Imagine sitting in close quarters with COVID-19 patients in the poorly ventilated interior of an ambulance multiple times a day. Now imagine transporting those patients to a hospital where all the staff have been vaccinated against COVID-19, but you have not. That is the situation that many emergency responders in my state find themselves in today.

As an emergency physician, I was elated to be among the first to get the vaccine. But after a joyful tide of vaccine selfies that seemed to lift the collective burden on all our shoulders, I am left with the empty feeling that others, perhaps facing even higher risks than me, are falling through the cracks.

And if states can't even ensure vaccines are distributed to health-care providers in a coordinated, fair fashion, how will they do this for the general public? My colleagues and I are worried that the United States' uncoordinated and fragmented response to the pandemic will continue to manifest itself, resulting in chaotic and inequitable distribution of the vaccines.

If states can't ensure vaccines are distributed to health-care providers in a coordinated, fair fashion, how will they do this for the general public?

On December 11, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommended that the highest-risk providers should be vaccinated first, but each state, hospital system, and county seems to have its own method of deciding who gets prioritized. My hospital system vaccinated providers in order of occupational risk, but another area hospital with different guidelines disregarded clinicians' specialties in doling out the vaccine. Surgeons there who perform only elective procedures on patients who have tested negative for COVID-19, and radiologists who don't see patients face to face at all, were vaccinated on the same day as emergency physicians and nurses who see COVID-19 patients every day.

In many places, hospital-based specialties were prioritized ahead of primary care providers despite the fact that the latter group might actually have the highest risk of dying of COVID-19. A friend who is a family physician in the Midwest, incensed that radiologists were being vaccinated before her, showed up and requested a vaccine even though it was not yet her turn—and received one. But some of her older, more vulnerable colleagues are still waiting for theirs. (And although her actions seem justified to me, her ability to skip the line is itself a cause for concern).

Regardless of exact order, most health-care providers will be vaccinated within weeks — but the inconsistent approach and the fact that it was left to each health system or county to figure out how best to vaccinate its providers does not bode well for a rollout to the public.

