to support people with dementia.

A 2021 analysis by the International Monetary Fund found "global investment in [Alzheimer's] treatment, supportive care, and prevention is seriously lacking" relative to other diseases. The authors concluded that "dementia is an economic nightmare about to metastasize as the world, especially poorer countries, experiences unprecedented population aging."

Although U.S. funding for Alzheimer's research has increased, that of other countries has been slow to follow.

The United Kingdom invests five times more in cancer research than it does in dementia. Despite its rapidly aging population, Japan devotes just 0.2 percent of its research funding to dementia. The Canadian Institutes of Health Research spent a grand total of $49 million (Canadian) on dementia research in 2020 and 2021.

Average Medicare spending on someone with Alzheimer's is nearly three times higher than spending on other seniors

The time is long overdue for governments worldwide to respond to — and budget for — Alzheimer's as the serious public health crisis that it is. In the face of government complacency, international coalitions are forming to spur action and make needed investments.

At the 2020 World Economic Forum, a diverse group of private-sector executives, government leaders, and nongovernmental organizations came together behind a singular goal: to mount a global response to Alzheimer's by driving solutions that will end the suffering and ease the financial burden of the disease.

The result was the launch of the Davos Alzheimer's Collaborative, which is based on the idea that an international partnership is the best approach to accelerating innovation, preparing health-care systems to deliver emerging treatments, and ensuring that solutions work equitably for people worldwide.

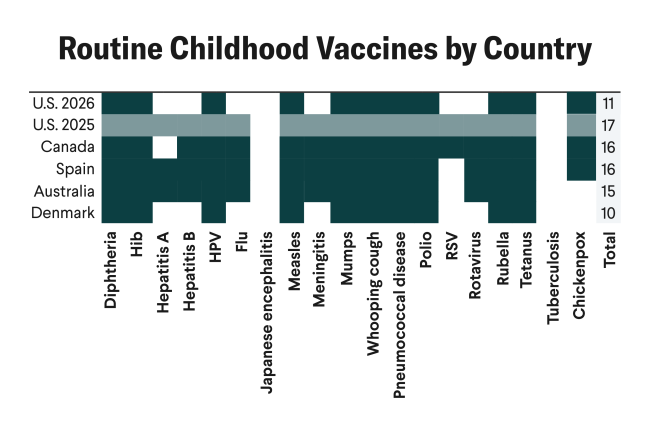

The collaborative follows the public-private partnership model pioneered by successful international efforts such as Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, which has helped vaccinate more than 981 million children in the world's poorest countries, and the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations, which promotes the development of vaccines against emerging infectious diseases and ensures equitable access to these treatments.

Why is an international approach to Alzheimer's so critical? For starters, scientists don't have a clear picture of how Alzheimer's affects diverse populations. Today, 90 percent of the genetic information about Alzheimer's comes from white populations of Western European origin. This severely limits the ability to close the equity gap, understand the full complexities of the disease, and develop treatments that can work for all people worldwide.

For decades, scientists, disease advocates, health-care agencies and countless individuals have fought, largely unsuccessfully, to change the rising trajectory of Alzheimer's. Science has cracked open the door to slowing the disease's progression. Governments worldwide should embrace this opportunity by increasing investments in research, preparing their health-care systems to deliver coming treatments, and galvanizing international cooperation to end the vast human suffering and soaring financial toll of Alzheimer's.