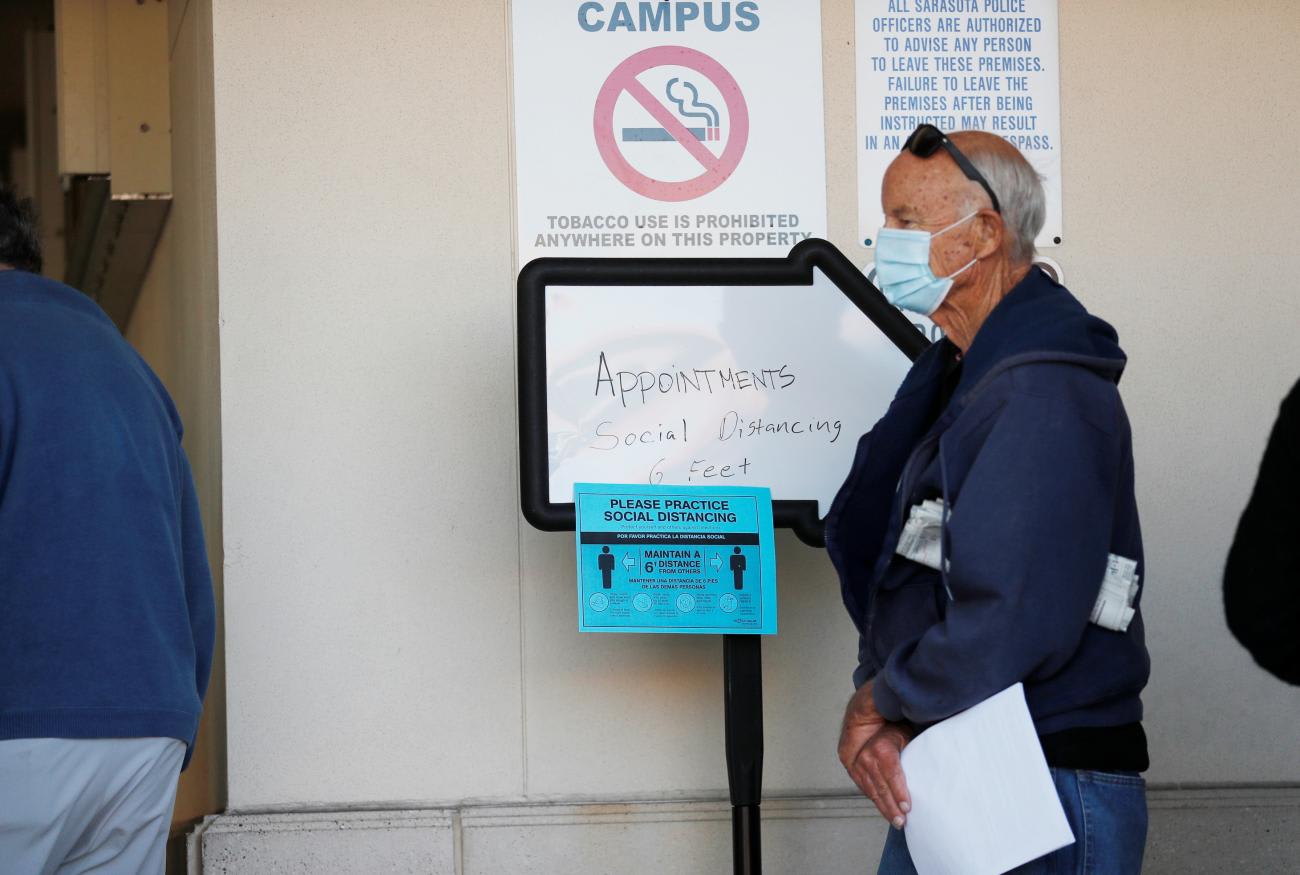

States are taking entirely different approaches. For example, my 70-something parents who live in Virginia have received no information on how and when they will be vaccinated, but the Florida health department is asking those over age 65 to register to receive it.

At the same time, the CDC's recommendations for vaccinating the public leave plenty of ambiguity. They prioritize risk factors as broad as obesity, which afflicts 40 percent of the population, and smoking, a behavior practiced by 14 percent of Americans. But how will people be sub-prioritized within those groups? Will a 23 year-old who has smoked for three years be in line before a 63 year-old with no unhealthy habits and no medical problems or other risk factors?

How will the vaccine be rolled out to vulnerable populations? Many of my patients in the emergency department are the working poor, the homeless, non-English-speaking migrants, or otherwise marginalized by the system. These groups work jobs that preclude them from getting vaccinated at health departments that are only open nine to five. They don't have primary care providers to give it to them. They mistrust the system in general and vaccines in particular — and get the vaccine at lower rates than average. They will find getting in line for a COVID-19 vaccine challenging—if they can even find someone to give it to them.

Private pharmacies are being enlisted to help with vaccinating elderly patients in long term care facilities and certainly could be a valuable resource in the general rollout—but there are many parts of the country that are pharmacy deserts, populated by people who may need vaccine the most.

The world watched with dismay and horror as the United States, a scientific leader, botched its response to the pandemic. Now that U.S. companies are producing two of the first proven vaccines, there is a chance to demonstrate that we can once again be ascendant when it comes to science. But if we don't vaccinate our population with care and coordination, we will lose any credibility we have regained. This calls not for a one-size-fits-all plan that each state is mandated to follow, but a granular, thoughtful assessment of risk with a specific plan for vaccinating each hard-to-reach group.

There is a chance to demonstrate that the United States can once again be ascendant when it comes to science

For example, vaccinating a mostly rural county in Alaska will be vastly different from vaccinating an inner-city Chicago neighborhood. Each state faces its own mix of challenges, but there are solutions that can be applied regardless of which state is employing them. Even though there are testing sites in the community that are free of charge, many migrant workers come to my emergency room to get tested. If they see the ER as their only avenue of receiving medical care, it makes sense to universally offer COVID-19 vaccines in this setting, as some ERs do with the flu vaccine.

A thoughtful plan will optimize the speed and efficiency with which states distribute the vaccine. Given that so far only a fraction of the doses supplied by Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna have been used, there is still a long way to go. It would be tragic if what delayed the end of the pandemic was not the manufacturing of vaccine but our ability to distribute it as quickly as possible.

Moreover, we must also turn our attention to assisting other countries, recognizing that COVID-19 is a global problem and no country can remain safe without a global solution. In addition to leading in the vaccination of our own population, we have the opportunity to assist others in doing so as well, and perhaps to redeem ourselves a bit in the process.